Digital bank runs and loss-absorbing capacity: why mid-sized banks need bigger buffers

Published

Modified

Digital bank runs can drain banks in hours, outpacing current LAC rules. Raise LAC for mid-sized, high-digital banks using uninsured-deposit and network metrics AI-amplified rumors heighten correlation, so stress tests and resolution must run on 24-hour clocks

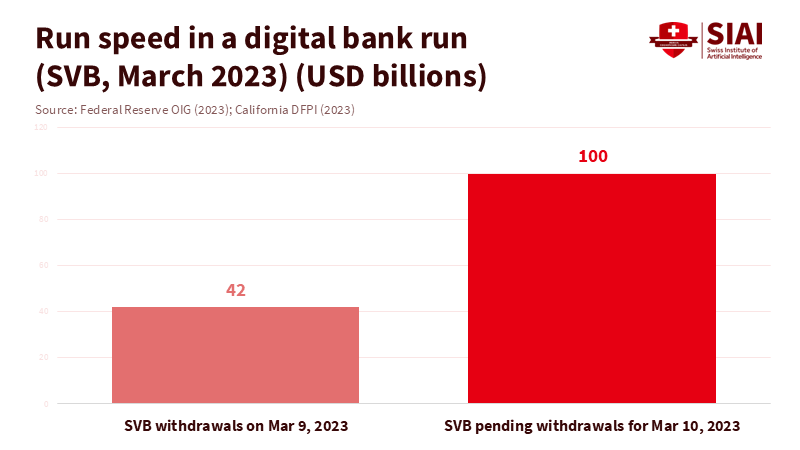

In March 2023, a single U.S. bank experienced a staggering $42 billion in customer withdrawals in just one trading day, representing a quarter of its total funding. The following morning, another $100 billion was poised to leave. Regulators had no time for a weekend rescue. The balance sheet, which would typically be dismantled over weeks, was emptied in a matter of hours. This alarming scenario is the new reality of digital bank runs. The rapid evolution of mobile banking, social media, and concentrated corporate depositors can transform mere rumors into full-blown funding crises almost instantly. However, our primary safety tool—loss-absorbing capacity (LAC) for resolution—still reflects a time of slower runs and primarily focuses on the largest global banks. If LAC is to shield the real economy from chaotic failures effectively, it must be recalibrated to match the speed and structure of digital panic. Buffers for mid-sized, digitally intensive banks must be increased and explicitly calibrated to the risk of digital bank runs, rather than being treated as an afterthought.

Digital bank runs and loss-absorbing capacity

Over the last decade, major regions have established resolution systems so that large banks can fail without disrupting the wider system or requiring taxpayer bailouts. The most prominent international institutions are subject to a common minimum standard for total loss-absorbing capacity (TLAC). This standard is designed to ensure that there is enough bail-in debt and capital to cover losses and restore a viable entity during resolution. For other systemic banks, the rules are more fragmented. A recent analysis by the Bank for International Settlements shows that while many countries now apply LAC-style rules to significant domestic banks, there is no uniform global baseline, and the standards vary widely. That variety might have been acceptable in a world of slow, queue-based runs. It seems much less reassuring after a funding shock that wiped out tens of billions within hours.

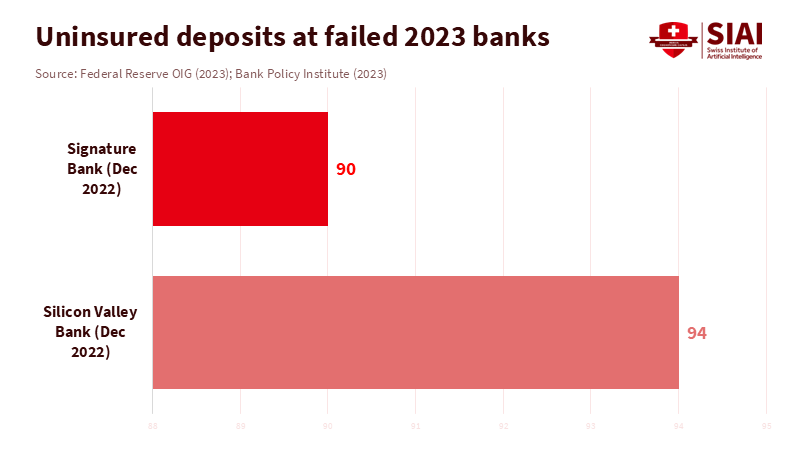

The turmoil of 2023 revealed how digital bank runs can turn mid-sized lenders into systemic threats on a new timeline. At Silicon Valley Bank, $42 billion in deposits were left on March 9, 2023, and requests for another $100 billion appeared overnight. First Republic then lost more than $100 billion in deposits in a single quarter as confidence vanished. Research using detailed social media data indicates that banks with high Twitter exposure lost more market value and experienced greater outflows of uninsured deposits during this period, even after accounting for balance-sheet risks. Observers have accurately labeled these events as digital bank runs, fueled by instant transfers and intense online scrutiny. However, LAC frameworks still tend to treat mid-sized banks as locally significant but manageable with modest buffers. The disconnect is apparent: resolution plans assume time and funding that digital bank runs no longer allow.

Measuring digital systemicity beyond size-based LAC

The main lesson from these cases is straightforward. Systemic importance is no longer determined solely by size, cross-border activity, or complexity. It is also about how quickly a bank can lose funding when narratives shift. Digital bank runs occur at the intersection of three features: large amounts of uninsured deposits, intense social media focus, and seamless digital channels. Research on the 2023 U.S. banking stress finds that banks with high Twitter exposure experienced equity losses about 6 to 7 percentage points higher than their peers.

Additionally, message volume predicted intraday losses and uninsured outflows. Central bank commentary supports similar conclusions: the Banque de France notes that digitalization and social networks worsened the Silicon Valley Bank run by making it easier to move uninsured deposits and spread panic. This means that the relevant funding profile now is not just "wholesale versus retail"; it also concerns how networked, uninsured, and mobile those funds are.

LAC policy must adapt to these changes. Instead of treating mid-sized banks as a uniform group that can maintain a thin layer of bail-inable instruments, supervisors should introduce a 'digital systemicity' factor when determining minimum LAC. This factor can utilize data already collected: the share of uninsured deposits, the proportion of funding from large corporate or venture networks, the use of instant payment channels, and fundamental indicators of a bank's public digital presence. While none of these metrics is perfect, together they can highlight where digital bank runs are most likely to happen quickly and in a coordinated manner. Where digital systemicity is high, LAC floors should be closer to those set for the largest banks, even if their total assets are lower. Recent work from global standard-setters already emphasizes the need to tailor LAC for non-global systemic banks; the next step is to integrate digital run risk into that calibration rather than treat it as an afterthought.

AI-driven contagion and the new calibration challenge

The risk landscape is shifting even more as artificial intelligence becomes central to information production and decision-making. A 2025 study in the UK on AI-generated misinformation finds that false but believable content about a bank's condition, spread through targeted social media ads, significantly increases the number of customers likely to move their money. The authors estimate that in some cases, £10 in ad spend could influence up to £1 million in deposits. The Financial Stability Board's 2024 evaluation of AI warns that generative models can amplify misinformation and help malicious actors trigger "acute crises," including bank runs, by lowering the cost of generating convincing narratives at scale. In simpler terms, creating the spark for digital bank runs is becoming cheaper, faster, and harder to monitor.

Simultaneously, the infrastructure that supports financial AI is highly concentrated. By mid-2025, the three largest cloud providers controlled about two-thirds of the global cloud infrastructure market. Many banks and market utilities now run their AI models on the same providers and tools. Supervisory studies on AI in finance highlight vendor concentration, herding, and limited visibility as significant sources of concern for financial stability. These trends matter for LAC because they increase the likelihood that many institutions will react to the same rumor in the same way at the same time. When AI systems promote and rank similar content across platforms, a piece of false news does not just reach one bank's clients; it hits overlapping communities of depositors within minutes. Thus, digital bank runs become more correlated among institutions, including mid-sized lenders that were never deemed 'systemically important' in the traditional sense. If LAC calibration overlooks this, it will be too low exactly where AI-driven contagion makes failure most disruptive. A more comprehensive approach to LAC calibration is needed to account for these new challenges.

Some argue that increasing LAC for a broader range of banks is too expensive and that better supervision or liquidity rules should manage digital stress. There is a cost: bail-inable debt is not free, and spreads may rise. However, post-crisis studies on stronger capital requirements suggest that the long-term impact on credit and growth is small compared to the benefits of reduced crisis risk. Moreover, LAC targeted at digital systemicity can be detailed. Banks with low uninsured deposits and limited digital reach would not see significant increases. Those with concentrated, mobile funding and a heavy reliance on public platforms would need larger buffers to account for the higher risks they entail. Liquidity support and supervision remain essential, but they cannot replace the need for readily available loss-absorbing resources when digital bank runs and AI-fueled narratives expose weaknesses in hours instead of days.

What must educators and regulators do now?

For regulators, the first step is theoretical. LAC should be viewed as a tool to manage digital coordination risk, not merely as a means of absorbing balance-sheet losses. This means integrating indicators of digital bank runs into both the scope and calibration of LAC. Authorities can begin by requiring banks with a certain level of digital systemicity to hold a higher minimum LAC, with a clear phase-in and rationale. Stress tests should consider run speeds similar to those seen in 2023, when a quarter of deposits can vanish in a day, and model shocks from AI-driven misinformation rather than just interest-rate or credit shocks. Resolution plans must also be quicker. Bail-in guidelines, communication plans, and temporary liquidity support mechanisms must be ready for execution around the clock, not just during a quiet weekend.

Educators and administrators also play an essential role. Programs in finance, law, data science, and public policy should now include digital bank runs as a regular topic, not just a niche study. Students preparing for roles in treasuries, central banks, or supervisory agencies need to analyze the 2023 events with real numbers: how deposit structures, social networks, and rumors combined to overwhelm existing buffers. Courses can integrate simple models that connect LAC levels to run speed and digital exposure, illustrating how additional bail-in debt impacts the options available to resolution authorities during stress. Cross-disciplinary modules that connect technology, psychology, and regulation—drawing on recent legal and economic analyses of bank runs in the digital age—will help future decision-makers understand why narrative dynamics are now at the center of discussions of stability.

The conclusion follows from the figure mentioned at the start. When $42 billion can exit a bank in one day and another $100 billion is lined up for the next, we are not facing a rare shock. We are observing the normal pace of panic in a world of digital bank runs and AI-driven information. LAC rules that disregard this reality are, by design, miscalibrated. Increasing buffers for mid-sized and digitally intensive banks is not about punishment; it is about acknowledging their new systemic impact and providing resolution tools with enough resources to function. If regulators adjust LAC with digital systemicity in mind, if banks accept that higher loss-absorbing capacity is the cost of operating in a hyper-connected market, and if educators prepare the next generation to think in these terms, the next digital run need not lead to a scramble for extraordinary support. The choice is clear: enhance LAC for our current world, or keep relying on safeguards built for a slower crisis that no longer exists.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Bank for International Settlements – Financial Stability Institute. (2025). Loss-absorbing capacity requirements for resolution: beyond G-SIBs (FSI Insights No. 69). Bank for International Settlements.

Bank for International Settlements – Financial Stability Institute. (2024). Regulating AI in the financial sector: recent developments and main challenges (FSI Insights No. 63). Bank for International Settlements.

Banque de France. (2024). Digitalisation – a potential factor in accelerating bank runs? Bloc-notes Éco, Post 382.

Beunza, D. (2023). Digital bank runs: social media played a role in recent financial failures, but could also help investors avoid panic. The Conversation.

Cookson, J. A., Fox, C., Gil-Bazo, J., Imbet, J. F., & Schiller, C. (2023). Social Media as a Bank Run Catalyst (working paper). Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation / Banque de France.

Financial Stability Board. (2024). The financial stability implications of artificial intelligence. Financial Stability Board.

Fortune. (2023, March 11). $42 billion in one day: SVB bank run biggest in more than a decade.

Ofir, M., & Elmakiess, T. (2025). Bank runs in the digital era: technology, psychology and regulation. Oxford Business Law Blog (blog summary of forthcoming law review article).

Reuters. (2023, April 24). First Republic Bank deposits tumble more than $100 billion in the first quarter.

Reuters. (2025, February 14). AI-generated content raises risks of more bank runs, UK study shows.

SIAI – McGowan, E. (2025). From model risk to market design: why AI financial stability needs systemic guardrails. Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence Memo Series.

U.S. Federal Reserve Board Office of Inspector General. (2023). Material loss review of Silicon Valley Bank, Santa Clara, California.

Comment