AI Chatfishing, AI Companions, and the Consent Gap: Why Disclosure Decides the Harm

Published

Modified

AI chatfishing hides bots in dating, removing consent and raising risks Declared AI companions can help, but still need strict guardrails Require clear disclosure, platform accountability, and education to close the consent gap

When a machine can pass for a person 70 percent of the time, the burden of proof shifts. In a 2025 study, which served as a modern Turing test, judges who chatted simultaneously with a human and a large language model identified the AI as the human 73 percent of the time. This study, conducted by [research institution], used [specific AI model] to demonstrate the rapid advancement of AI technology. This is not a simple trick; it marks the point where “Are you real?” stops being a fair defense. Move this capability into online dating, and the stakes increase rapidly. A wrong guess can lead to emotional, financial, and sometimes physical costs. AI chatfishing, which involves using AI to impersonate a human in romantic chat, thrives when the line between person and program is hard to define and is clear that it is blurred. To protect intimacy in the digital age, we need a straightforward rule that both the law and platforms can support: disclose whenever it’s a bot, every time, and make dishonesty costly for those who create the deception.

AI Chatfishing versus AI Companions: Consent, Expectations, and Incentives

AI chatfishing and AI companions are not the same. Both operate on the same technology and can appear warm, attentive, and even sweetly awkward. Yet, the key difference lies in consent. With AI companions, users opt in; they choose a system that openly simulates care. In contrast, AI chatfishing lures someone into a conversation that appears authentic but isn't. This difference alters expectations, power dynamics, and potential harm. It also changes incentives. Companion apps focus on satisfaction and retention by helping users feel better. Deceptive actors prioritize gaining resources—money, images, time, or attention—while concealing their methods. When the true nature of the speaker is hidden, consent is absent, and the risks range from broken trust to fraud and abuse. The distinction is moral, legal, and practical: disclosure turns a trick into a tool, while the lack of disclosure turns a tool into a trap. The rule must be as clear as the chat window itself.

Consequently, clear disclosure is essential. Europe has established a foundation. The EU AI Act requires that people be informed when they interact with a chatbot so that they can make an informed choice; this responsibility helps maintain trust. In October 2025, California took further steps. A new state law requires “companion chatbots” to state that they are not human, incorporate protections for minors, and submit public safety reports—including data on crisis referrals—so parents, educators, and regulators can see what occurs on a broader scale. Suppose a reasonable user might mistake a chatbot for a human. In that case, the system must disclose this, and that reminder must recur for minors. These rules outline a global standard the intimate internet needs: when software communicates like a person in contexts that matter, it must identify itself, and platforms must ensure that identity is unmistakable.

The Growing Role of AI in Dating and Why AI Chatfishing Thrives

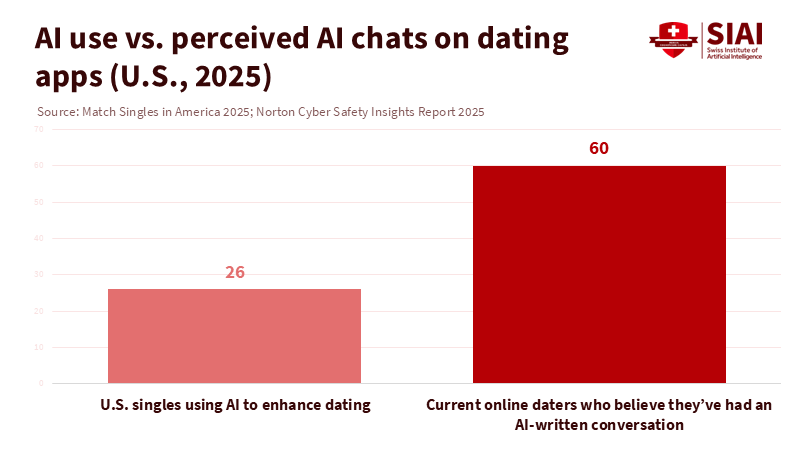

Usage is increasing rapidly. Match Group’s 2025 Singles in America study, conducted with Kinsey Institute researchers, reveals that about one in four U.S. singles now uses AI to improve some aspect of dating, with the highest growth among Gen Z. A separate 2025 Norton survey shows that six in ten online daters believe they have had at least one conversation written by AI. Major outlets have noted this shift as platforms introduce AI helpers to enhance profiles and generate conversation starters. At the same time, users adopt tools to improve matches and avoid awkward starts. Meanwhile, role-play and companion platforms keep millions engaged for extended periods—indicating that conversational AI is not just a novelty but a new form of social software. This scale is significant: the more common AI chat becomes, the easier it is for AI chatfishing to blend in unnoticed.

Detection is also challenging in practice. The same Turing-style study that raised concerns explains why: when models adopt a believable persona—young, witty, and adept online—they not only imitate grammar; they also replicate timing, tone, and empathy in ways that feel human. Our own psychology contributes to this, too. We enter new chats with hope and confirmation bias, wanting to see the best. A university lab study in 2024 found that non-experts only identified AI-generated text about 53 percent of the time under test conditions, barely above random guessing. Platforms are working on this. Bumble’s “Deception Detector” utilizes machine learning to identify and block fake, spam, and scam profiles; the company claims it can catch the majority of such accounts before they reach users. This is helpful, but it remains a platform promise rather than a guarantee, and deceptive actors adapt. The combination of increasing usage, human misjudgment, and imperfect filters creates a persistent space where AI chatfishing can thrive.

Why AI Companions Are Different and Still Risky for the Public Good

Stating that an entity is artificial changes the ethics. AI companions acknowledge their software status, and users can exit at any time. Many people report real benefits: practice for socially anxious daters, relief during grief, a space to express feelings, or prompts for self-reflection. A widely read first-person essay in 2025 describes how paying for an AI boyfriend after a painful breakup revealed that the tool provided steady emotional support—listening, prompting, and encouragement—enough to help the writer regain confidence in life. Public radio coverage reinforces this idea: for some, companions serve as a bridge back to human connection rather than a replacement. The role of AI companions in providing emotional support is significant and should be acknowledged.

However, companions still influence the public space. If millions spend hours practicing conversations with tireless software, their tolerance for messy human interaction may decline. Suppose teenagers learn early scripts about consent, boundaries, and empathy from systems trained on patterns. In that case, those scripts may carry into classrooms and dorms. New research warns that some systems can mirror unhealthy behaviors or blur sexual boundaries when protections are weak, especially for minors. The potential negative influence of AI companions on social skills is a concern that needs to be addressed.

Additionally, because many companion platforms frequently update their models and policies, the “personality” users rely on can change suddenly, undermining relationships and trust. The social consequences develop slowly and collectively: norms change, affecting not just individual experiences. This is why disclosure is vital, but not enough. We need age-appropriate designs, limitations on prolonged sessions, and protocols that encourage vulnerable users to seek human help when conversations become troubling. These requirements fit a declared, opt-in product; they cannot be enforced on hidden AI chatfishing.

Policy and Practice: A Disclosure-First Standard for the Intimate Internet

We should shift from asking whether AI chatfishing or AI companions are “worse” in the abstract and instead align rules with actual harm. Start with a disclosure-first standard for any intimate or semi-intimate setting, including dating apps, private marketplaces, and companion platforms. Suppose a reasonable person might mistake the speaker for a human. In that case, the system must say it is not and repeat this cue during more extended conversations. This rule should be enforced at the platform level, where logs, models, and interface choices can interact effectively. Align with existing frameworks: adopt the EU transparency baseline and the new California requirements to ensure users see consistent messages across regions. Importantly, notices should be placed inside the chat box, not in footers or terms links. The goal is to make identity part of the discussion, not a hidden puzzle for users already managing emotional and relational risks.

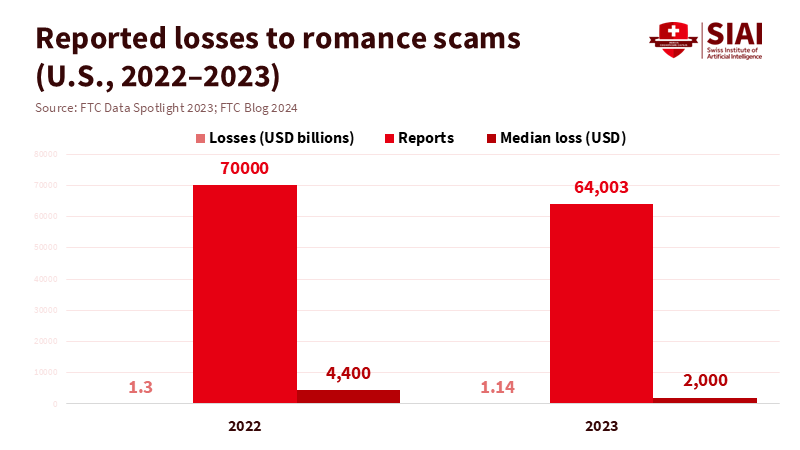

Markets also need incentives to combat deception that disclosure alone cannot address. Romance scammers extracted at least $1.14 billion from U.S. consumers in 2023, with a median reported loss of $2,000 per person; the actual toll is likely higher because many victims do not report. Platforms should face consequences when they ignore clear signals: rapid message frequency from new accounts, reuse of scripted templates, or coordination among fraud rings across apps. Regulators can facilitate this by measuring meaningful outcomes. They should publish standardized safety dashboards on bot takedown rates, time to block after a user’s first report, and median losses recovered. Require annual third-party audits to investigate evasion tactics and false positives. California’s initiative to mandate public reporting on crisis referrals is a positive step; similar disclosures on deception would help turn safety from a slogan into a measurable factor. For declared companions, require opt-in for minors, along with additional reminders and session limits, as California law requires. These are not theoretical ideals; they are practical measures aimed at reducing the space where AI chatfishing can profit.

Education Closes the Loop

K-12 digital citizenship programs should go beyond phishing links to focus on interpersonal authenticity: how to identify AI chatfishing, how to ask for identity confirmation during a chat without feeling ashamed, and how to exit quickly if something feels off. Colleges should update conduct codes and reporting systems to include AI-related harassment and deception, particularly when students use models to manipulate others. Procurement teams can act now by choosing tools that display identity labels by default in the chat interface and offer a one-tap option for verified human support. Faculty can model best practices in office-hour chatbots and course communities by using clear badges and periodic reminders. These small, visible actions help students adopt a norm: in close conversations, being honest about who—and what—we are is the foundation of care.

The question of which is “worse” has a practical answer. Hidden AI in romance is worse because it strips away consent, invites fraud, and exploits intimacy for profit. Declared AI companions can still pose risks, but the harms are limited by choice and design. Suppose we want a healthier future for dating and connection. In that case, we should create regulations that make disclosure seamless and deceit costly. We must educate people, especially teenagers and young adults, on what an “AI disclosure” looks like and why it is essential. Finally, we should focus on measuring outcomes rather than just announcing features, so platforms that prioritize user protection succeed while those that enable AI chatfishing fall short. The experiments have already demonstrated that machines can impersonate us; the real challenge now is whether we can remain genuine ourselves.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

BusinessWire. (2024, February 6). Bumble Inc. launches Deception Detector™: An AI-powered shield against spam, scam, and fake profiles.

European Commission. (n.d.). AI Act — transparency obligations.

Federal Trade Commission. (2024, February 13). Love stinks—when a scammer is involved.

Harper’s Bazaar. (2025, January 24). How I learned to stop worrying and love the bot.

Jones, C. R., & Bergen, B. K. (2025). Large language models pass the Turing test. arXiv preprint.

LegiScan. (2025). California SB 243 — Companion chatbots (enrolled text).

Match Group & The Kinsey Institute. (2025, June 10). 14th Annual Singles in America study.

Penn State University. (2024, May 14). Q&A: The increasing difficulty of detecting AI versus human.

Scientific American. (2025, October). The rise of AI “chatfishing” in online dating poses a modern Turing test.

Skadden, Arps. (2025, October 13). New California “companion chatbot” law: Disclosure, safety protocol, and reporting requirements.

The Washington Post. (2025, July 3). How AI is impacting online dating and apps.

WHYY. (2025, May 7). Will AI replace human connection?

Wired. (2025, August). Character.AI pivots to AI entertainment; 20M monthly users.