Borrowed Time: Education, Power and the Coming US Federal Debt Crisis

Input

Modified

US interest costs are soaring and debt is mounting This US federal debt crisis squeezes education and future investment The article urges early fiscal reform that shields human capital

In fiscal year 2025, the United States is set to spend about 970 billion dollars on net interest payments. This amount exceeds the country's defense spending. These interest payments will take up roughly 19 percent of all federal revenues and about 3.1 percent of GDP. We are currently spending more to pay for past decisions than to secure the country or invest in future generations. This situation illustrates the gradual unfolding of the US federal debt crisis. It isn’t about an immediate default, but rather a steady redirection of public funds away from education, research, and opportunity, toward payments to past creditors. The pressing question is not whether this path is sustainable, but whether policymakers will act now to safeguard public goods that foster growth or continue on this trajectory until that choice is made for us.

Then and Now: The Shape of a US Federal Debt Crisis

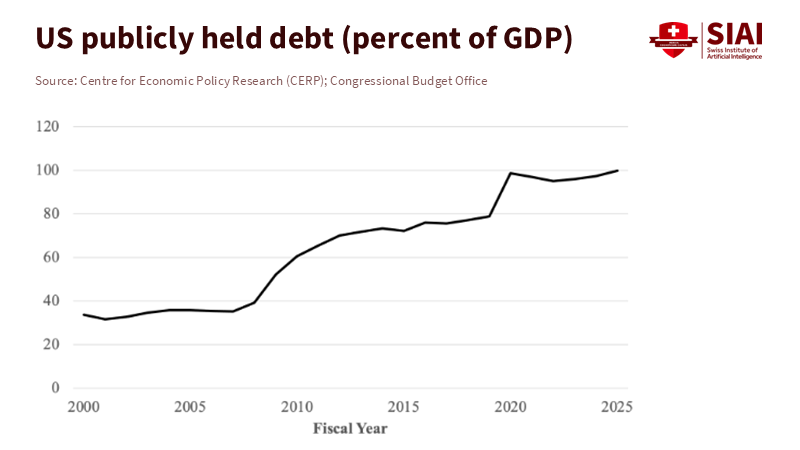

The numbers are precise. By mid-2025, total federal debt will reach about 119 percent of GDP, with public debt around 95 percent of GDP. According to the Congressional Budget Office, public debt is projected to rise to about 156 percent of GDP by 2055 due to aging, health care costs, and increasing interest costs. Recent analysis indicates that if new proposals are added, the debt ratio could reach around 183 percent of GDP by the mid-2050s. Research by the Penn Wharton Budget Model suggests that markets are unlikely to support public debt much above 200 percent of GDP. Even under favorable conditions, the US has approximately two decades to change direction before debt dynamics become unstable. This should concern all citizens, as it highlights the need for collective awareness and action to prevent economic instability.

To understand how we arrived at this point, we should revisit the lost hope of the 1990s “New Economy.” After World War II, the US took on the role of the West's financial and security leader. At first, it experienced surpluses, then increasing deficits as it provided security and dollar liquidity worldwide. In the 1990s, the narrative changed. A mix of strong productivity growth, defense cuts after the Cold War, and tax increases briefly produced primary budget surpluses. Unemployment decreased, inflation remained low, and Washington even discussed paying off the national debt.

However, this calm situation relied on global factors as much as domestic success. After the 1997-98 Asian financial crisis, many East Asian economies built up large foreign currency reserves, mainly in US dollars. These reserves, along with strong foreign demand for “safe” US securities, contributed to what economists later termed a global savings surplus. This lowered borrowing costs for the US and helped finance both private and public deficits. Viewed from 2025, the conclusion is sobering. The New Economy wasn’t a lasting model where the US could spend freely while maintaining declining debt ratios. It was a result of fortunate circumstances, including rapid productivity gains and a one-time surge in foreign demand for US safe assets. As these favorable conditions disappeared, the debt ratio began to rise again, and interest rates are no longer near zero.

Global Safe Assets and the US Federal Debt Crisis Mirage

This is where the optimists argue against the grim view. The US still produces the world’s primary reserve currency. In every recent crisis—from the global financial collapse to the pandemic and the latest geopolitical tensions—investors have flocked to the dollar. Commentators in the markets often describe the dollar as the world's "cleanest dirty shirt." It has flaws, but it’s better than other options. As long as this perception remains, they argue, claims of a US federal debt crisis are exaggerated. Yields will fluctuate with the business cycle, but Treasuries will always have buyers. The Spanish empire of the sixteenth century, which defaulted multiple times when lenders finally lost trust, is seen as ancient history—no longer a relevant comparison for a superpower in the twenty-first century.

However, the history of global capital flows suggests a more cautious perspective. After the Asian crisis, emerging economies in East Asia and elsewhere accumulated large foreign currency reserves, primarily in dollars. By the mid-2000s, foreign investors accounted for over half of the net issuance of highly rated US securities in some years, including Treasuries and agency bonds. Countries that had experienced sudden stops of capital flow in the 1990s chose to insulate themselves by financing US deficits. This trend continues today, joined by European and Gulf investors seeking safe, deep markets. This consistent foreign demand has kept US interest rates lower than they might otherwise be. Still, it has also created a weakness: if trust in US fiscal management fades, even small shifts in foreign investment could quickly push borrowing costs higher.

The comparison with Spain isn’t about specific numbers; it’s about how quickly attitudes can change. In the late 1500s, Philip II’s crown managed increasing debt for decades while defaulting multiple times. Historical analyses show that debt service claims often accounted for a large share of royal revenues before creditors finally refused to lend further. Today’s US ratios are measured against GDP, not real income, and the institutional context is very different. However, the basic lesson is relevant. An issuer that assumes its safe-asset status is endless might suddenly find that the market’s patience has run out. For policymakers and citizens alike, understanding this history underscores the importance of maintaining fiscal discipline to preserve economic stability for future generations.

Education in the Shadow of a US Federal Debt Crisis

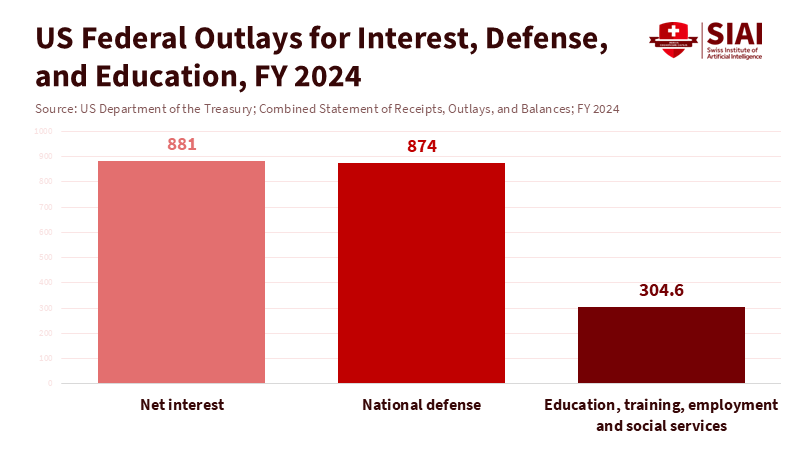

For education systems, the main issue is not whether the US will face an obvious “bankruptcy” moment. It is how rising interest costs gradually eliminate investments in human capital long before any formal crisis arises. Consider the budget figures that are already apparent today. Between 2023 and 2024, net interest payments increased from about 658 billion dollars to around 880 billion, and are projected to reach roughly 970 billion in 2025. As a share of federal revenues, interest is expected to hit about 18-19 percent by the end of 2025 and to exceed 22 percent by the mid-2030s. Under higher-rate scenarios, independent forecasts indicate that interest could consume nearly one-third of federal revenues by the mid-2030s. Every extra dollar spent on interest is a dollar that can’t support Pell Grants, research universities, teacher salaries, or community colleges.

Federal forecasts now predict net interest payments will surpass all non-defense discretionary spending within the next thirty years. This category includes most federal support for education, ranging from early childhood programs to student aid and research grants. Meanwhile, the share of GDP used for debt service is projected to rise from just over 3 percent now to more than 5 percent by the 2030s, exceeding previous peaks. When interest costs start to compete with spending on Social Security, Medicare, or defense, the political urge to cut “unnecessary” spending elsewhere grows. In past budget-tightening periods, education budgets have often been easier to cut than pension benefits or health entitlements because their beneficiaries are widespread and benefits accrue over years.

The outcome is a risk of gradual austerity for schools and universities, even while overall GDP continues to grow. States already face increasing retirement and healthcare costs that limit funding for higher education, pushing more of the burden on students and families. Suppose federal financial capacity declines at the same time, matching grants, research funding, and emergency support become tougher to maintain. The threat is not only fewer resources but also more uncertainty: cuts during downturns followed by rushed, poorly designed increases when political pressure rises. For students, this means less consistent support, higher tuition, and underfunded institutions—the opposite of the steady investment needed for long-term growth.

Choosing a Different Path through the US Federal Debt Crisis

If the New Economy of the 1990s was built on a fortunate surge of foreign savings and a peace dividend, the next phase must focus on intentional choices. Neither Japanese investments in the 1980s nor, now, Chinese savings can be counted on to support a new era of easy deficits. A practical strategy starts with recognizing that there is no easy solution to stabilize the debt ratio once it approaches 100 percent of GDP. A combination of higher revenues and slower spending growth is necessary. The policy question is whether that combination is pre-planned with clear rules that protect education and other growth-enhancing investments or left to market forces under pressure.

For the US, a reasonable goal could involve maintaining public debt at today's level relative to GDP, allowing it to rise during deep recessions but requiring it to decrease during expansions. This could be supported by a medium-term “fiscal corridor” with automatic triggers. If deficits exceed a specific range, phased-in tax increases and spending limits would take effect unless Congress specifically overrides them with a supermajority. Another “golden rule” could ensure that any new borrowing outside of recessions is linked to investment rather than current expenses—funding infrastructure, research, and education instead of permanent tax cuts or open-ended benefits. Within such a framework, policymakers would still face difficult decisions, but they would do so recognizing education as a vital asset rather than a secondary concern.

Educators, administrators, and students should not be passive in this discussion. They can demand that any serious plan to reduce debt treats human capital as essential. This may involve tying future revenue measures—like expanding the tax base or closing loopholes—to increased need-based student aid and research funding. It may require stronger automatic stabilizers for education budgets so that funding increases during downturns rather than decreases. It certainly necessitates incorporating basic financial literacy into curricula, helping the next generation understand how today’s budget choices affect their future opportunities and responsibilities. The alternative is a focus on short-term fixes, in which education becomes an easy target for cuts.

The choice remains, but the timeframe is shrinking. Interest costs have already outpaced some key areas of the federal budget, including national defense and, at times, Medicare. Without a change in direction, they will soon overshadow everything else. If we recognize that a US federal debt crisis is a current, measurable shift in how the budget is allocated, the importance of education becomes clear. A country that spends more on past commitments than on its students is not merely courting financial danger; it undermines the very foundation of its future growth. The moment to create a new fiscal plan—one that stabilizes debt while prioritizing investment in education—is now, before rising interest costs shut down better options.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

American Action Forum (2025). “Sizing Up Interest Payments on the National Debt,” 28 October.

Auerbach, A. and Gale, W. (2025). “Then and now: A look back and ahead at the US federal budget.” VoxEU, 24 November.

Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget (2025). “Interest Costs Could Explode from High Rates and More Debt,” 20 May.

Congressional Budget Office (2025). “Long-Term Budget Outlook: 2025 to 2055.”

Council on Foreign Relations (2023). “The U.S. National Debt Dilemma.”

Drelichman, M. and Voth, H.-J. (2014). “The Sustainable Debts of Philip II: A Reconstruction of Castile’s Fiscal Position, 1566–1596.” Journal of Economic History.

Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco (2003). “Foreign Exchange Reserves in East Asia: Why the High Demand?” Economic Letter.

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (2025). “Federal Debt: Total Public Debt as Percent of Gross Domestic Product (GFDEGDQ188S).”

House Budget Committee (2024). “Interest Costs Surpass National Defense and Medicare Spending,” 16 May.

Penn Wharton Budget Model (2023). “When Does Federal Debt Reach Unsustainable Levels?”

Peter G. Peterson Foundation (2025). “Interest Costs on the National Debt: Monthly Interest Tracker.”

US Department of the Treasury (2025). “Financial Report of the United States Government: An Unsustainable Fiscal Path.”

Comment