Arctic Sea Lanes and the Russia Factor in US-South Korea Alliance Planning

Input

Modified

Russia–North Korea ties and Arctic shipping are reshaping the US–South Korea alliance The Northern Sea Route turns the Arctic into a new strategic front Education and policy must integrate Arctic routes into Korean security planning

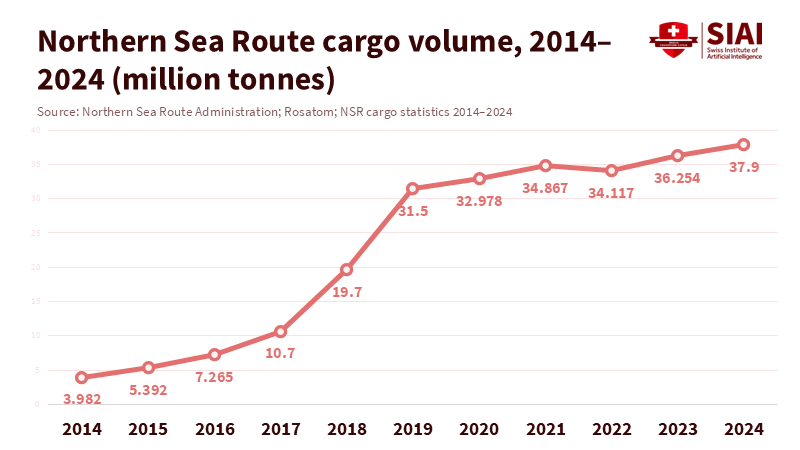

In 2024, the Northern Sea Route (NSR) transported a record 37.9 million tons of cargo, including over 3 million tons moving between Asia and Europe. This occurred while NATO countries increased their defense spending to about 2.6% of their combined GDP in response to Russia’s war in Ukraine. However, discussions about Russia's role in US-South Korea alliance planning often stop at the Demilitarized Zone and the Donbas. They view Russia as a minor player on the peninsula and the Arctic as a distant issue. This perspective is outdated. Russia, which depends on North Korean ammunition and labor for its efforts in Europe and uses Arctic sea lanes to transport energy and goods to Asia, has strong reasons to shift its strategic focus eastward once fighting in Ukraine ceases. For Moscow, North Korea is becoming the critical link between its military operations in Eurasia, its Arctic goals, and its long-term plans in Northeast Asia.

Reframing the Russia Factor in US-South Korea Alliance Planning

From Moscow's perspective, North Korea now has a role similar to Taiwan's in Washington's eyes. Taiwan acts as a strategic asset for the United States, helping it maintain control over access to the Western Pacific. For Russia, North Korea serves as a means to extend its influence in the Korean Peninsula and, by extension, into the broader maritime region of Northeast Asia. This is a practical analogy, not a moral comparison. Since 2024, Russia and North Korea have formalized their relationship through a comprehensive strategic partnership treaty. This treaty includes defense commitments and establishes their cooperation as a long-term alignment rather than a temporary arrangement. This legal framework cements Russia's role in US-South Korea alliance planning for the foreseeable future.

As NATO hardens its position, Russia’s reasons for relying on this new partnership will increase. NATO members have shifted from years of underfunding to a collective defense spending of roughly 2.6% of GDP in 2024. A growing number of members now meet or exceed the 2% target, with discussions underway to raise it to 3.5% or more. A renewed conflict along the Warsaw-to-Kyiv line would bring stronger, better-equipped NATO forces to Russia's western border, yielding minimal benefits for Russia. In contrast, the eastern region offers more opportunities. Here, Russia can leverage its position as a permanent member of the UN Security Council, its emerging military alliance with Pyongyang, and its control over Arctic shipping lanes to influence markets and security rules at a lower cost.

The new Russia–North Korea partnership includes important aspects that US-South Korea alliance planners can no longer ignore. Independent evaluations from Ukrainian, South Korean, and Western intelligence suggest that North Korea has already sent thousands of containers of artillery ammunition and multiple ballistic missiles to Russia. Some estimates indicate that several thousand North Korean workers are currently in Russia supporting operations in Ukraine. In exchange, Pyongyang seems to be receiving food, fuel, cash, and advanced military technology. This exchange allows Russia to maintain its war efforts in Europe without fully mobilizing its own industry and society. It also enhances North Korea’s military capabilities while reducing some of the economic hardship that sanctions aimed to impose. The Russia factor in US-South Korea alliance planning is no longer merely a hypothetical diplomatic concern; it is tied to actual supply chains of shells, missiles, and spare parts.

The Northern Sea Route and a New Eastern Front

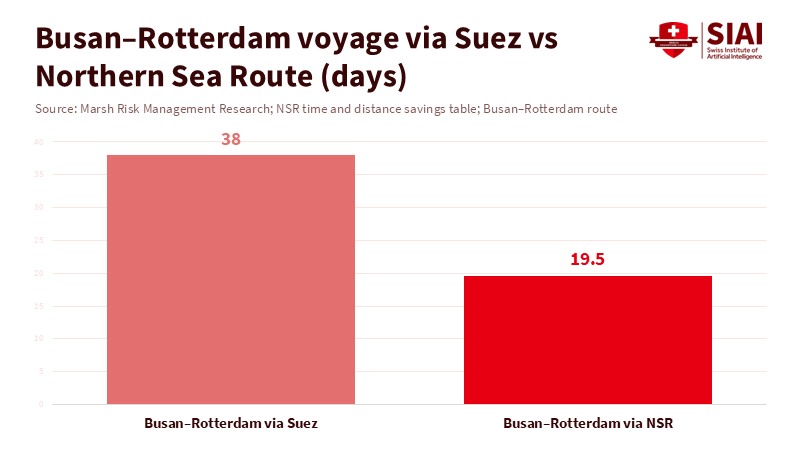

The Northern Sea Route, which runs along Russia’s Arctic coast, can reduce the sailing distance between Northeast Asia and Northern Europe by 20-40% compared to the Suez Canal, depending on the ports involved. On specific routes between Japan and Europe, a journey that takes more than three weeks via the Suez Canal can, under favorable conditions, drop to roughly ten days through the Arctic. This difference results in lower fuel costs, fewer crew days, and less exposure to chokepoints such as the Red Sea and the Strait of Malacca. As climate change reduces summer sea ice and Russia invests in icebreakers, ports, and satellite navigation, this route has transitioned from an experimental idea to a practical corridor. For a Eurasian power constrained by sanctions and seeking new advantages, Arctic geography is a strategic asset.

Traffic statistics along the Northern Sea Route demonstrate how quickly this asset is developing. In 2023, transit traffic reached around 2.1 million tons over 75 voyages, as Chinese and Russian companies moved more cargo through the corridor. In 2024, cargo volume along the route rose to a record 37.9 million tons, with more than 3 million tons transiting on 92 voyages. Trade along the NSR has increased several times since the mid-2010s. Most of the increase has come from Russian liquefied natural gas and Chinese-controlled shipping, but the trend is clear. Despite sanctions, war, and insurance issues, the Northern Sea Route is no longer just an experiment; it is becoming a busy thoroughfare for energy and bulk goods, with Russia controlling access.

South Korea has begun to view this shift as a national priority rather than a distant issue. Busan has created an Arctic Shipping Route Task Force to establish itself as a hub for future NSR traffic. The government has formed a special team in Seoul to coordinate Arctic policy. Plans are underway for pilot operations on Arctic routes starting in 2026, with funding for ice-class vessels, port improvements, and a dedicated Arctic shipping division within the administration. Political leaders have framed this Arctic route as a way to strengthen connections to Europe, secure supply chains, and revive shipbuilding and marine equipment industries in the southern part of the country, promoting Busan as a key logistics center. South Korea is incorporating the Arctic into its economic and industrial plans.

For Russia, this presents both opportunity and risk. On one side, South Korean involvement promises investment, technology, and cargo that can help support Russia’s significant spending on Arctic ports, nuclear icebreakers, and navigation systems. Russian strategy documents already identify the Northern Sea Route as a vital transport corridor and an essential element for economic growth in Siberia and the Far East. On the flip side, if South Korea and other US-aligned nations become prominent users of the NSR, they will prioritize safety standards, environmental regulations, and reliability. This could lead to international norms being applied to what Moscow considers a primarily domestic waterway. How Russia navigates this balance will directly affect the level of trust Seoul and Washington place in the long-term stability of Arctic routes.

This is where North Korea re-enters the equation. For decades, planners and analysts have proposed linking Russian Far Eastern railways and ports to Japanese and South Korean markets via North Korean territory and ports such as Rason. Most of these projects halted due to political issues. However, the new Russia–North Korea defense agreement, combined with Moscow’s focus on Arctic shipping, gives these ideas a fresh perspective. A Russia that needs North Korean labor and reliable routes for transporting goods has every reason to see North Korea as both a buffer and a bridge between its Arctic corridor and the broader Northeast Asian economy. This shift means that the Russia factor in US-South Korea alliance planning is now not just about preventing conflict on the peninsula. It is about whether the allies can influence, or at least prepare for, a network of Arctic-to-Asia routes in which Pyongyang becomes a crucial hub.

Educating for an Arctic Alliance Era

These changes directly affect how we teach and plan around the US-South Korea alliance. Curricula in international relations and security studies still typically center on three main pillars: deterring North Korea, managing China's rise, and sharing defense responsibilities within the US-led framework. Discussions of Russia often take place only in the context of Ukraine or of competition between great powers in Europe. The reality is evolving. The Russia factor in US-South Korea alliance dynamics now includes munitions supply chains, Arctic port development, treaty law, and freedom-of-navigation debates along the Northern Sea Route. Students graduating from policy programs without understanding Arctic shipping economics, Russian Far East demographics, or the specifics of the Russia–North Korea treaty will lack the preparation needed to make the decisions they will soon face.

For alliance planners, the first practical consequence is that strategies must incorporate maritime and Arctic scenarios alongside traditional responses to peninsula crises. Exercises that once focused on defending Seoul or reacting to missile tests now need to include simulations where Russia uses Northern Sea Route access, energy shipments, or cyber actions against port infrastructure to pressure South Korea during a crisis. Effective responses will require cooperation not just among defense ministries, but also among agencies focused on transport, environment, and industry, along with a shared understanding of Arctic developments. The Russia factor in US-South Korea alliance planning now goes beyond joint military drills in Korea; it encompasses joint monitoring of ice conditions, shipping patterns, and networks evading sanctions.

The second consequence is economic and educational. South Korea’s aspirations to become an Arctic shipping center align with its goals to lead in green technology, shipbuilding, and digital logistics. Universities and vocational schools can play a crucial role by developing programs that merge maritime engineering, climate science, and security studies. Joint US-Korean research projects on Arctic governance, environmental protection, and indigenous rights can also bolster the legal and ethical foundations for future shipping. Integrating the Russia factor into US-South Korea alliance thinking in these programs will help ensure that future practitioners view Arctic issues as essential elements of regional security rather than afterthoughts.

Critics may argue that this perspective overemphasizes the Arctic's significance. They might point out that global container shipping through the Northern Sea Route is still small compared to Suez routes, that sanctions and war-related risks could hinder growth for years, and that North Korea remains an unpredictable partner for Russia. These concerns are valid. The NSR will not replace traditional routes overnight. Western carriers remain cautious, and climate fluctuations could introduce new risks. However, strategic changes often begin on the margins. The fact that the route has already seen record cargo volumes, that South Korea is investing political resources and public funds in Arctic initiatives, and that Russia is now committed to a mutual defense agreement with North Korea indicates a lasting structural change, not a temporary trend.

Ultimately, the Russia factor in US-South Korea alliance planning is being reshaped from the ground up. A Russia weary from the war in Ukraine, facing a fortified NATO to its west, and counting on Arctic routes to sustain its economy, will view the Korean Peninsula through a new perspective. North Korea provides Moscow with a steady source of military resources, a legal ally under a mutual defense agreement, and a potential connection between Arctic ports and Northeast Asian markets. Meanwhile, South Korea is looking to the Arctic to secure trading routes and support high-tech industries at home. The challenge for policymakers and educators is whether alliance thinking can adapt quickly enough. If it does, today’s students will learn to recognize Arctic shipping and North Korean-Russian ties as vital components of regional security, not mere afterthoughts. If it does not, the next crisis on the peninsula may come not only in the form of missiles over the sea but also as slow-moving convoys through the polar night.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Al Jazeera (2025) ‘NATO countries’ budgets compared: defence vs healthcare and education’, 25 June.

Arctic Institute (2020) The Future of the Northern Sea Route – A “Golden Waterway” or a Niche Trade Lane?

ArcticToday (2023) ‘China pushes Northern Sea Route transit cargo to new record’, 18 December.

ArcticToday (2025) ‘South Korea launches task force to prepare for Arctic shipping route’, 18 February.

Business Insider (2025) ‘Russia is relying so heavily on North Korea that it’s getting 50% of its ammo from Pyongyang’, February.

Center for High North Logistics (2024) ‘Main results of NSR transit navigation in 2024’, 28 November.

Chatham House – Howell, E. (2024) North Korea and Russia’s Dangerous Partnership.

Congressional Research Service (2025) Russia–North Korea Relations, 13 June.

Diplomat – Panda, A. (2025) ‘The Russia-Ukraine war has made North Korea more dangerous’, 14 August.

East Asia Forum – Rinna, A.V. (2025) ‘The Russia factor in US–South Korea alliance planning’, 22 November.

Guardian (2024) ‘Russia and North Korea sign mutual defence pact’, 19 June.

High North News – Humpert, M. (2025) ‘South Korea to enter Arctic shipping with pilot operations during summer 2026’, 13 August.

High North News – Humpert, M. (2025) ‘South Korea to subsidize construction of ice-class vessels and expand port support for Arctic shipping’, 15 September.

Index1520 (2025) ‘The Northern Sea Route as a key Russian transport corridor: strategic significance and prospects’, 31 March.

Jamestown Foundation – Blagov, S. (2006) ‘Russia, China, Japan and South Korea to launch new sea route linking China and Japan’, Eurasia Daily Monitor, 11 September.

JoongAng Daily (2025) ‘Korea looks to add Arctic shipping routes amid global rush to the North’, 22 September.

Korea Herald (2025) ‘Why Korea is suddenly talking about Arctic shipping route’, 20 July; ‘Why Lee Jae-myung is betting big on Arctic route’, 27 May.

Loadstar – Koo, A. (2025) ‘South Korea breaks the ice with new vision for Arctic box shipping’, 12 August; ‘South Korea races to develop Arctic shipping, revealing plan for “industrial cluster”’, 21 August.

Marineblad (2025) ‘Arctic shipping: the Royal Dutch Navy and the Northern Sea Route’, 6 May.

NATO (2025) ‘Funding NATO’ and ‘Defence expenditures and NATO’s 5% commitment’, official factsheets.

Reuters (2024–2025) coverage of Russia–North Korea mutual defence treaty and KN-23 missile use in Ukraine.

Rosatom / Atommedia (2025) ‘Record volume of cargo shipped along the Northern Sea Route in 2024’, 9 January.

Safety4Sea (2025) ‘South Korea to begin pilot operations on Arctic routes in 2026’, 11 August.

Trans.info (2024) ‘Northern Sea Route: why European carriers are still cautious’, 5 August.

Wikipedia (2024) ‘North Korean–Russian Treaty on Comprehensive Strategic Partnership’.

Comment