Southeast Asia AI Productivity: Why the Payoff Rises or Falls with Learning, Not Just Spend

Published

Modified

AI investment pays off in Southeast Asia only when paired with real workforce learning Training, workflow redesign, and governance turn tools into measurable productivity and wage gains Shift budgets from hardware to people so diffusion is broad, fast, and inclusive

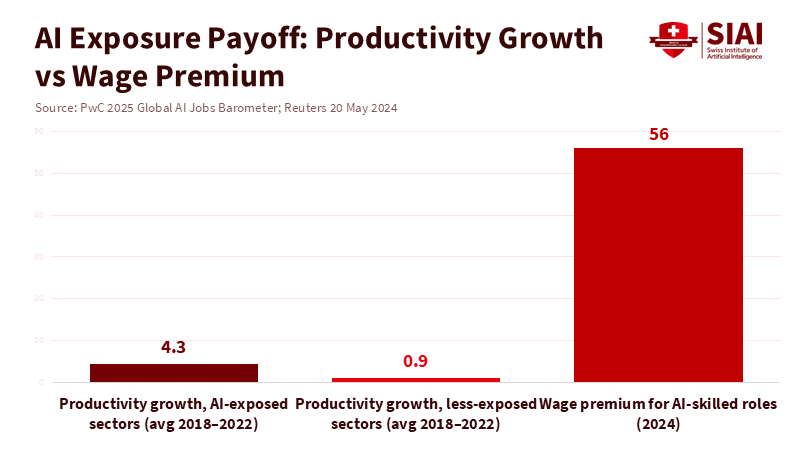

The most revealing number in today’s AI conversation isn’t a billion-dollar investment or a flashy compute benchmark. It’s the fourfold difference in productivity growth between sectors most exposed to AI and those least exposed. This is coupled with a 56% wage premium for workers in AI-skilled roles. These indicators are based on PwC’s analysis of nearly a billion job ads and firm outcomes. They highlight a clear point: where AI is used effectively, output per worker increases quickly, and wages rise. Where it isn’t applied well, the opposite happens. In Southeast Asia, the investment narrative is significant, with tens of billions of dollars poured into data centers and cloud regions, leading the region's digital economy back to double-digit growth. However, the returns depend on people, processes, and time. The main argument of this essay is straightforward: Southeast Asia's AI productivity will depend on how quickly schools, companies, and government bodies can transform AI from mere tools into daily habits.

Southeast Asia AI productivity starts with human learning

We know AI can boost output within firms. An extensive study of customer support agents found that access to a generative AI assistant increased average productivity by about 14%, with the most significant gains—about a third—among the least experienced workers. This scenario is common in many Southeast Asian service jobs, which often have high turnover, steep learning curves, and significant skill gaps. Studies of software illustrate the same point. In a controlled task, developers using GitHub Copilot completed coding nearly 56% faster than the control group. This efficiency increase adds up over a year of sprints and fixes. The mechanism isn’t magical. AI captures practical know-how from skilled workers and offers it to novices during their work, shortening the learning curve and spreading best practices. In short, Southeast Asia's AI productivity improves when learning speeds up.

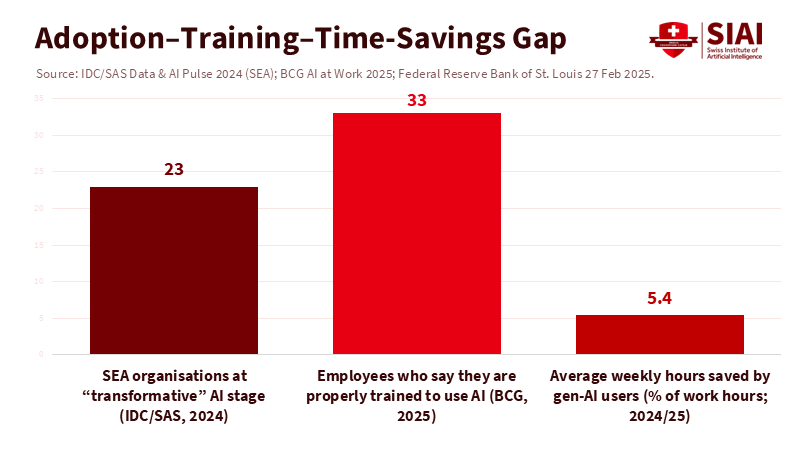

The challenge is that learning never happens for free. Surveys show many employees save significant time using AI, but only a small percentage receive formal training on how to apply it. A global workplace poll found that users save about an hour per day on average, but only 1 in 4 had received training. Another study from the St. Louis Fed measured time savings of 5.4% of weekly hours for users—about 2 hours per week for a standard 40-hour schedule. Training older or less tech-savvy workers requires intentional effort. In a UK pilot, simple permissions and a few hours of coaching significantly increased AI usage among late-career women in lower-income jobs—a lesson with clear implications for Southeast Asia's diverse labor markets. Unless leaders allocate time and money for this human ramp-up, AI tools will remain unused, and productivity will stagnate. Improving Southeast Asia's AI productivity is primarily a management challenge rather than a hardware race.

Southeast Asia AI productivity depends on uneven adoption

Adoption across the region is occurring but remains uneven. According to Google, Temasek, and Bain, over $30 billion was invested in AI infrastructure in Southeast Asia during the first half of 2024, while the broader internet economy returned to double-digit growth. Governments and tech giants are acting quickly: Thailand approved $2.7 billion in funding for data center and cloud investments, while Microsoft committed $1.7 billion to Indonesia, aiming to train 840,000 Indonesians in AI skills as part of a regional goal of 2.5 million. Yet, enterprise readiness lags. An IDC/SAS survey revealed that only 23% of Southeast Asian organizations are at a “transformative” stage of AI use. A separate Deloitte survey shows that executives identify the most significant barriers as talent shortages, risk, and a shaky understanding of the technology. In simple terms, capital is arriving faster than the necessary skills.

There are encouraging signs. Agentic AI—software that connects tasks—might expand quickly as companies turn pilot programs into standard operations. Multiple regional surveys indicate that about two in five firms already use such agents, with most others planning rollouts within the following year. However, relying on averages obscures significant national differences in skills, infrastructure, and digital trust. The World Bank warns that when adoption depends on task structures and complementary skills, the benefits will flow to workers and firms that can adapt to the technology, leaving others behind. The OECD reaches a similar conclusion: AI can boost productivity, but long-term benefits rely on widespread usage, regulations, and inclusivity. This leads to a clear policy implication: to enhance Southeast Asia's AI productivity, leaders must close the “last-mile” gap between large capital expenditures and frontline workers.

Financing Southeast Asia AI productivity: from capex to opex

Much of the AI budget in the region focuses on hardware, cloud credits, and vendor proofs of concept. The larger returns lie in the operating budget: training time, workflow redesign, risk management, and change processes. This is where many digital programs fall short. Research shows that 70% of significant transformations exceed their original budget—often because they underestimate the organizational effort involved. The empirical evidence on potential payoff is becoming clearer. PwC’s analysis links AI exposure to faster productivity growth and increased revenue per employee. MIT’s call center experiment, along with the Copilot RCT, provides estimates of the gains firms can expect from well-planned adoption. These figures support a shift in perspective: view training and change as investments with measurable results, not just expenditures to cut.

What could effective operating expenses look like? Start with hours saved. If typical users can save around 5% of their weekly time now—and even more on repetitive knowledge tasks—modest adoption across a 10,000-person company can yield thousands of hours freed weekly. Add small-group coaching, workflow standards, and secure model access, and the time savings can accelerate further. In practice, measurable benefits often appear quickly once tools are integrated: Bain’s Southeast Asia analysis notes that many firms see returns within 12 months. On the public side, targeted skills programs can increase returns on private investments. The ILO’s new initiative to deliver digital skills in ASEAN’s construction sector serves as a valuable model for employer-linked training. Microsoft’s large-scale upskilling efforts in Indonesia aim in the same direction. A practical rule emerges: if we cannot identify scheduled training hours and a redesigned workflow, we should expect Southeast Asia's AI productivity to disappoint, regardless of how much computing power we acquire.

Governing Southeast Asia AI productivity for the long run

Sustained productivity improvements require policies that facilitate diffusion while minimizing harm. The World Bank’s work in East Asia and the Pacific highlights that skill policies, mobility, taxes, and social protections will determine whether technology promotes inclusion or inequality. In education, this means expanding from pilot programs to overarching curricula that include training in prompting, verification, and tool selection from upper secondary levels onward. In TVET systems, this involves establishing AI labs linked to local businesses and introducing stackable micro-credentials that align with real jobs. In universities, it means enforcing strict academic integrity policies while still allowing supervised AI use for drafting, coding, and analysis.

For administrators, procurement should focus on outcomes rather than just acquiring licenses. Contracts can stipulate vendor-funded training hours per license, workflow templates, and measurable time savings at six- and twelve-month intervals. Ministries could collaborate to establish regional standards for model safety, data governance, and interoperability, thereby reducing costs and risks for smaller institutions. The OECD's caution regarding uneven diffusion, combined with PwC's findings on wage premiums, supports reskilling subsidies tied to wages and mobility assistance, ensuring benefits don't just concentrate in already-advantaged areas. Lastly, infrastructure policy must remain practical. Reports on Thailand’s data center expansion and coverage of Indonesia’s hyperscale investments illustrate this point. Data centers are vital, but their social return depends on practical skills and open access. Otherwise, these power-hungry assets could remain unused while schools and clinics lack the necessary tools. The goal of governance is steady, inclusive, measurable, and sustainable improvement in Southeast Asia's AI productivity.

The key figures introduced at the beginning of this essay—greater productivity growth and a 56% wage premium in AI-focused roles—are not inevitable; they are invitations to action. They demonstrate what can be achieved when tools meet trained individuals and when work processes are restructured. In Southeast Asia, capital is flowing in through national data center initiatives and hyperscaler commitments for training. Research results consistently indicate that productivity increases most rapidly when newcomers learn quickly and when managers allocate resources for change. The region now faces a clear choice. It can view AI as a competition for hardware and settle for narrow benefits concentrated in a few companies and cities. Alternatively, it can prioritize people—teachers, nurses, programmers, clerks—and invest in the time, coaching, and standards necessary for practical tool usage. If it chooses the latter path, Southeast Asia's AI productivity could become a strong driver of the next growth cycle: compounding, inclusive, and evident in both paychecks and profits.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Adecco Group. (2024, October 17). AI saves workers an average of one hour each day (press release).

AP News. (2024, April 30). Microsoft will invest $1.7 billion in AI and cloud infrastructure in Indonesia.

Bain & Company; Google; Temasek. (2024). economy SEA 2024. Key highlights page.

BCG. (2024, June 26). AI at Work in 2024: Friend and Foe.

Deloitte. (2025). Generative AI in Asia Pacific (regional pulse).

IDC (commissioned by SAS). (2024, November 6). IDC Data & AI Pulse: Asia Pacific 2024 (SEA cut).

ILO. (2025, June 26). New initiative to boost green and digital skills in ASEAN construction.

McKinsey & Company. (2023, April 11). Why most digital transformations fail—and how to flip the odds.

NBER (Brynjolfsson, Li, & Raymond). (2023). Generative AI at Work (Working Paper No. 31161).

OECD. (2024). The impact of artificial intelligence on productivity, distribution and growth.

PwC. (2025, June 3/26). Global AI Jobs Barometer press materials (productivity growth; 56% wage premium).

Reuters. (2025, March 17). Thailand approves $2.7 billion of investments in data centres and cloud services.

St. Louis Fed. (2025, February 27). The Impact of Generative AI on Work Productivity.

The Conversation (hosted via University of Melbourne). (2025, August 14/15). Does AI really boost productivity at work? Research shows gains don’t come cheap or easy.

World Bank. (2025, June 2). Future Jobs: Robots, Artificial Intelligence, and Digital Platforms in East Asia and Pacific; (2025, August 5) How new technologies are reshaping work in East Asia and Pacific.