AI Chatbots in Education Won’t Replace Us Yet, But They Will Reshape How We Talk

Published

Modified

AI chatbots in education are mediators now, not replacements Set guardrails: upstream uses, training, human escalation, and source transparency Prepare for embodied systems next while protecting attention, care, and truth

In the United Kingdom this year, 92% of university students reported using AI tools, up from 66% in 2024. Only one in twelve said they did not use AI at all, and just one-third had received formal training. This shift in behavior in just twelve months is significant. It shows that adoption is moving faster than the pace of teaching methods. We face a hard truth in the coming months: whether we like it or not, AI chatbots in education are changing how learners ask questions, think, and respond. In the United States, the trend is slower but clear. A quarter of teens now say they use ChatGPT for schoolwork, double the share from 2023. We are not replacing human connection yet; we are channeling more of it through machines. If we want to protect learning, we must design for this reality, not deny it.

AI Chatbots in Education: The Near Future Is Mediation, Not Substitution

People often ask if bots will replace teachers or friends. This is the wrong question for the next five years. The right question is how much AI chatbots in education will mediate relationships among the people who matter most: students, teachers, and peers. The evidence shows both promise and risk. A 2025 meta-analysis finds that conversational agents can reduce symptoms of anxiety and depression in the short term. An extensive study published by consumer researchers reports that AI companions can reduce loneliness after use. However, the same research warns that heavy emotional use can lead to greater loneliness and less real-world socializing, especially for young people and some women. These aren’t contradictions; they are dose-response curves. Light, guided use can help. Heavy, unstructured use can harm. For schools, this suggests guidelines rather than outright bans. We should measure time and intensity, not just whether a bot is used.

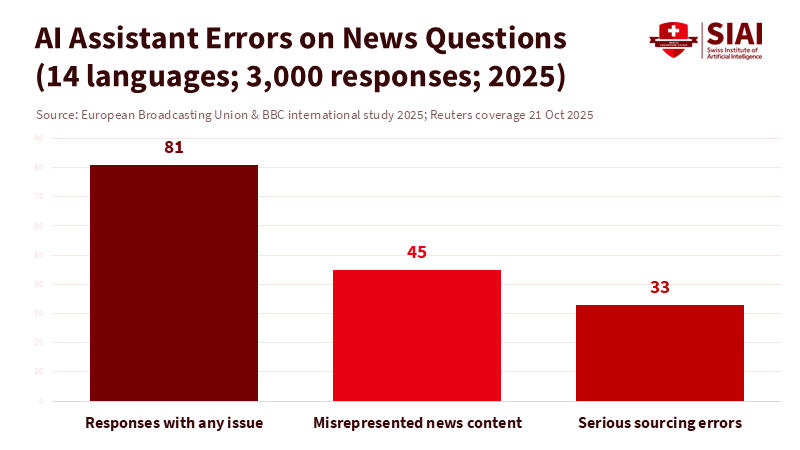

The second reason substitution is premature is accuracy. Current models still make confident errors. In news contexts, independent testing across leading assistants found serious problems in almost half of their responses, including broken or missing sources. In specialized areas, studies report ongoing hallucinations and inconsistent reasoning, even as performance improves on some tests. OpenAI itself has discussed the trade-off between aggressive guessing and error rates. Education demands high accuracy. A single wrong answer can derail understanding for weeks. That is why AI chatbots in education should scaffold thinking rather than replace human judgment. We should see them as powerful calculators that sometimes improvise, not as tutors that can work unsupervised.

A final reason is relational. Learning is social. Brookings summarizes extensive research: belonging and trust are crucial for attention, memory, and persistence. Students learn through connection, not just content. If we encourage them to replace people with bots too soon, we pay a cognitive cost. The goal isn’t to romanticize the classroom but to remember what the brain needs to develop. This biology should guide our policy choices for the next school year.

Designing Guardrails for AI Chatbots in Education

If mediation is in the near future, design is the immediate solution. First, we should establish use cases that are both common and safe. The UK survey that reported the 92% figure provides essential insights. Students lean on AI to explain ideas, summarize readings, and generate questions. These tasks can save time without replacing critical thinking, provided we require students to show their own synthesis. The same survey shows that fewer students paste AI-generated text into assignments. This area poses a risk where fluent output can earn grades. Policies should encourage students to engage more actively. Require planning notes. Ask them to compare sources—grade on the process as well as the final product. Make the human work visible again.

Second, we need to build human involvement into the tools. The authors from Brookings highlight findings that voice bots and gendered voices can increase emotional dependency for some users. This should prompt simple safeguards. When a student seeks emotional support, the bot should direct them to campus resources rather than act as a counselor. If prompts include self-harm or abuse, the system should stop and refer the matter to a human. This isn’t a ban on help; it’s a way to connect students with trained professionals. Public guidance from UNESCO and several national systems is already heading in this direction. Schools shouldn’t delay; they can contract for these features or demand them in procurement now.

Third, we should teach with the medium's strengths. Evidence suggests that small, supervised doses help, while heavy, unstructured use can be harmful. This should shape classroom practice. Limit the use of AI chatbots in education to specific minutes and tasks. Use them for brainstorming, to provide worked examples, or for checking unit conversions and definitions, and then move students into pair work or seminars. Keep the bot as a warm-up or a check, not as the primary focus. Teachers will need time and training to make this shift. Currently, only a minority of students report formal AI instruction at their institutions. This gap is significant and should be addressed with funding for training, release time, and shared lesson resources.

Finally, we must be honest about accuracy. Retrieval-augmented generation and chain-of-thought prompts can reduce errors, but they don’t eliminate them. In subjects where a wrong answer carries heavy consequences—such as chemistry labs, clinical note-taking, or legal citations—bots should be assistants, not authorities. Independent assessments show both promise and failure: high scores on some professional questions alongside significant errors in document tasks. Administrators should clearly define this distinction. They should also audit vendors on how they handle errors and display sources. If a system cannot show where an answer comes from, it isn’t ready for high-stakes use.

From Chatbots to Humanoids: What Changes When Bodies Enter the Classroom?

The concern that many people feel is not just about the text box. It’s about the physical presence. We are seeing early demonstrations of lifelike humanoids that move with fluid grace. Xpeng’s “IRON” sparked online rumors that a person was inside the shell. The company had to open the casing on stage to prove it was a machine. This is not an educational product but a warning. As embodied systems improve, the line between a friendly teaching assistant and a social partner will blur. The risks tied to chatbots—over-reliance, blurred boundaries, and distorted expectations—could grow when a device can track our gaze. Schools and educational ministries should address this early, before humanoid technology arrives at the school gate.

The social risks are real and not abstract. Media reports and early studies show that people develop deep attachments to AI companions. Some experiences are positive; people feel heard. Others are negative; users feel displaced or dependent. Some even report crises when a bot becomes an emotional anchor that it cannot safely manage. Regulators are starting to respond. Professional groups warn against "AI therapy." Some governments are discussing bans or limits on unsupervised AI counseling. Education should not wait for the health law. It needs its own rules for emotionally immersive systems used by minors and young adults. These rules should begin with clear disclosure, crisis management, and strict age limits. They should continue with a curriculum that teaches what machines can and cannot do.

There is also real potential if we maintain clear boundaries. Even simple embodied systems can capture attention and motivate practice. A robot that guides a lab safety routine with consistent movements can reduce errors. A bot that demonstrates physical therapy stretches accurately can help health students learn. However, the benefits depend on careful design. AI chatbots in education and their embodied counterparts should be clear about their limitations, explicit about their sources, and quick to defer to humans. If the device feels too human for its job, it probably is.

A Human-First Roadmap Before the Robots Get Good

What should leaders do now? Start by identifying the right horizon. Replacement is not imminent, but mediation is here. This requires rules and routines that keep people in charge of meaning, not just tools. First, create policies that distinguish between upstream and downstream uses. Upstream use—explanations, outlines, question generation—should be allowed with proper disclosure and reflection. Downstream use—finished writing, graded code—should be restricted unless explicitly required by the assignment. Second, link access to skill. Provide short, necessary training on prompt design, citation, error-checking, and bias. Guidance from UNESCO and OECD can inform these modules. Third, establish protocols for escalation and care. Configure systems so that emotional or medical concerns trigger a referral. This is good practice for adults and essential for minors. Fourth, demand transparency from vendors. Contracts should require source visibility, uncertainty flags, and logs that allow instructors to review issues when they occur.

Expect criticism. Some will claim this is paternalistic. However, the data support caution. Even favorable coverage of AI companions acknowledges the risks of distortion and dependence. The European Broadcasting Union's multi-assistant test highlighted high error rates on public-interest facts. OpenAI’s own analysis explains why accuracy and hallucination remain concerns. None of this leads to fear; it calls for thoughtful design. Educators are not gatekeepers against the future. They are the architects of safe pathways through it. By viewing AI chatbots in education as a communication tool rather than a replacement, we gain time to improve models and maintain the human elements that make learning effective.

We should also dismiss any panic about human interaction with machines. Many students are already engaging with them and often find short-term relief. The appropriate response is not to reprimand but to teach. Show students how to question a claim. Teach them to trace a source. Encourage them to compare a bot’s answer with a classmate's and a textbook's, and explain which they trust and why. Then, make grades reflect that reasoning. Over time, the novelty will wear off. What will remain is a new literacy: the ability to communicate with systems without being misled by them. That is progress, and it lays a foundation for the day when robots become more capable.z

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Business Insider. (2024, Dec. 1). I have an AI boyfriend. We chat all day long.

Brookings Institution. (2025, July 2). What happens when AI chatbots replace real human connection.

De Freitas, J., et al. (2025). AI Companions Reduce Loneliness. Journal of Consumer Research.

European Broadcasting Union (via Reuters). (2025, Oct. 21). AI assistants make widespread errors about the news.

Feng, Y., et al. (2025). Effectiveness of AI-Driven Conversational Agents in Reducing Mental Health Symptoms. Journal of Medical Internet Research.

Guardian (Weale, S.). (2025, Feb. 26). UK universities warned to ‘stress-test’ assessments as 92% of students use AI.

LiveScience. (2025, Nov.). Chinese company’s humanoid robot moves so smoothly they cut it open onstage.

OECD. (2023). Emerging governance of generative AI in education.

OpenAI. (2025, Sept. 5). Why language models hallucinate.

Pew Research Center. (2025, Jan. 15). Share of teens using ChatGPT for schoolwork doubled to 26%.

SCMP. (2025, Nov.). The big reveal: Xpeng founder unzips humanoid robot to prove it’s not human.

UNESCO. (2023/2025). Guidance for generative AI in education and research.

Weis, A., et al. (2024). Hallucination Rates and Reference Accuracy of ChatGPT and Bard for Systematic Reviews. Journal of Medical Internet Research.

Wired. (2025, June 26). My couples retreat with 3 AI chatbots and the humans who love them.

Comment