Generative AI for Older Adults: Lessons from the Internet Age

Published

Modified

Older adults are missing out on generative AI Used well, it can boost independence and wellbeing Policy must make these tools senior-friendly

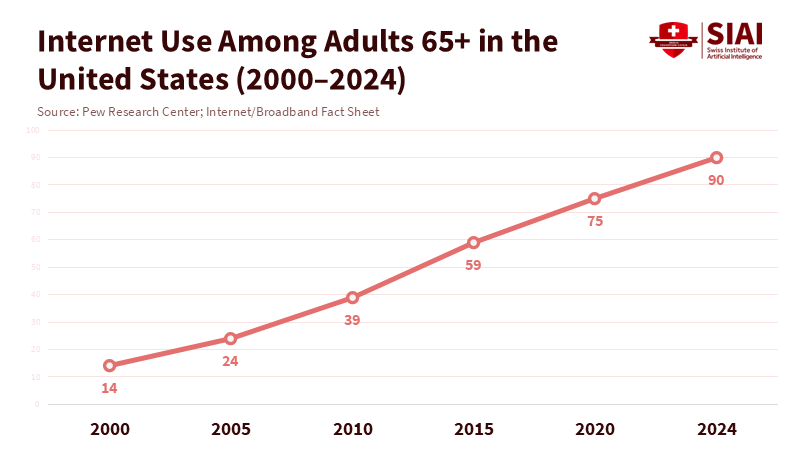

In 2000, only 14% of Americans aged 65 and older were online. By 2024, that number had risen to 90%. This shift is so significant that it's easy to forget how unfamiliar the internet once seemed to older adults. Today, many people in this age group video call their grandchildren, manage their bank accounts on smartphones, and consider YouTube their main TV channel. However, when we transition from browsing the web to using large language models, we see a regression. By mid-2025, only 10% of Americans aged 65 and older had ever used ChatGPT, compared with 58% of adults under 30. Data from Italy shows a similar trend: while three-quarters of adults are aware of generative AI, regular use remains concentrated among younger, more educated people. Generative AI for older adults is now in a position similar to the internet at the turn of the century: visible and popular, but mostly overlooked by seniors.

Most discussions of this gap view it as a job-market issue. Evidence from Italian household surveys indicates that using generative AI is linked to a 1.8% to 2.2% increase in earnings, about half a year's worth of additional schooling, and one-tenth of the wage benefit seen with basic computer use in the 1990s. From this perspective, younger, tech-savvy workers benefit first while older workers fall behind. While this interpretation isn’t wrong, it is limited. For those in their 60s and 70s, generative AI is less about income and more about independence, health, and social connections. The better comparison isn't early spreadsheets or email, but how the internet and smartphones changed well-being in later life once they became accessible and valuable. If we overlook this comparison, we risk repeating a 20-year delay that older adults cannot afford.

Generative AI for Older Adults and the New Adoption Gap

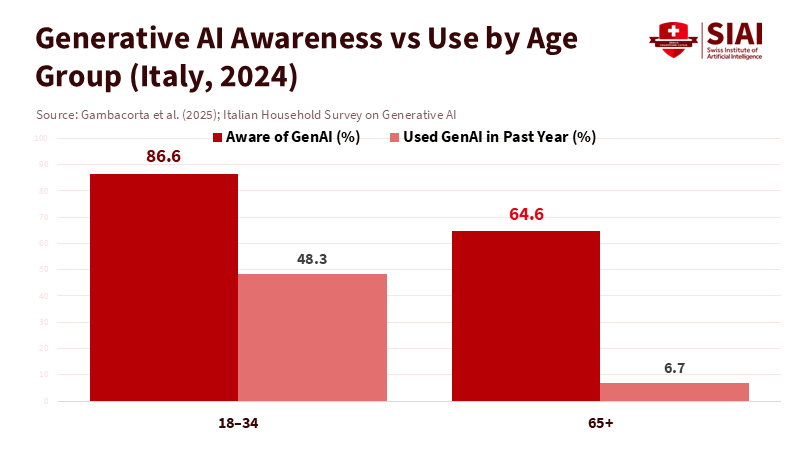

Recent Italian survey data highlight how significantly age influences the use of these tools. In April 2024, 75.6% of Italians aged 18 to 75 reported awareness of generative AI tools like ChatGPT, yet only 36.7% had used them at least once in the past year, and just 20.1% were monthly users. Age and education create a clear divide: adults aged 18 to 34 were 11 percentage points more likely to know about generative AI than those 65 and older, and among those aware of it, they were 30 percentage points more likely to use it. These are significant differences that reflect well-documented patterns in the "digital divide," where older adults see fewer benefits from new technologies and face steeper learning curves and greater perceived risks. Consequently, generative AI for older adults exists, but it is mostly outside their everyday activities.

Evidence from other countries shows that Italy is not an anomaly. A module in the U.S. Federal Reserve’s Survey of Consumer Expectations finds that awareness of generative AI now exceeds 80% among adults. Usage rates are slightly higher than those in Italy, but the same pronounced divides by age, education, and gender persist. Pew Research Center estimates that by June 2025, 34% of U.S. adults had used ChatGPT. The difference by age is stark: 58% of adults under 30 compared to 25% of those aged 50 to 64 and just 10% of those 65 and older. Across the EU, the Commission’s Joint Research Centre reports that about 30% of workers now use some form of AI, with adoption highest among younger, better-educated groups. Generative AI for older adults is thus developing within a framework of established digital inequality: seniors have achieved near-universal internet access. Still, they are once again marginalized by a new general-purpose technology.

This situation would be less concerning if the gains from adoption were solely financial. Estimates from Italy suggest that generative AI use provides only a modest earnings boost, much smaller than the benefits received from basic computer skills during the early computer age. Yet older adults interact with health systems, social services, and financial providers that are quickly integrating AI. If generative AI for older adults remains uncommon, the risk extends beyond reduced income; it also includes diminished ability to navigate services influenced by algorithms. The Italian data highlight another vital aspect: social engagement strongly predicts the use of generative AI, even after considering education and income. This finding mirrors decades of research on the internet, where social connections and perceived usefulness determine whether late adopters continue to use these tools. Understanding generative AI through this perspective is crucial, as it shifts the focus from “teaching seniors to code with chatbots” to integrating these technologies into the social and service settings they trust, thereby illuminating the true potential of AI for older adults.

What the Internet Era Taught Us About Late-Life Technology Adoption

The history of the web and smartphones illustrates how quickly older adults can close a gap once technologies become simpler and more relevant. In the United States, only 14% of those 65 and older used the internet in 2000; by 2024, that number reached 90%, just nine percentage points lower than the youngest age group. Home broadband and smartphone ownership reflect a similar trend: as of 2021, 61% of people aged 65 and older owned a smartphone, and 64% had broadband at home, up from single-digit levels in the mid-2000s. Even YouTube—a platform initially considered for teenagers—has seen use grow among older adults, with the percentage of Americans aged 65 and older using it rising from 38% to 49% between 2019 and 2021. In other words, older adults did not grow up digital. Still, once devices became touch-based, constantly connected, and integrated into social life, they underwent large-scale adaptation.

This access brought about not just convenience but also improved well-being. A study of adults aged 50 and older found that using the internet for communication, information, practical tasks, and leisure positively affected life satisfaction and, in terms of task performance and leisure, negatively correlated with symptoms of depression. An analysis of older Japanese adults revealed that frequent internet users enjoyed better physical and cognitive health, stronger social connections, and healthier behaviors than those who didn't use the internet, even after controlling for initial differences. Studies in England and other aging societies also show a link between regular internet use among seniors and higher quality-of-life scores. Overall, this research suggests that when older adults successfully incorporate digital tools into their daily lives, they often experience greater autonomy, social ties, and psychological resilience.

However, the evidence cautions against being overly optimistic. A recent quantitative study of older adults in a European country, using European Social Survey data, found that daily internet use is negatively associated with self-reported happiness, even while it is positively related to social life indicators. A 2025 analysis from China described a "dark side," noting that internet use is associated with improved overall subjective well-being. Still, it also creates new vulnerabilities, with hope being a key psychological factor. The takeaway isn't that older adults should disconnect; rather, it is about the intensity and purpose of their digital interactions. Well-designed tools that foster communication, meaningful learning, and practical problem-solving tend to enhance late-life well-being. In contrast, aimless browsing and exposure to scams or misinformation do not have the same effect. Generative AI for older adults will follow this same trend unless it is thoughtfully created and regulated.

Designing Generative AI for Older Adults as a Well-Being Tool

Suppose we view generative AI for older adults as an extension of digital infrastructure. In that case, its most impactful uses will be straightforward and practical. Older adults already interact with AI-driven systems when seeking public benefits, scheduling medical appointments, or navigating banking apps. Conversational agents based on large language models could transform these interactions into two-way support: breaking down forms into simple language, drafting letters to landlords or insurers, or helping prepare questions for doctors. Research on health and wellness chatbots shows that older adults are willing to use them for medication reminders, lifestyle coaching, and appointment help if the interfaces are user-friendly and trust is established over time. Early qualitative studies indicate seniors appreciate chatbots that are patient, non-judgmental, and aware of local context—not those filled with jargon or pushy prompts.

Labor market evidence suggests that the most significant benefit of generative AI for older adults may not be financial. Data from Italian households reveal that the earning boost associated with generative AI use is real but modest. For retirees or those nearing retirement, this boost may not matter. What is crucial is whether these tools can help maintain independence—allowing someone to stay in their home longer, manage a chronic condition more effectively, or remain active in community groups. Findings from England’s longitudinal aging study and similar research suggest that using the internet for communication and information improves quality of life and reduces loneliness among older adults. A growing body of research indicates that AI companions and assistants can help combat isolation. However, the quality of this evidence varies. Suppose generative AI for older adults can focus on these high-value functions. In that case, its social benefits may significantly outweigh its direct economic contributions.

Design decisions will shape this future. Surveys show that around 60% of Americans aged 65 and older have serious concerns about the integration of AI into everyday products and services. Classes offered by organizations like Senior Planet in the United States highlight this: participants are eager to learn, but they worry about scams, misinformation, and hidden data collection. For generative AI for older adults, "accessible design" has at least three aspects. First, interfaces must accommodate slow typing, hearing, or vision impairments, and interruptions; voice input and clear visual feedback can help. Second, safety features—such as prompts about scams, easy-to-follow source links, and skepticism regarding financial or health claims—should be built into the systems rather than added later. Third, tailoring matters: advice on pensions, care systems, or tenant rights must be specific to national regulations, not generic templates. Each of these elements lessens cognitive load and increases the chances that older adults will see AI as helpful rather than threatening.

Policy for Inclusive Generative AI for Older Adults

The European Union’s "Digital Decade" strategy aims to ensure that 80% of adults have at least basic digital skills by 2030. This goal should now expand to include proficiency in using generative AI to enhance well-being rather than detract from it. The most effective delivery channels are those already trusted by seniors. Public libraries, community centers, trade unions, and universities for older adults can host short, practical workshops where participants practice asking chatbots to rewrite scam emails, summarize medical documents, or generate questions for consultations. In Italy and other aging societies, adult education programs can pair tech-savvy students with older learners to explore AI tools together, turning social engagement—already a key factor in adoption—into a foundational design principle. Importantly, this training should not be framed as a crash course in “future-proofing your CV,” but as a toolkit for engaging with public services, managing finances, and maintaining social connections.

Governments and regulators also play a role in shaping the market for generative AI for older adults. Health and welfare agencies can create “public option” chatbots that provide answers based on verified information and acknowledge uncertainty, rather than pushing older adults toward less transparent private tools. Consumer protection authorities can mandate that AI systems used in pension advice, insurance, or credit scoring provide accessible explanations and clear appeal paths. Given the established links between internet use and better subjective well-being in later life, the onus should be on providers to demonstrate that their tools do not systematically mislead or exploit older users. Labor market policy is also essential. As AI becomes integrated into workplace software, employers should offer targeted training for older workers, recognizing that even modest earnings gains from generative AI can help extend productive careers for those who want to continue working.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Aldasoro, I., Armantier, O., Doerr, S., Gambacorta, L., & Oliviero, T. (2024a). The gen AI gender gap. Economics Letters, 241, 111814.

Aldasoro, I., Armantier, O., Doerr, S., Gambacorta, L., & Oliviero, T. (2024b). Survey evidence of gen AI and households: Job prospects amid trust concerns. BIS Bulletin, 86.

Bick, A., Blandin, A., & Deming, D. (2024). The rapid adoption of generative AI. VoxEU.

European Commission. (2025). Impact of digitalisation: 30% of EU workers use AI. Joint Research Centre.

Gambacorta, L., Jappelli, T., & Oliviero, T. (2025). Generative AI: Uneven adoption, labour market returns, and policy implications. VoxEU.

Lifshitz, R., Nimrod, G., & Bachner, Y. G. (2018). Internet use and well-being in later life: A functional approach. Aging & Mental Health, 22(1), 85–91.

Nakagomi, A., Shiba, K., Kawachi, I., et al. (2022). Internet use and subsequent health and well-being in older adults: An outcome-wide analysis. Computers in Human Behavior, 130, 107156.

Pew Research Center. (2022). Share of those 65 and older who are tech users has grown in the past decade.

Pew Research Center. (2024). Internet/Broadband Fact Sheet.

Pew Research Center. (2025). 34% of U.S. adults have used ChatGPT, about double the share in 2023.

Suárez-Álvarez, A., & Vicente, M. R. (2023). Going “beyond the GDP” in the digital economy: Exploring the relationship between internet use and well-being in Spain. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 10(1), 582.

Suárez-Álvarez, A., & Vicente, M. R. (2025). Internet use and the Well-Being of the Elders: A quantitative study in an aged country. Social Indicators Research, 176(3), 1121–1135.

Washington Post. (2025, August 19). How America’s seniors are confronting the dizzying world of AI.

Yu, S., et al. (2024). Understanding older adults’ acceptance of chatbots in health contexts. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction.

Zhang, D., et al. (2025). The dark side of the association between internet use and subjective well-being among older adults. BMC Geriatrics.

Comment