Building the Third AI Stack: An Airbus-Style Playbook for Public AI Cooperation

Published

Modified

Build a third AI stack for education Adopt an Airbus-style consortium for procurement Prioritize teacher time-savings, multilingual access, and audited safety

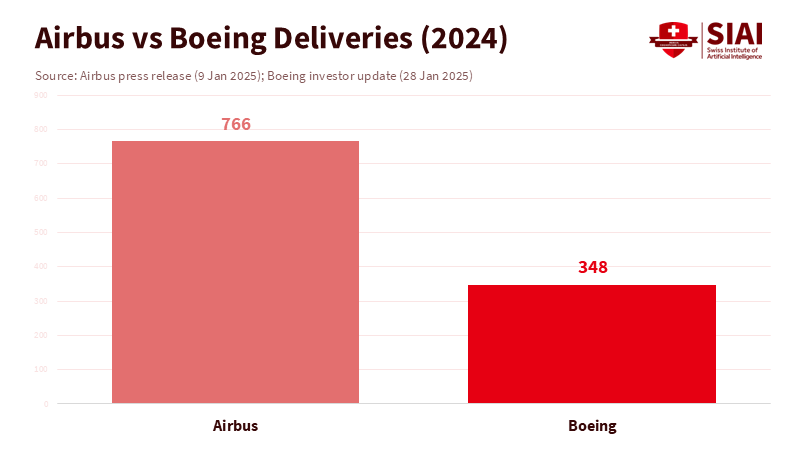

A single number highlights the stakes: in 2024, Airbus delivered 766 jetliners, which is more than twice Boeing's 348. This marks a significant advantage for a European consortium over an American company that once seemed unbeatable. The lesson isn't about airplanes; it's about how countries can combine resources, industrial policies, and standards to shape a critical market. Education is at a similar turning point. If we want safe, affordable, multilingual AI for classrooms, research, and public services, we need the third AI stack. This stack would be a collaborative layer of compute, data, and safety infrastructure that works alongside corporate platforms and open-source communities. Europe is starting this stack with €7 billion for shared supercomputing, while the United States is launching NAIRR to provide compute and datasets to researchers. Together, these initiatives outline a path similar to Airbus's AI approach. The opportunity is limited. Compute and model scales are rapidly increasing. Without coordinated efforts, the gap between what schools need and what private stacks offer will grow.

Why the third AI stack matters now

The third AI stack is not just a future possibility, but a pressing need in the present. Its importance is underscored by the current market dynamics and the increasing concentration of advanced AI in the hands of a few.

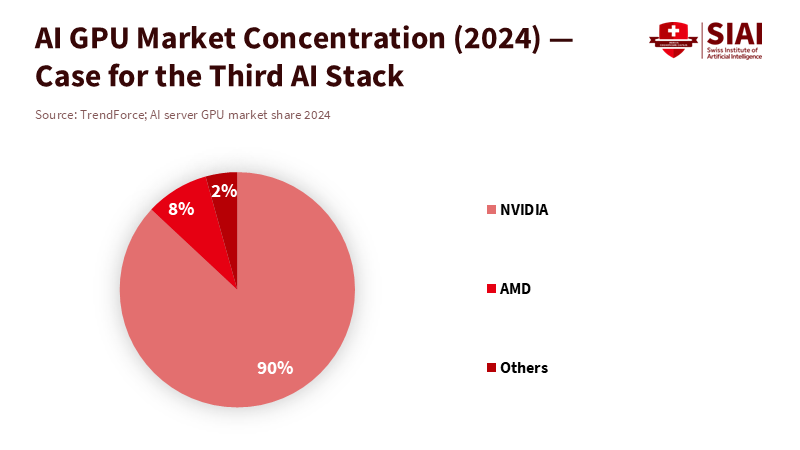

The market for advanced AI is concentrating where it counts most: accelerator hardware and the software that keeps users dependent on it. Analysts estimate that training costs for cutting-edge systems have increased by four to five times annually since 2010. The latest compute-intensive runs have exceeded 10^26 floating-point operations. TrendForce reports that, across all types of AI server accelerators, one vendor holds a significant market share, nearing 90 percent in GPU sales alone. This isn't a critique of success; it's a warning about potential bottlenecks and the erosion of bargaining power. When compute, essential frameworks, and curated data reside within a few proprietary stacks, public-interest applications—like multilingual tutoring, teacher planning, and assessment research—get sidelined or priced out. A third AI stack would provide public and cooperative infrastructure to ensure basic access to compute, data protection that protects privacy, and safety evaluations. Without it, education systems will struggle, buying isolated solutions while missing the chance to influence foundational resources.

The policy framework for this third layer is already forming. The EU's AI Act took effect on August 1, 2024, with general-purpose obligations gradually implemented throughout 2025 and high-risk rules to follow. Simultaneously, the OECD's AI Principles—which many jurisdictions now follow—offer a common language for human-centered, trustworthy AI. Regulation alone can't create capacity, but it clarifies responsibilities and reduces uncertainty. When we combine guidelines with pooled resources—common compute, linked data spaces, and shared testing—we create a model for an industry that meets public needs while scaling globally. For schools and universities, this means reliable access to tools that match curriculum, languages, and community values, rather than only seeing systems that prioritize advertising or sales.

An Airbus-style consortium for public AI

Airbus began in 1970 as a Franco-German-UK-Spanish consortium to challenge a dominant player. It didn't succeed through protectionism alone; it pooled R&D risks, standardized interfaces, and coordinated procurement with long-term goals. The results are precise: after facing challenges such as the pandemic and the 737 MAX crisis, Airbus has led global deliveries for 6 years in a row, delivering 766 aircraft in 2024. While no analogy is perfect, the political economy is relevant. What once seemed like a fixed duopoly was transformed by a patient coalition that used shared financing and common standards to accelerate progress. A third AI stack can follow this model: a transatlantic, and eventually global, consortium that networks compute, curates open datasets, and establishes safety tests with independent labs, which collectively provide affordable solutions for public users.

Elements of that consortium already exist. Europe's EuroHPC Joint Undertaking has a budget of about €7 billion to deploy and connect supercomputers across member states. It is now establishing "AI Factories" in different countries to host fine-tuning, inference, and evaluation workloads. In the United States, the National AI Research Resource (NAIRR) pilot began in January 2024, involving 10 federal agencies and over two dozen private and nonprofit partners to provide advanced computing, datasets, models, and training to researchers and educators. Meanwhile, an international network of AI Safety Institutes is beginning to coordinate evaluation methods and share results. If we bring these efforts together under a governance charter focused on education and science, the Airbus analogy could shift from a mere metaphor to a practical plan.

Financing the third AI stack: pooled compute, open data, shared safety

Financing is crucial. The cost of training next-generation models is approaching $1 billion, and infrastructure plans require multi-year commitments. Public budgets can't—and shouldn't—compete dollar-for-dollar with large tech companies, but they can leverage their buying power. Three actions stand out. First, extend EuroHPC-style pooled procurement to create a joint window for education compute, ensuring a set amount of GPU hours for universities, vocational programs, and school districts, with reserved capacity for teacher resources. Second, expand NAIRR into a standing fund with matched contributions from foundations and industry, linked to open licensing for models below a certain capability threshold and protecting access to sensitive datasets above that threshold. Third, formalize the International Network of AI Safety Institutes as the neutral testing ground for models intended for public education, with evaluations focusing on pedagogy, bias, and child safety. These aren't ambitious goals; they extend existing programs.

The regulatory schedule supports this approach. The phased obligations of the EU AI Act for general-purpose and high-risk systems create clear targets for vendors. The OECD's compute frameworks provide governments with a guide to plan capacity along three dimensions: availability and use, effectiveness, and resilience. From the supply side, the market for accelerators is growing rapidly; one forecast predicts AI data-center chips could surpass $200 billion by 2025. As capacity increases, public purchasers should negotiate pricing that favors educational use, exchanging predictability for volume—similar to how Airbus-era launch aid traded capital for long-term orders within WTO rules. The aim isn't to choose winners; it's to ensure that the third AI stack exists and remains affordable.

Open data is the second pillar. Education can't rely on data scraped from the web, which often fails to represent classrooms, vocational training, and non-English-speaking learners. Horizon Europe and Digital Europe are already funding structured data spaces; these should expand to include multilingual educational data, incorporating consent, age-appropriate safeguards, and tracking of data sources. Curated datasets for lesson plans, assessment items, and classroom discussions—licensed for research and public services—could enable smaller models to perform effectively on tasks that matter in schools. The UNESCO Recommendation on AI ethics, accepted by all 194 member states, addresses rights and equity. The third AI stack needs a data governance component that translates these principles into practical rules for generating, auditing, and deleting student data.

Safety standards need to be measurable, not just theoretical. The emerging network of AI Safety Institutes—from the UK to the U.S.—has started publishing pre-deployment evaluations and building shared risk taxonomies. Education regulators can build on this work by adding specific tests for problems such as incorrect citations, harmful stereotypes in feedback, or unsafe experimental suggestions in lab simulations. The goal isn't to certify "safe AI," but to create a system of ongoing evaluation linked to deployment. This means schools would adopt only models that pass basic audits, and providers would commit to retesting after significant updates. The third stack would incorporate red-teaming sandboxes and make evaluation results available to parents and teachers in clear language, turning safety into a common resource.

From cooperation to classroom impact

The Airbus analogy matters most when it benefits teachers on Monday mornings. Evidence is growing that well-guided generative tools can save time. In England's first large-scale trial, teachers using ChatGPT with a brief guide reduced planning time by about 31 percent while maintaining quality. The OECD's latest TALIS survey shows that one in three teachers in participating systems already use AI at work, with higher adoption rates in Singapore and the UAE. These are early signs, not guarantees, but they indicate where public value lies: planning, differentiation, formative feedback, and translation across languages and reading levels. Suppose the third AI stack lowers the cost of these tasks and implements safeguards. In that case, the advantages will multiply across millions of classrooms.

The policy initiatives are concrete. Ministries and districts can contract for "educator-first" model hosting on AI Factory sites that ensure data residency, fund small multilingual models refined on licensed curriculum content, and develop secure portals that give teachers access without dealing with consumer terms of service. Universities can reserve NAIRR allocations for education departments and labs, speeding up rigorous trials that assess learning improvements and bias reduction, rather than just user satisfaction. Safety institutes can hold annual "education evaluations" in which vendors are tested against shared benchmarks developed by teachers and child development experts. None of this requires building a national chatbot; it requires cooperation across borders, budgets, and standards so that classroom-ready AI is a guaranteed resource, not an optional extra.

Critics may argue that public-private cooperation could reinforce existing players or that governments may act too slowly for an industry that doubles its computing every few quarters. Both points have merit. However, the Airbus story shows that coordinated buyers can influence supply while enhancing safety and interoperability. The pace of change isn't as mismatched as it seems. EuroHPC is setting up AI-focused sites; NAIRR is bringing in partners; the International Network of AI Safety Institutes is synchronizing tests. The crucial missing element is a clear education mandate that unites these efforts for classroom applications and establishes shared goals: hours saved, reduced inequalities, measurable improvements in reading and numeracy, and clear audits of model behavior in school environments.

The alternative is stagnation. Suppose we let the market set its own direction. In that case, education will be stuck with sporadic pilots and individual licenses that rarely expand. If we focus solely on regulation, we will create paperwork without the capacity to implement it. The third AI stack represents a middle ground: a collaborative infrastructure that minimizes risks, lowers costs, and empowers educators. Airbus didn't eliminate Boeing; it compelled a duopoly to compete on quality and efficiency. A public AI consortium won't replace private stacks; it will drive them to compete based on public value.

Let's return to the opening figure: an international consortium delivered 766 aircraft last year, outpacing its rival's total by more than double because countries chose to share risk, align standards, and collaborate over decades. Education needs this same long-term perspective for AI. Build the third AI stack now: secure compute resources for teaching and research on EuroHPC and NAIRR, create multilingual, consented data spaces for pedagogy, and establish safety evaluation as an ongoing public service. Then enter into large-scale contracts so that every teacher and learner can access trustworthy AI in their language, aligned with their curriculum, and compliant with their laws. This isn't just about catching the latest trends; it's about establishing the foundational framework that lowers costs, builds trust, and allows schools to choose what works best. Airbus demonstrates that practical cooperation can accelerate progress. The following two years will determine whether education is in control or merely trying to keep up.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

AP News. (2025, January). Boeing's aircraft deliveries and orders in 2024 reflect the company's rough year. Retrieved from AP News.

Cirium. (2025, January). Shaking out the Airbus and Boeing 2024 delivery numbers. Retrieved from Cirium ThoughtCloud.

Digital Strategy, European Commission. (2024–2025). AI Act: Regulatory framework and application timeline. Retrieved from European Commission.

Education Endowment Foundation. (2024, December). Teachers using ChatGPT can cut planning time by 31%. Retrieved from EEF. EuroHPC Joint Undertaking. (2021–2027). Discover EuroHPC JU and budget overview. Retrieved from EuroHPC.

European Commission. (2024). AI Factories—Shaping Europe's digital future. Retrieved from European Commission.

OECD. (2023). A blueprint for building national compute capacity for AI. Retrieved from OECD Digital Economy Papers.

OECD. (2024). Artificial intelligence, data and competition. Retrieved from OECD.

OECD. (2025). Results from TALIS 2024. Retrieved from OECD.

OECD.AI. (2019–2024). OECD AI Principles and adherents. Retrieved from OECD.AI.

Reuters. (2025, January). Airbus keeps top spot with 766 jet deliveries in 2024. Retrieved from Reuters.

Simple Flying. (2025, October). Underdog story: How Airbus became part of the planemaking duopoly. Retrieved from Simple Flying.

Stanford HAI. (2025). AI Index 2025—Economy chapter. Retrieved from Stanford HAI.

TrendForce. (2024, July). NVIDIA's market share in AI servers and accelerators. Retrieved from TrendForce.

U.S. National Science Foundation. (2024, January). Democratizing the future of AI R&D: NAIRR pilot launch. Retrieved from NSF.

U.S. Department of Commerce / NIST. (2024, November). Launch of the International Network of AI Safety Institutes. Retrieved from NIST.

Epoch AI. (2024–2025). Training compute trends and model thresholds. Retrieved from Epoch AI.