EU Digital Regulation Simplification and Europe’s Missing Tech Decade

Input

Modified

EU digital regulation simplification will shape Europe’s tech power Fragmented rules now act as an uncertainty tax on digital innovators The article urges clear, one-stop rules that turn high standards into an advantage.

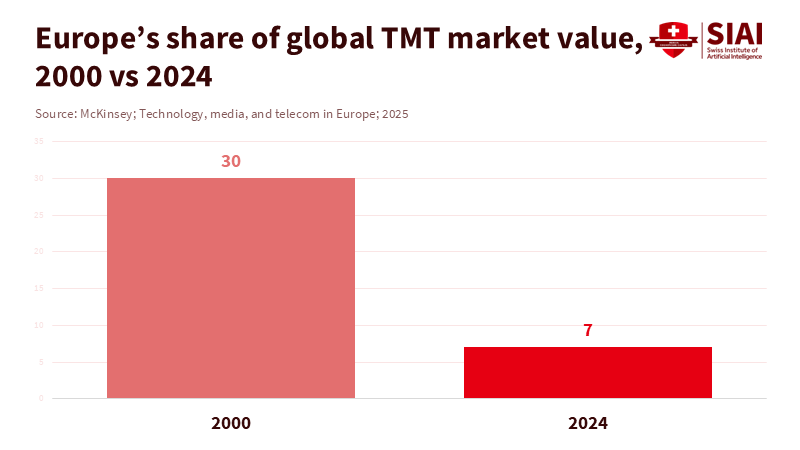

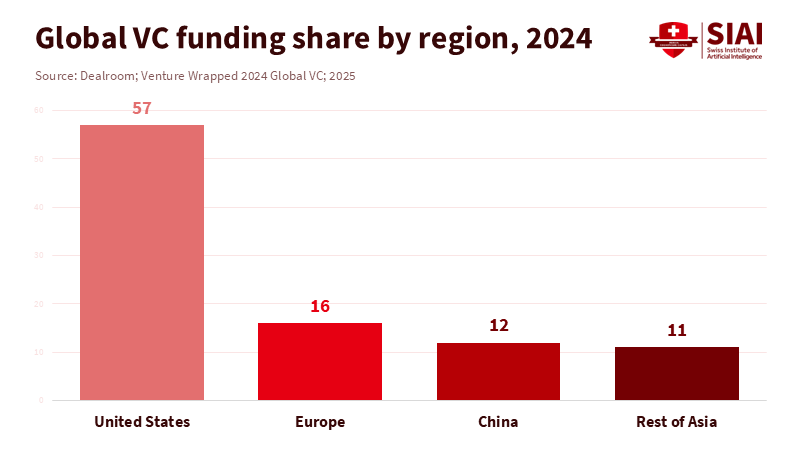

The most significant number in Europe’s digital narrative isn’t about regulation. It reflects the drop in Europe’s share of the global technology, media, and telecom market value, from about 30% in 2000 to roughly 7% in 2024. This represents an $8 trillion “missed opportunity” if Europe had maintained its position. During this time, the EU established a comprehensive digital rulebook, including the GDPR, the Digital Services Act, the Digital Markets Act, and, most recently, the AI Act. In 2024, Europe’s startups still secured around 16% of global venture capital. However, by early 2025, that share fell to about 11% as US and Asian tech hubs advanced. Europe has a wealth of engineers and ideas, but it lacks scale. Now, the EU emphasizes digital regulation simplification with the “Digital Omnibus” package, which aims to streamline key laws. The question remains: will this change spark a decade of growth, or will it cement Europe’s position as a permanent second-tier player?

The stakes are very real. Europe’s rules were designed to protect privacy, limit platform power, and keep AI compliant with fundamental rights. These goals remain essential. However, the rules now rely on 27 legal systems and several regulators, while capital markets still lag behind competitors. The outcome is a continent that bears the burden of being a regulatory superpower while struggling to grow its own global tech companies. In this context, EU digital regulation simplification is viewed not as mere bureaucratic tidying up but as an essential element of industrial policy. Suppose simplification does not become sharper and quicker, focused on helping firms scale across the single market. In that case, Europe’s next generation of digital companies, including EdTech, online universities, and skills platforms, may start here, comply with European rules, and then export their value elsewhere.

EU digital regulation simplification as industrial policy

The new simplification effort is often seen as a neutral cleanup. This is not the case. The Digital Omnibus package would establish a single incident-reporting channel for cyber and data breaches, combine redundant data-sharing laws into a stronger Data Act, adjust GDPR to make it easier to train AI models using European data, and reduce cookie banners that complicate browsing sessions. It would also postpone or revise some high-risk AI requirements, giving regulators and firms more time to prepare. Supporters view this as necessary realism, acknowledging that excessive compliance costs hinder competitiveness. Critics, including civil society organizations and some academics, argue that “simplification” has become a cover for deregulation, driven by large tech companies and foreign governments concerned about strict European standards. Both sides may overlook the crucial point: digital regulation now involves more than just rights and risks; it dictates the fundamental structure of Europe’s digital economy.

When viewed this way, EU digital regulation simplification becomes a key tool of industrial policy. Europe possesses the assets for success. The State of European Tech reports highlight a tech workforce of around 3.5 million and an ecosystem valued at nearly $4 trillion. Europe has also surpassed 400 unicorns, with new billion-dollar companies emerging each year in software, fintech, climate tech, and AI. However, the Draghi report on competitiveness reveals a stark reality: between 2008 and 2021, nearly 30% of Europe's unicorns relocated their headquarters, usually to the US, while retaining significant engineering teams in Europe. Europe trains engineers and creates the rules, yet often sees the most valuable growth occur outside its jurisdiction. Simplification that shortens market entry, reduces duplicate audits, and stabilizes cross-border compliance will not ensure the next wave of AI or EdTech giants stays European. Without it, moving abroad becomes a sensible choice once a firm exceeds its initial home market.

Why EU digital regulation simplification now defines competitiveness

Europe’s main innovation challenge is no longer the number of laws. It is fragmentation and credibility. Digital experts describe the EU framework as a patchwork: GDPR, the DSA, the DMA, the Data Act, NIS2, and sector-specific rules, each with unique enforcement bodies, timelines, and guidance. National regulators interpret the same EU provisions differently, and their staffing and expertise vary greatly. A large cloud or platform company can treat this as just part of doing business, spreading lawyers across jurisdictions and passing the costs along. For a mid-sized EdTech platform or AI startup, it feels like trying to navigate 27 markets while paying for just one. In this situation, competitiveness depends less on the abstract “burden” of regulation and more on a founder's ability to find a clear path from prototype to scale without years of legal confusion.

The Commission’s focus on competitiveness highlights why this is important. The Draghi report points out that much of the EU-US productivity gap arises from poorer performance in digital-intensive sectors and large-scale platforms. McKinsey’s analysis of TMT companies reflects this in one figure: while global TMT market capitalization rose from about $7 trillion in 2000 to $34 trillion in 2024, Europe’s share fell from 30% to 7%, suggesting nearly $8 trillion in lost value had Europe maintained its pace. Similarly, Dealroom’s global VC data indicates that Europe captured about 16% of global venture capital in 2024, leading China. Still, that share fell to around 11% by early 2025 as US deal flow surged. Europe continues to announce new AI and deep-tech initiatives, yet capital markets and enforcement structures have fallen behind. Thus, EU digital regulation simplification is not a mere philosophical debate about whether to have “more or less” regulation. It is an effort to bridge the credibility gap between ambitious rulemaking and the actual conditions for creating globally scaled firms.

In education systems, this gap affects daily decisions. Public buyers are instructed to use tools that comply with all relevant EU and national rules, even when the guidance is unclear or inconsistent. Ministries hesitate to endorse innovative platforms for remote learning, exams, or skills assessment because they cannot envision how future AI obligations will categorize these tools. Universities and school networks conduct pilots that never expand. This happens not due to technological failure but because no one is clear on what cross-border deployment requires. A genuine round of EU digital regulation simplification would not eliminate safeguards. It would clarify responsibilities, unify core obligations for small providers, and establish stable timelines. This would lower the “uncertainty tax” on adopting reliable digital tools and lessen the inclination to revert to a few global platforms that have already integrated compliance costs into their budgets.

The competitiveness cost of regulatory complexity

It is tempting to view red tape as a cultural aspect of Europe—annoying but manageable—the data point to a sharper reality. The decline in Europe’s share of the global TMT market value from 30% to 7% represents an $8 trillion missed opportunity. Draghi’s competitiveness findings reveal that nearly a third of European-born unicorns moved their headquarters abroad, primarily to the US. Atomico’s analyses and follow-up studies offer additional insight: despite the value of Europe’s tech ecosystem rising to about $3-4 trillion, approximately one-sixth of the value generated by European startups dissipates when they relocate. Pension funds and institutional investors still assign only a tiny fraction of assets to venture capital. None of these issues can be blamed solely on regulation. However, to insist that complex, overlapping rules are inconsequential overlooks how they interact with shallow capital markets, cautious financial practices, and an incomplete capital markets union. Fragmented compliance heightens these challenges, particularly as firms attempt to scale and cross borders.

The EU’s experience in semiconductors serves as a warning. The European Chips Act set an ambitious goal of attaining a 20% share of global chip production by 2030, supported by tens of billions in planned investments. Yet the European Court of Auditors has labeled the strategy as “deeply disconnected from reality,” citing fragmented spending, unclear funding channels, and a gap between political ambitions and industrial capability. The takeaway is not that strategy lacks value; rather, lofty goals without practical implementation and clear rules do not drive market change. In digital regulation, the risk is similar. Europe can announce ever more initiatives to support AI, cloud, and data spaces. However, if each new measure imposes another layer of obligations, another reporting requirement, or another regulator with overlapping authority, then every extra euro of public or private investment yields less effect. For Europe’s digital education sector, this means that generous innovation grants may still lead to marginal results if the underlying rules remain unclear.

Critics of simplification are concerned that this argument will be misused to weaken essential protections. This concern is valid. Europe’s high standards for data protection and algorithmic accountability are not liabilities; they are assets, especially in areas like education, health, and work, where trust is fragile. Parents and students are more inclined to accept AI-supported tools when they know that solid rules are in place and being enforced. The real cost to competitiveness lies not in maintaining strong rules but in piling them on without coordination. Oversight becomes sparse, and pathways to compliance become hard to discern. In this context, EU digital regulation simplification should not be about diminishing rights. It should focus on reducing duplicate reporting, consolidating supervisory roles, and clarifying basic definitions, making essential protections easier to apply, explain, and enforce.

What real EU digital regulation simplification would look like

For simplification to make a difference, it must transform everyday choices for founders, investors, and public buyers. For a startup, this means having a clear overview of which digital rules apply to a product on a single page, instead of piecing them together from national guidelines, sector codes, and informal advice. It means being able to file a breach report once through a real one-stop interface rather than sending variations to multiple authorities. For a small education platform, it means having a clear, reasonable set of requirements for low-risk AI uses—such as content recommendations, adaptive testing, or simple learning analytics—rather than treating every algorithm like a facial recognition system. For universities and international consortia, it means having standardized contractual clauses and straightforward guidance that enable the sharing of anonymized learner data for evaluation and improvement without prolonged uncertainty.

The tools are available. The Digital Omnibus could establish a “once-only” principle for digital compliance, allowing information provided under one law to count toward compliance with others. It could empower the European Data Protection Board and new AI governance bodies to provide joint guidance on issues such as model training, risk classification, and anonymization, rather than leaving companies to piece together separate opinions. It could direct part of the EU’s broader innovation efforts toward shared compliance infrastructure, including open-source toolkits, standardized risk templates, and advisory hubs for SMEs and public bodies. It could also create clearer, well-defined regulations for sectors like education and health, where trustworthy AI needs explicit room for experimentation, coupled with strong prohibitions against high-risk surveillance, manipulation, and abusive profiling. None of this requires lowering standards; it demands treating clarity and enforceability as public goods in their own right.

Educators and administrators should not leave this agenda solely in the hands of lobbyists and specialist lawyers. How EU digital regulation simplification is structured will determine which tools teachers can use in the classroom, how universities conduct high-stakes online exams, and how public employment services deliver large-scale reskilling. Education ministries can require that platforms funded by public funds operate on infrastructure that complies with European law. They can also urge Brussels and national regulators to create simple, stable frameworks for cross-border deployment. School and university leaders can join together to advocate for safe harbor provisions and clear standards for low-risk educational uses of data, rather than passively allowing dependence on a few dominant non-European platforms. By making their needs clear, the education sector can help guide simplification away from a narrow focus on large tech companies and steer it toward the broader ecosystem that truly fosters learning and skills. Europe has already experienced the consequences of ambition and strategy drifting apart. In important digital markets, the EU has set ambitious targets and complicated frameworks. However, it was later realized that fragmented implementation and cautious investment allowed faster rivals to pull ahead—digital education risks following the same path. Schools and universities depend on global platforms with business models and data practices determined elsewhere. Meanwhile, local alternatives struggle to grow amid a maze of rules.

The same studies that highlight Europe’s declining share of global tech value also indicate that with the right mix of investment and reform, the continent could close much of the gap in the next decade. Political leaders are aware of this. The increase in national deep-tech programs and EU-level initiatives shows they understand the stakes. But investment without clarity won’t buy time. To make this effort worthwhile, regulators and lawmakers need to view the simplification of EU digital regulation as a key tool for competitiveness, not just a weary concession to lobbying fatigue. If they can uphold high standards for data and AI while redesigning enforcement and compliance, Europe’s rules could become beneficial for businesses that follow them, rather than a burden on ambition. Then, when we next review Europe’s position in the global tech market, the key figures may finally start to shift in the right direction.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Atomico. (2024). State of European Tech 2024: A decade of growth and resilience.

Dealroom.co. (2025). Venture Wrapped 2024: Global VC report.

European Commission. (2024). The future of European competitiveness — A competitiveness strategy for Europe.

Houston, L., & Burns, C. (2025). Breaking: EU announces major digital and data simplification package and delay to AI Act. Slaughter and May, The Lens.

Jahangir, R. (2025). What’s Behind Europe’s Push to “Simplify” Tech Regulation? Tech Policy Press.

McKinsey & Company. (2025). Technology, media, and telecom in Europe: The new growth engine or another decade of missing out?

O’Carroll, L. (2025). EU microchip strategy “deeply disconnected from reality”, say official auditors. The Guardian.

Times of London. (2025). European tech growth “hampered by red tape”.

Comment