Korea Health Income Loss: When Healing Breaks the Paycheck

Input

Modified

Korea’s strong healthcare still leaves families exposed to severe income loss from serious illness Health shocks cut wages, pushing seniors and students into long-term financial strain Korea must pair universal care with robust income protection to prevent poverty after illness

In South Korea, there's a saying about cancer that people share. They often say it’s better to die quickly than to live long enough to bankrupt your family. This might seem harsh, but it comes from real experience. In 2023, around 39.8 percent of Koreans aged 65 and older lived on less than half the national median income, the highest old-age poverty rate among OECD countries. South Korea offers national health insurance to everyone. For many cancers, the formal copayment for insured treatment has dropped to about 5-10%. The clinics operate quickly, and the MRI machines are modern. Despite this, families still worry that a serious diagnosis could ruin them. The main issue isn’t just medical bills; it is Korea's health income loss, the gradual decline in wages that follows a health crisis and pushes households to their limits.

Most discussions about Korean healthcare tend to center on the cost per pill or copayment rates for procedures. This focus is understandable. In the 2000s and 2010s, the government expanded benefits for cancer and other major diseases after realizing that many patients still faced significant medical expenses despite universal coverage. These reforms closed some of the worst gaps, particularly for higher-income patients. However, they left the overall risk structure essentially unchanged. A serious illness remains a medical issue for the insurance fund and a wage issue for the family. As the population ages and jobs become more unstable, this separation isn’t sustainable. If Korea wants a health system that lives up to its global reputation, it must take income seriously alongside health.

Korea's health income loss: the double shock we ignore

On paper, Korea’s health system appears nearly perfect. Every resident is enrolled in national health insurance or a medical aid program. Surveys indicate that almost eight out of ten people are satisfied with the availability and quality of care. Health spending is just under ten percent of GDP, and life expectancy exceeds the OECD average by several years. Still, the financial safety net is weaker than many believe. Only about 62 percent of spending is funded through mandatory prepayment, compared to 76 percent across the OECD. Out-of-pocket expenses account for roughly 29 to 30 percent of total health spending, significantly higher than the rich-country average of about 18 percent. For most minor illnesses, the system seems generous. However, for primary conditions, especially involving uncovered services or medications, costs can quickly accumulate.

Cancer policy illustrates this issue. Since the mid-2000s, copayment rates for insured cancer services fell to 10 percent and then to 5 percent. Despite aid programs, low-income households with cancer still face a high risk of catastrophic health spending. Nearly 40 percent of families with a cancer patient spent over 10 percent of their income on medical care annually, even after insurance payouts. When the household head loses their job, the risk of extreme financial hardship increases, with about 26 percent of Korean workers diagnosed with cancer losing their jobs within a year. This highlights Korea's health income loss: bills and wages moving in opposite directions, threatening household stability.

Why medical coverage without income security is not enough

Korea’s labor market and pension system turn health shocks into lasting problems. The country has long working hours and early exits from stable jobs. Many workers leave large firms in their fifties under “peak wage” systems that compress pay and encourage early retirement. They often transition into temporary, part-time, or informal jobs with lower wages and fewer benefits. By 2023, people aged 65 and over accounted for just over 20 percent of the population, yet almost 40 percent lived in relative poverty. Over half of seniors between 65 and 79 expressed a desire to keep working, primarily citing basic living expenses as their reason. When a serious illness strikes a household already dependent on unstable work, national health insurance may keep hospital doors open, but it cannot maintain wages.

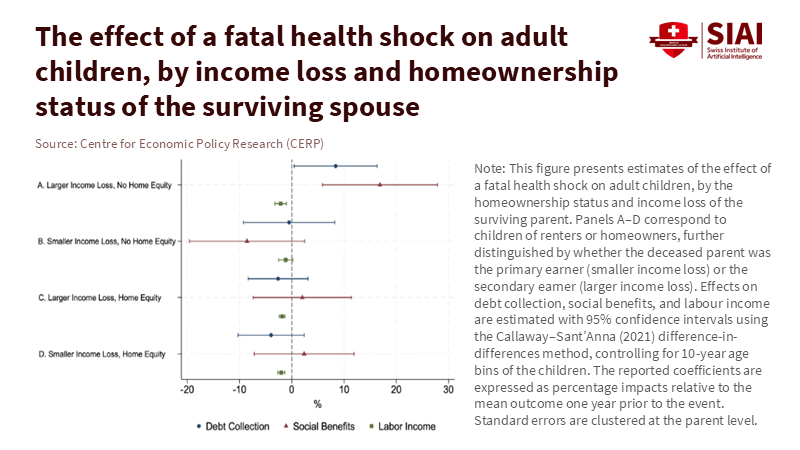

Other wealthy countries manage this risk quite differently. In Sweden, for example, universal health insurance is paired with strong income support for workers who become ill or die. Employers cover the initial sick leave period, paying around 80 percent of wages, and then a national agency takes over with earnings-related benefits. If a worker dies, survivor pensions and other benefits can replace over half of the lost income for a surviving spouse, especially at lower income levels. Recent research using detailed data from Sweden shows that when a spouse passes away, the default rate on debts rises by about 25 percent, especially impacting renters and their adult children. This occurs in a system that provides far stronger income protection than Korea’s. In Korea, where many families have limited assets and small pensions, health-related income losses after a health crisis often lead to debt, forced relocations, and long-term instability.

What the Korean health income loss means for students and schools

For schools and universities, these trends are very real. They show up in attendance records, withdrawals, and the worried faces of students who must juggle two part-time jobs while attending classes. When the primary earner in a family falls ill, teenagers may refuse private tutoring, postpone preparation for entrance exams, or drop out of vocational programs. University students might transition from full-time study to irregular jobs or take leaves to provide care at home. Tuition support typically depends on grades or general need, rather than unexpected health shocks. Thus, Korea's health income loss affects education in indirect yet significant ways. It limits choices well before graduation and steers students from vulnerable households into narrower, riskier paths.

Educators and administrators can't resolve the income side of welfare on their own, but they can take action. Schools can create early warning systems to flag sudden changes in attendance, performance, or fee payments and treat these as possible indicators of family health crises. Universities can provide emergency funds and flexible learning options for students whose parents or spouses face serious illness. Counseling centers can learn to inquire not only about stress and depression but also about financial pressures related to health shocks. Curricula in civics, economics, and health education can incorporate real stories of Korea's health income loss, showing students how social insurance, disability benefits, and additional coverage function. Each of these steps positions income security as part of student welfare, rather than a personal issue left to chance.

At the same time, education policy can serve as a long-term safeguard against health-related income loss. When older workers or surviving spouses lose their primary source of income due to illness or death, they frequently attempt to return to the labor market in low-paid, unstable jobs. Yet statistics reveal that while Korea’s senior poverty is alarming, many older Koreans want to keep working but lack the skills and credentials for new job opportunities. Programs aimed at midlife and later-life education for caregivers and widows emerging from health crises could turn that desire into real opportunities. A health crisis that reduces wages today could lead to subsidized training tomorrow, rather than a descent into long-term insecurity. Connecting income-based education loans, grants, and career services to documented health events would make Korea's health income loss a starting point for support rather than a sign that a family has fallen through the cracks.

From hospital bills to household balance sheets

What would it look like to redesign Korea’s health protection around households instead of hospitals? The first step is recognizing that medical coverage and income security are interconnected. National insurance can cover most direct costs of severe illnesses for many households, especially when targeted aid programs supplement benefits. Still, a health shock that eliminates half a family's earnings will feel catastrophic, even if medical bills are low. Policymakers should therefore enhance wage-loss protection tied to illness, with contributions collected through tax and social insurance systems rather than relying solely on voluntary employer benefits. Coverage must also extend to self-employed and irregular workers who comprise an increasing portion of the labor market. Without this, Korea's health income loss will persist as a private crisis embedded within a public system.

A second step is to safeguard families’ basic assets when they face severe or terminal health shocks. Evidence from Sweden indicates that defaults following a spouse’s death arise more from a lack of wealth to absorb the loss than from immediate income loss. In Korea, where home ownership and pension wealth vary widely, a similar trend likely exists. Policymakers can respond with temporary measures to prevent aggressive debt collection for households experiencing advanced cancer or recent bereavement, along with direct support for rent or mortgage payments for low-income families. Survivor pensions, minimum income guarantees, and targeted housing assistance are tools that can be tailored to Korea's specific risk of health-income loss, rather than to age or employment history alone. The aim is straightforward: no family should have to choose between completing treatment and keeping a child in school.

The final step involves both cultural change and institutional reform. The troubling idea that it is “cheaper to die” after a cancer diagnosis reflects a perception of illness as a personal financial issue. It teaches kids that the cost of care is linked to their parents’ wages and their own future opportunities. Korea’s success in building a fast, technically strong health system shows the country can move just as quickly on the financial side if it chooses. A system that tracks survival rates while overlooking household finances only fulfills part of its role. Suppose we wish health policy to support mobility and dignity across generations. In that case, we must consider a patient’s income as another essential sign to monitor. The real test of future reform will be whether Korea's health income losses become less frequent, shorter, and less severe than they are today.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Anadolu Agency. (2025). South Korea logs highest retired population poverty rate among OECD countries. Based on Statistics Korea data on relative poverty among seniors.

AsiaNews. (2025). South Korea has the worst poverty rate for seniors among OECD countries. Based on data from Statistics Korea and the OECD.

Choi, J.-W., Cho, K.-H., Choi, Y., Han, K.-T., Kwon, J.-A., & Park, E.-C. (2014). Changes in economic status of households associated with catastrophic health expenditures for cancer in South Korea. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention, 15(6), 2713–2719.

Human Rights Watch. (2025). Punished for getting older: South Korea’s age-based policies and older workers. Human Rights Watch report on mandatory retirement, peak wage systems, and precarious work among seniors.

Jung, H., & Lee, J. (2021). Estimating the effectiveness of national health insurance in covering catastrophic health expenditure: Evidence from South Korea. PLOS ONE, 16(8), e0255677.

Kim, S., Kwon, S., & others. (2015). Impact of the policy of expanding benefit coverage for cancer patients on catastrophic health expenditure across different income groups in South Korea. Social Science & Medicine, 138, 241–251.

Korea Times. (2024). Yearly working hours for Koreans fall by 200, but remain far longer than OECD average. The Korea Times, based on data from the Ministry of Employment and Labour and OECD.

Majlesi, K., Molin, E., & Roth, P. (2024). When loss strikes twice: Severe health shocks and financial well-being. Working paper using Swedish administrative data on mortality, income, and default.

Min, H. S., et al. (2018). Supporting low-income cancer patients: Recommendations for the public financial aid program in the Republic of Korea. Cancer Research and Treatment, 50(4), 1234–1245.

OECD. (2023). Health at a Glance 2023: Country note – Korea. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

World Bank. (2024). Out-of-pocket expenditure (% of current health expenditure) – Korea, Rep. World Development Indicators, 2023 data.

Yoo, K. J., et al. (2025). South Korea’s healthcare expenditure: A comprehensive review. The Lancet Regional Health – Western Pacific.

Comment