Eurozone Debt Contagion and French Risk

Input

Modified

French fiscal stress is raising the risk of eurozone debt contagion Shocks in France or Italy would spill into Spain, Greece, and the Balkans through banks and bond markets A permanent ECB–ESM backstop is needed to protect public investment, especially education

In a primary euro government bond index, almost one in four euros is now lent to the French state. French bonds make up about 24% of that benchmark, surpassing Italian bonds and even German Bunds. Meanwhile, France's public debt has risen to roughly 113-114% of GDP and is projected to approach 120% by the end of the decade. Deficits remain close to 6% of GDP, and interest costs are expected to be the largest item in the budget. Ratings agencies have begun to respond by downgrading the country's credit rating and warning about fiscal drift and political deadlock. Average debt in the euro area is around 88% of GDP, and global bond markets are preparing for record sovereign issuance in 2025. In this context, eurozone debt contagion is a genuine concern. When a borrower as significant as France struggles, every treasury from Berlin to Athens takes notice.

Eurozone Debt Contagion in a New Fiscal and Security Environment

The euro area enters the mid-2020s with significantly more debt, rising interest rates, and a more challenging security situation than a decade ago. Public debt in the currency union is slightly above 88% of GDP, an increase from pre-pandemic levels. France is over 113% of GDP, Italy is close to 138%, and Greece exceeds 160%. Germany appears safer at about 62%, but its trend is slowly moving upward. Monetary conditions have changed, making it costly to roll over old bonds. Advanced economies are likely to issue around 17 trillion dollars of new sovereign debt in 2025, up from about 14 trillion in 2023. This crowded market leaves less room for mistakes among large euro members. A rise in perceived risk must result in clearly higher yields.

A security policy introduces a significant new factor, elevating eurozone debt contagion to the agenda. The old NATO guideline of spending 2% of GDP on defense has become a baseline rather than an aspiration. All allies are expected to meet this target, and some voices now suggest a target of 3% or more. European NATO members already spend nearly half a trillion dollars annually on defense, and those numbers are likely to climb. At the same time, US commitments to European security seem less confident than before. If Washington further reduces its involvement, Europe will need to finance more of its defense over the long term. This additional burden compounds already high debt ratios in France, Italy, and increasingly, Germany. Strengthening regional fiscal coordination, establishing common debt management frameworks, and enhancing crisis response mechanisms are essential to mitigate contagion risks and promote financial stability across the eurozone.

How Eurozone Debt Contagion Spreads Through Bond Markets

The last euro crisis demonstrated how quickly local stress can escalate into a systemic shock. What began with a sudden halt in cross-border capital flows into a few member states became a broader sovereign debt crisis when governments had to step in for retreating private investors. The process is straightforward. Investors reassess risk in a country they perceive as weak. Domestic banks in that country are already heavily exposed to their own government's bonds, which regulators view as safe and liquid. Yields spike, bond prices drop, and weakened bank balance sheets lead to reduced lending at home and across the region. Global funds then search for 'the next Italy' or 'the next Greece,' selling those bonds preemptively. This chain reaction occurs through interconnected banking systems, shared investor sentiment, and the common currency, illustrating how localized debt issues can trigger widespread financial instability.

Current euro bond market structures make this dynamic harder to manage. French bonds account for about 24% of a key eurozone treasury index, Italian bonds around 22%, and German Bunds roughly 19%. Funds that follow or closely track that benchmark cannot discard French debt without reassessing their exposure to the entire region. Banks in "core" economies hold significant portfolios of French and Italian bonds as liquid buffers. In many "peripheral" nations, particularly in Southern Europe and the Western Balkans, banking systems remain tied to firms based in Italy and, to a lesser extent, Greece and France. Before the last crisis, foreign banks made up most of the banking assets in several Balkan states, with Greek banks controlling a substantial share. When these parent banks encountered stress, they reduced lending across their networks. A similar pattern may emerge again if eurozone debt contagion is sparked by a sharp reassessment of French or Italian risk, impacting Spain, Portugal, Greece, and their neighbors, even if those countries are not at the center of the crisis.

Why France and Italy Are New Test Cases for Eurozone Debt Contagion

France has become a clear example of how a core country can become the focal point of eurozone debt contagion. Its public debt has surpassed 113% of GDP and is expected to continue rising, heading toward 120% later this decade. The budget deficit remains high, close to 6% of GDP, and debt has reached about €3.3 trillion. Interest payments are projected to increase from around €55 billion in 2025 to over €70 billion by 2027 as older, cheaper bonds mature. Ratings downgrades have occurred, citing political fragmentation and slow fiscal adjustments. Markets have been teetering on a shift in their perception of French risk. At one point, French ten-year yields briefly surpassed Greek yields for the first time in many years, and the spread over German Bunds reached its highest level in over a decade. When a state that represents a quarter of a key euro bond index starts to behave more like a peripheral borrower than a safe core issuer, it sends a strong warning about the system.

Italy represents a classic case of gradual vulnerability within the euro. Its debt ratio is just under 138% of GDP and is expected to rise unless growth surprises positively or fiscal consolidation accelerates. Interest spending is projected to rise to about 4% of GDP by the late 2020s, and the Treasury must refinance significant amounts of maturing debt at rates well above those in recent years. For the moment, market sentiment is relatively calm. Italian ten-year bonds have a spread of less than one percentage point over Bunds, near the low end of the range seen over the last decade. This calm reflects several factors: inflows from European recovery funds, a rebound in tourism, relatively healthy bank balance sheets, and a strong belief that the European Central Bank will intervene if spreads widen disorderly. However, this calm is precarious. Suppose investors start doubting the strength of EU fiscal rules. In that case, Italy's stability, the ECB's willingness to act, and its size and starting debt levels make it a natural amplifier of eurozone debt contagion to Spain, Portugal, Greece, and beyond.

Germany is present in this discussion, but is not shielded from risks. Its debt ratio, around 62% of GDP in recent data, still positions it as a relatively haven. However, Germany also faces a prolonged investment challenge in defense, infrastructure, and the green transition. Projections indicate that these priorities could elevate German debt to 70-80% of GDP by the end of the decade, depending on growth and the interpretation of current fiscal rules. Ten-year Bund yields have already climbed to the mid-2% range, and the country's own interest costs are set to rise. In the short term, panic in Paris or Rome might still draw investors to German bonds, lowering yields. Over time, though, the cost of repeated rescue efforts for other members would lead to higher German borrowing needs and an increased risk premium on Bunds. This illustrates how eurozone debt contagion can return from the periphery to the core, challenging the belief that Germany can remain separate from the rest of the currency union.

From Crisis Management to a Permanent ECB-ESM Backstop

What does all this mean for policymakers and the education community, as they train future leaders and analysts? The first lesson is that risk cannot be confined within national borders in a monetary union. Trade patterns, banking networks, and shared bond indices connect France, Italy, Spain, Greece, and the Western Balkans into a single financial system. The last crisis showed that a sudden halt to cross-border flows can trigger a wave of sovereign stress. The difference today is that the foundation is more fragile. Debt ratios are higher. Interest rates are increased. Obligations for defense spending are heavier and less confident. In this context, improvising tools during a crisis is too risky. A reliable response to eurozone debt contagion must be permanent, predictable, and clearly understood by markets and citizens.

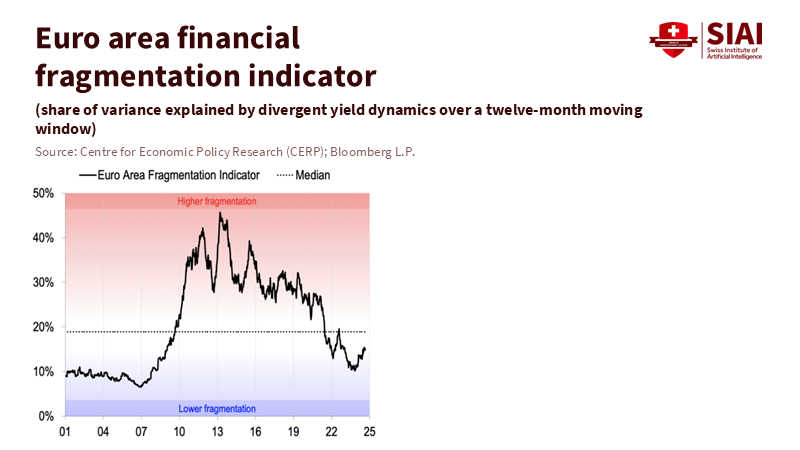

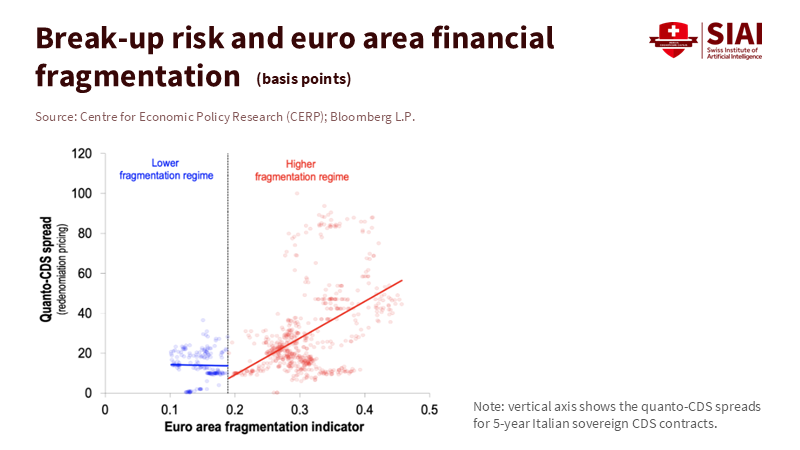

This calls for a stronger central backing anchored in the European Central Bank and the European Stability Mechanism. Over the past decade, the ECB has developed tools to contain unwarranted spreads, from earlier bond-buying programs to new instruments specifically designed to counter fragmentation. However, these tools are still subject to political sensitivities. A more robust system would define in advance the conditions under which the ECB and ESM intervene together. For instance, if a member state's spreads exceed levels consistent with its fundamentals—such as debt levels, trend growth, and the primary balance—the backstop would automatically trigger within a specified range. Support would come with clear and limited conditions focused on medium-term debt sustainability and reliable statistics, rather than meticulous control over every budget line. This framework would address the classic moral-hazard critique while still preventing self-fulfilling panic, which drives eurozone debt contagion.

For educators and administrators, the implications are concrete, not abstract. Higher sovereign borrowing costs directly affect the price of long-term public investments, such as schools, universities, and research infrastructure. For example, France's increasing interest bill could squeeze funding for universities and vocational training at a time when Europe needs more skills and innovation to foster growth. University leaders and school systems, particularly in Spain, Greece, and the Balkans, must prepare for more unpredictable funding if large states falter and eurozone debt contagion is mishandled. This requires adopting scenario-based budgeting, setting aside modest reserves during prosperous times, and utilizing European-level programs and development banks wisely. It also necessitates updating curricula in economics, public policy, and international relations. Students should view sovereign risk, security policy, and education budgets as interconnected parts of a single system, rather than separate subjects. Only then will the next generation of leaders be equipped to establish rules that safeguard both financial stability and the knowledge base critical to Europe's future.

The statistic that began this article is significant. When nearly a quarter of a core euro bond index depends on one heavily indebted country, vulnerability is built into the system. Without a transparent and credible central support system, concerns about French or Italian debt will not stay confined to Paris or Rome. They will ripple through index funds, bank portfolios, and NATO-influenced defense budgets, raising debt-service costs for Berlin, Athens, and Belgrade while forcing difficult decisions about which programs to cut. Education, training, and research will likely be among the first targets, even though they are crucial tools for Europe's prosperity and security. Eurozone debt contagion is not just a financial risk; it poses a threat to Europe's human capital. Policymakers now face a stark choice: create a planned, rule-based rescue system that protects long-term investment, or stumble from one hastily arranged bailout to the next, allowing each shock to weaken the foundations of Europe's educational institutions.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Baldwin, R., & Gros, D. (2015). What caused the Eurozone crisis? Centre for European Policy Studies Commentary.

European Central Bank. (2024). Escaping stagnation: Towards a stronger euro area. Speech, 2 October 2024.

European Central Bank. (2025a). Financial Stability Review, May 2025.

European Central Bank. (2025b). The euro area bond market. Speech, 11 June 2025.

European Commission. (2025a). Economic forecast – France.

European Commission. (2025b). Economic forecast – Germany.

Eurostat. (2025). Government debt at 88.2% of GDP in euro area.

Gros, D. (2015). The Eurozone crisis as a sudden stop: It is the foreign debt which matters. VoxEU.

International Monetary Fund. (2025). Euro Area Financial Fragmentation and Bond Market Stability. Working Paper.

Le Monde. (2024). French debt reaches a new peak of €3.3 trillion. 20 December 2024.

Le Monde. (2025a). Did Macron really add €1 trillion to France's national debt? 7 September 2025.

Le Monde. (2025b). S&P's downgrade of France's credit rating highlights growing political instability. 18 October 2025.

Morningstar. (2025). The Euro Government Bond Funds Least Exposed to French Debt.

NATO. (2025). Funding NATO.

OECD. (2025). Global Debt Report 2025.

Reuters. (2024–2025a). German debt projections and Stability Council assessments.

Reuters. (2025b). Italy's budget, debt targets and interest bill.

Tradeweb. (2025). Government Bond Update – September 2025.

YCharts. (2025a). France–Germany 10-year bond spread.

YCharts. (2025b). Italy–Germany 10-year bond spread.

Comment