The H-1B Talent Pipeline Is Breaking Before Our Eyes

Input

Modified

The US relies on an H-1B talent pipeline its schools cannot replace New H-1B fees push global talent toward rival countries building strong education–innovation systems Without opening visas and fixing public education, the US will lose its tech edge

In 2024, around half a million skilled workers in the United States held H-1B visas. They filled roles in cloud computing labs, chip design firms, and even rural hospitals that struggle to recruit staff. Most of these workers came from just two countries. About 71% were born in India, and about 12% were born in China. They mainly work in computer and engineering roles with six-figure salaries. This year, the United States announced a one-time application fee of US$100,000 for every new entrant to the H-1B talent pipeline. This fee is almost the same as the median starting salary for new H-1B workers, effectively creating a 100 percent entry tax on global graduates who have supported American innovation for three decades. This move highlights a deeper issue. The country is shutting the door on imported talent, while its education system, especially public schools, is not producing enough world-class STEM graduates to replace them.

A broken H-1B talent pipeline begins in U.S. classrooms

The H-1B talent pipeline has always relied on skills that the United States has not developed fast enough at home. In fiscal year 2024, the country approved about 399,000 H-1B petitions. Indian nationals comprised around 71 percent of successful applicants, while China accounted for another 11.7 percent. These workers are not just entry-level hires. Recent USCIS data indicate that nearly two-thirds of approved H-1B beneficiaries now hold a master’s degree or higher, a significant increase from two decades ago. They are concentrated in advanced roles in artificial intelligence, data science, and complex software engineering, where most H-1B workers are classified in “computer-related” occupations. Behind those visas lies an educational chain that starts in Asian high schools, moves through elite universities in Bengaluru, Delhi, Shanghai, and Beijing, and often finishes with U.S. graduate degrees before returning to American labs and start-ups. The new fee targets the final step in this process, but does nothing to fix the weak foundations of math and science education in U.S. public schools.

Recent results from international and national assessments show how weak those foundations have become. In the OECD’s 2022 PISA tests, U.S. 15-year-olds scored 465 points in mathematics, below the OECD average of 472, and only slightly above average in science and reading, with slight improvement since 2018. By the end of high school, the situation is worse. A 2024 report from the National Assessment of Educational Progress found that over 30 percent of U.S. twelfth-graders lack basic reading skills, while about 45 percent do not reach basic proficiency in mathematics. This represents the weakest performance in over three decades. These scores do not reflect a system prepared to replace hundreds of thousands of foreign engineers, coders, and data scientists in the coming decade. Instead, they signal a system that has quietly outsourced its top STEM talent to the H-1B talent pipeline.

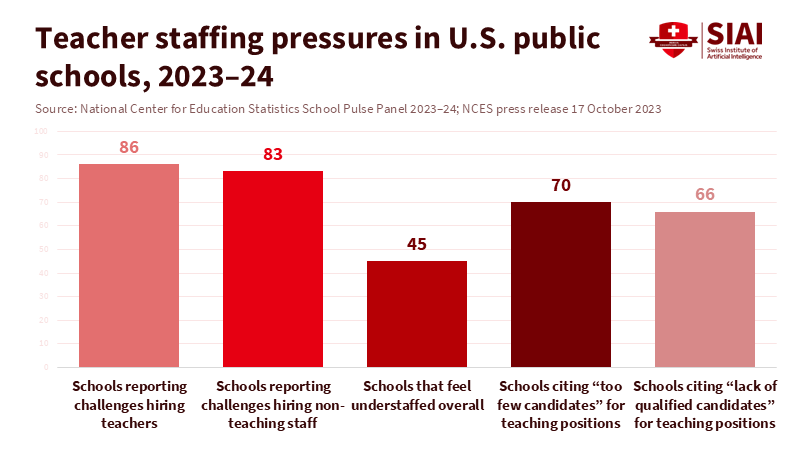

The erosion starts with people, not curricula. U.S. federal statistics show that 86 percent of public schools reported severe difficulties hiring teachers during the 2023–24 school year, mainly due to a shortage of qualified candidates. More than 40% of schools have had to employ underqualified teachers. Nearly 30% of classes had increased class sizes, and a quarter cut course offerings to manage staff shortages. STEM subjects have been hit hardest. An analysis of federal and state data for 2022–23 revealed shortages of mathematics teachers in 31 states and science teachers in 34. At the same time, teachers earn about 26.6 percent less than other workers with similar levels of education. An estimated 300,000 teachers and school staff left the profession between early 2020 and mid-2022. This is what a collapsing domestic H-1B talent pipeline looks like long before a visa officer sees an application form.

The global race to reshape the H-1B talent pipeline

Other countries observe these trends and see an opportunity. When Washington raised H-1B application fees to as much as US$100,000, governments in Canada, Germany, and China quickly positioned themselves as friendlier options for global graduates and mid-career engineers. Their policies are concrete. Many now offer multi-year post-study work visas, points-based routes to permanent residency, and streamlined paths from student status to skilled migration. Across the OECD, and increasingly beyond it, international education and skilled migration have merged into a single strategy: attract young talent to universities, help them build careers, and then keep them. American policymakers may view the H-1B talent pipeline as a narrow labor-market tool. Still, competitor countries see the same pool of students and workers as vital to their long-term innovation systems.

India is at the center of this shift. Between October 2022 and September 2023, Indian nationals received over 72 percent of all H-1B visas issued. In fiscal 2024, they still made up about 71 percent of approved beneficiaries. This dominance reflects a generation of engineers who built careers in Silicon Valley before stepping into leadership roles across global tech. Now, Indian policymakers aim to reverse this trend. The country has more than 1,600 global capability centers that employ over 1.6 million professionals, with the market projected to reach up to US$105 billion by 2030. India’s AI mission has allocated over ₹10,300 crore over five years to develop large-scale computing infrastructure, including nearly 19,000 GPUs for research and industry. These investments aim to help highly skilled Indians, including U.S.-trained graduates, build advanced careers without ever entering the H-1B talent pipeline.

India is not alone. Universities in Europe, Australia, and parts of East Asia are rebuilding their graduate pipelines to attract international students who once viewed a U.S. H-1B job as the top prize. Recent data on global student flows reveal that international students contributed approximately US$43.8 billion to the U.S. economy in the 2023–24 academic year and supported over 378,000 jobs. More than 70 percent of these students came from Asia, with nearly half from India and China. Those flows are increasingly contested. Countries that enable graduates to transition smoothly from student status to work visas and maintain predictable fees are capturing a larger share of the same talented young people. Suppose U.S. policy makes the H-1B talent pipeline seem arbitrary, costly, and politically unstable. In that case, many of those students will not even begin their journey in an American classroom.

Rebuilding the H-1B talent pipeline through education reform

In this context, it may be tempting to view the H-1B fee increase as a way to force companies to invest in domestic training. However, this view overlooks the state of the education workforce that would need to carry the load. When almost nine in ten public schools report serious hiring issues and many already rely on underqualified staff, there is no pool of surplus teachers waiting to step up for advanced STEM education. Shortages of mathematics and science teachers exist across most regions of the country, and many experienced educators have already left the profession since the pandemic. With teachers earning over a quarter less than other graduates and facing rising workloads and diminishing professional independence, the incentives point away from the classroom. The H-1B talent pipeline cannot be strengthened by command when the workforce needed to teach the next generation is already in crisis.

Rebuilding that capacity requires policies that view education as essential infrastructure, on par with semiconductors or cloud data centers. A serious plan for the H-1B talent pipeline would combine immigration reform with long-term investments in teachers, not just new facilities or technology. This means raising starting salaries for high-demand subjects, expanding paid residency programs that help new teachers learn on the job, and creating clear career paths that retain skilled educators rather than pushing them into administration or out of schools entirely. It also means connecting high schools, community colleges, and universities with local employers, so students can see how advanced math, coding, and data skills apply to real-world work. When learners experience strong teaching, clear paths, and visible opportunities, the domestic H-1B talent pipeline begins years before a visa application. It becomes much more resilient to political shocks.

Keeping the H-1B talent pipeline open while the system heals

Critics of the program argue that the new fee is a necessary measure to prevent companies from using foreign workers as a cheap alternative to American graduates. However, research presents a more nuanced view. Studies of the 2007 H-1B lottery show that companies awarded extra visas hired more college-educated workers overall, grew faster, and were more likely to survive, with no evidence of displacing native-born graduates. Other studies suggest that increases in high-skilled immigration between 1990 and 2010 contributed to an estimated 30-50% of U.S. productivity growth, partly through innovation spillovers. Data from patents, firm earnings, and city employment all point in the same direction. When managed well, the H-1B talent pipeline tends to complement rather than replace domestic talent, helping to keep advanced industries in the United States rather than relocating entire research teams abroad.

That is why the new US$100,000 fee feels less like a targeted fix and more like an alarm. It taxes future participants in the H-1B pipeline. In contrast, the domestic pipeline is choked with poor outcomes, burnt-out teachers, and shrinking STEM courses, while other countries are racing to make their education systems more attractive to the same students. The path forward is clear. Policymakers can keep the door open to global talent with predictable, clear rules and fees that fund enforcement rather than discouraging participation. Simultaneously, they can treat the teaching workforce and public education as central components of national technology policy rather than afterthoughts. If leaders take action on both fronts, the current fee debate could signal the beginning of a more balanced model in which the H-1B talent pipeline strengthens a robust domestic education system rather than replacing it. If they do not, the next wave of innovative ideas may simply emerge and remain elsewhere.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

American Council on Education. (2022). School staffing shortages: A crisis for teaching and learning.

American Immigration Council. (2024, October 1). The H-1B visa program and its impact on the U.S. economy.

Deccan Herald. (2024, August 27). Global capability centres offering up to 20% higher salaries than IT services: Report.

Drishti IAS. (2024, March 14). Reviving India’s R&D funding.

Economic Policy Institute. (2024, August 15). The teacher pay penalty has hit a new high.

Financial Express. (2025, August 31). U.S. sees 9.5% jump in international student jobs; STEM drives growth.

Mahajan, P., Morales, N., Shih, K., Chen, M., & Brinatti, A. (2024). The impact of immigration on firms and workers: Insights from the H-1B lottery. Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Working Paper 24-04.

National Center for Education Statistics. (2023, October 17). Back-to-school statistics show most U.S. public schools report challenges in hiring teachers.

OECD. (2023). PISA 2022 results: United States – Country note.

Peterson Institute for International Economics. (2025, September 22). New U.S. curb on high-skill immigrant workers ignores evidence it’s likely to backfire.

Reuters. (2024, September 11). India’s global capability centres market to grow to $105 billion by 2030, says Nasscom–Zinnov report.

Reuters. (2025, September 9). U.S. twelfth-graders log lowest reading performance in decades.

Reuters. (2025, September 24). Trump’s H-1B visa fee increase raises U.S. doctor shortage concerns.

Times of India. (2025, September 29). Top 10 countries of birth of approved H-1B beneficiaries in FY 2024; India leading the way.

Washington Post. (2025, September 22). Where H-1B visa holders are from, who hires them and what they earn.

Government of India, Press Information Bureau. (2025, March 7). Cabinet approves IndiaAI Mission with total budgetary outlay of Rs. 10,371.92 crore.

Yadav, S. (2025, February 7). Indian nationals received over 72% of all H-1B visas issued from Oct 2022–Sept 2023. The Economic Times.

Comment