AI-Assisted Teaching Is the Reform, Not the Threat

Published

Modified

AI-assisted teaching is the reform, not the threat Shift assessment from answer-hunting to reasoning and disclosure Train every teacher and set simple norms so AI boosts equity and learning

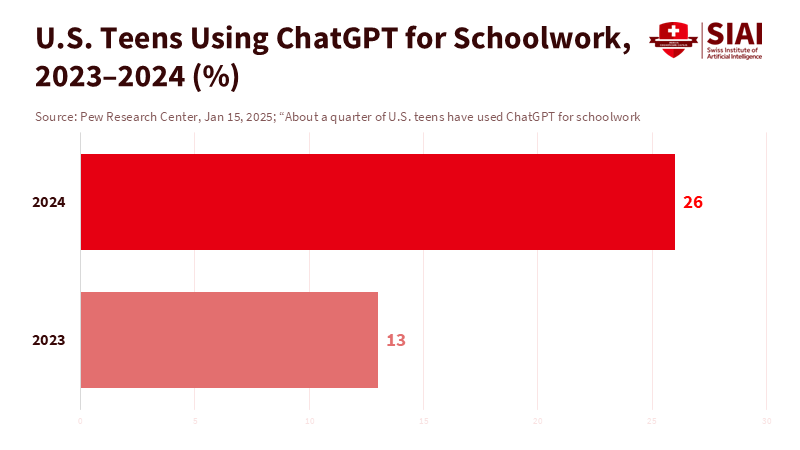

A single statistic should reframe the debate: in 2024, one in four U.S. teenagers used ChatGPT for schoolwork, a figure double that of 2023. The trend is steep, and it is still early. Most teens have not yet used it. But the growth is clear. AI is now a typical study habit for a significant minority, rather than a rare case. We can try to block it or oversee it. Or we can accept a simple truth: technology has already changed classrooms. The question is not how to fix the tool; it’s how to adjust teaching around it. This is at the heart of AI-assisted teaching. We need to set expectations that foster authentic learning, even when answers are just a prompt away. The goal is both straightforward and challenging: create classrooms where the easy path is not the learning path. The easy path should only help students do the hard work more effectively.

Reframing the problem: AI-assisted teaching replaces answer-hunting with thinking

The introduction of chatbots has revealed a problem with assessments rather than a cheating issue. We have asked students to gather facts and repackage them. Machines can do that much faster. AI-assisted teaching requires a shift in instruction. Tasks must encourage students to evaluate sources, compare different perspectives, test claims, and show their reasoning within time constraints. This is not an abstract ideal; it is the only way to keep learning central when AI provides fluent but shallow text. Surveys indicate that teens feel AI is suitable for research but not for writing essays or solving math problems. This instinct is healthy. We should respond with assignments that demand human judgment and original thinking. When a prompt can yield an outline, the assignment must require selecting, defending, and revising that outline using course concepts and cited evidence. Here, the tool becomes the starting point, not the endpoint.

The policy context has also moved in this direction. UNESCO’s global guidance encourages systems to focus on human agency, build teacher capacity, and create age-appropriate guidelines. This advice matters because teaching—not software—determines whether AI is beneficial or harmful. Countries and districts are beginning to respond. Training is increasing rapidly, but it is uneven and incomplete. In the U.S., the proportion of districts offering AI training jumped from about one quarter in fall 2023 to nearly one half in fall 2024, with plans indicating further growth. Teacher surveys show that usage is still concentrated in planning and content drafting, not in deep data use for learning. This is a story about capacity, not fate. Suppose we invest in teachers and redesign assessments. In that case, AI-assisted teaching can turn a potential risk into a tool for greater rigor.

What the data already shows: productivity gains and learning effects

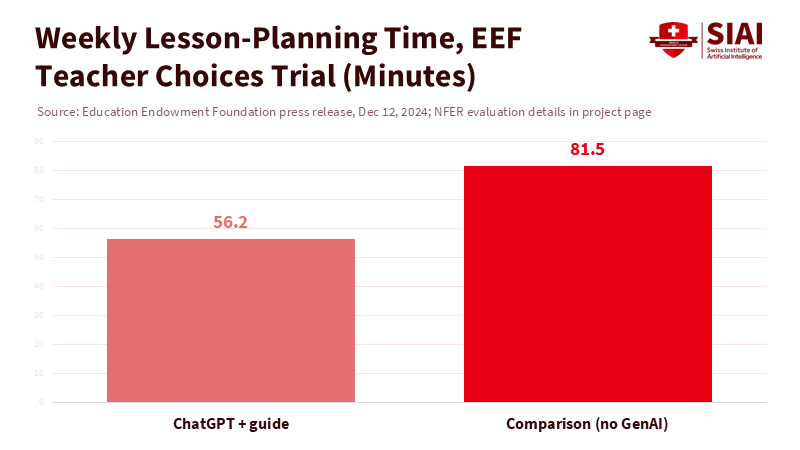

The early evidence regarding teacher workload is clear. When teachers use well-guided prompts, lesson preparation time decreases without affecting quality. A large trial in England found that providing a simple guide along with ChatGPT reduced planning time by about a third. That level of gain is rare in education. It frees up hours for feedback, tutoring, and class discussions—elements of teaching that machines cannot replicate. U.S. surveys reflect this trend. Many teachers report using AI weekly, and those who do so regularly save several hours each week. These savings are not just conveniences; they create time for instruction that focuses on analysis and argument rather than recall. AI-assisted teaching starts by giving teachers back their time.

Learning effects are beginning to show, especially in writing. Randomized trials indicate that structured AI feedback can enhance revision quality for college students and language learners. Improvements happen when students use AI to identify problems and refine drafts, rather than skipping the drafting process altogether. This is the actionable takeaway for classrooms: make AI a critic, not a ghostwriter. When the task requires students to summarize complex readings, compare arguments, and defend a claim with quotations, AI can offer style advice or highlight weak topic sentences. Students must still engage in critical thinking. This approach aligns with AI-assisted teaching principles. The machine excels at providing rapid feedback and minor edits. At the same time, the student tackles tasks that require human reasoning, judgment, and decision-making.

The adoption gap: training, equity, and the new baseline for rigor

Adoption varies across systems and subjects. The OECD’s recent international teacher survey shows that, on average, about one in three teachers use AI, with leaders like Singapore and the UAE approaching three-quarters. In other areas, teacher usage remains below one in five. Within countries, use is primarily focused on lesson drafting and content adaptation, with limited application for formative analytics. This pattern is predictable and solvable. Training drives usage. Where teachers receive structured professional development, adoption and confidence grow. Equity must receive the same attention. If only well-resourced schools incorporate AI-assisted teaching, the existing gaps in feedback and enrichment will widen. The policy expectation should be clear: every teacher should understand how to use AI to create better lesson plans, develop richer examples, and design assessments that value reasoning over searching.

Student use is already prevalent. Global student surveys in 2024 revealed high rates of AI usage for academic support, and national snapshots confirm this trend. In the U.S., teen use of ChatGPT for schoolwork doubled in a year. Studies in the UK report that the majority use AI for assistance with essays or explanations. At the same time, students express concerns that AI might undermine study habits if misused. This tension should shape policy decisions. Banning and detection will not scale; teaching and designing must. Schools should clarify norms for acceptable uses of brainstorming, outlining, and language support; disclosure rules; and penalties for presenting AI-generated text as original work. Most importantly, we must raise the rigor of assignments. When tasks require live problem-solving, oral defenses, and iterative feedback on drafts, quick answers hold little value. AI-assisted teaching redirects student energy back to learning.

What to change now: curriculum, assessment, and teacher craft

Curriculum should include AI as a critical literacy. Students need to learn prompt design, source verification, bias detection, and the distinction between fluent language and genuine reasoning. This is not an optional unit; it belongs in core subjects. In writing courses, AI can model alternative thesis frameworks and illustrate counterarguments. In science, it can suggest experimental variations and help design data tables. In language classes, it can provide feedback focused on form while teachers emphasize meaning and interaction. The system's role is to assist; the student's role is to create. Institutions should also adopt standard disclosure policies so students can indicate where and how they used AI. When rules are straightforward and public, misuse decreases and AI-assisted teaching becomes standard practice rather than a loophole. Thoughtful national guidance already points in this direction; local leaders should implement it promptly.

Assessment must shift from recall to reasoning. This means more supervised, classroom-based writing, more oral defenses, and more multi-step tasks that require judgment at each stage. It also involves using AI to create better rubrics and examples. Teachers can ask AI to draft three sample answers—basic, proficient, and advanced—and then refine them to meet standards. Students learn what quality looks like and why it matters. Districts should update honor codes to include AI disclosure and provide clear examples of allowed and prohibited uses. Training remains crucial. As district surveys show, when leaders invest in ongoing professional learning, teachers’ use of AI becomes safer and more effective. We need the same investment that accompanied the transition from chalkboards to projectors to learning management systems—only faster. That is what AI-assisted teaching requires.

Anticipating the critiques—and answering them with design

Critique one argues that AI undermines originality. It can do so if assignments prioritize speed over thought. The solution is not to ban tools but to redesign assignments. When tasks demand unique evidence from class experiments, local data, or in-person observations, generic outputs will not meet expectations. Trials in writing support this point. AI feedback enhances revision quality when students write and then revise. It offers little support when students skip the draft. The solution lies in design, not in fear. We can establish process checkpoints, require annotated drafts, and include reflection as part of the grading. The outcome is more writing, not less, with AI serving as a coach. That is AI-assisted teaching in action.

Critique two warns that AI could worsen inequity. It might, if only some teachers and students knew how to use it effectively. However, policy can bridge the gap. Provide device access and high-quality AI tools in classrooms. Train all teachers, not just volunteers. Share prompt banks, model lessons, and example tasks created within districts. Current international and national guidelines emphasize user-focused methods and teacher development as key elements for safe AI adoption. Systems that prioritize training report higher usage and greater confidence. Equity is not complex; it is about resources, standards, and time. If we build the necessary supports, AI-assisted teaching can help close gaps by providing all students with quick feedback and more opportunities to engage in real thinking.

We should revisit that initial statistic and consider it carefully. A quarter of teens using ChatGPT for schoolwork is not, in itself, a crisis. It is a signal. This signal indicates that students are already studying in an environment where humans and machines coexist. The only real risk is pretending otherwise. If we improve our teaching—if we elevate the expectations for tasks, normalize disclosure, train teachers widely, and incorporate AI literacy into core subjects—we can keep learning at the forefront. We can ensure that speed serves depth. We can enable convenience to support judgment. This is the promise of AI-assisted teaching, and it is also a necessity. The tools will continue to improve. The only way to stay ahead is to teach what they cannot do: reason with evidence, explain under pressure, and adapt ideas to new situations. Let us create classrooms where these skills become the norm. The statistic will keep rising. Our standards should rise even faster.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Education Endowment Foundation (2024). Teachers using ChatGPT – alongside a guide to support them to use it effectively – can cut lesson planning time by over 30 per cent. (press release, Dec. 12, 2024).

OECD (2025). Teaching for today’s world: Results from TALIS 2024.

Pew Research Center (2025). About a quarter of U.S. teens have used ChatGPT for schoolwork—double the share in 2023. (Jan. 15, 2025).

RAND Corporation (2024). Using Artificial Intelligence Tools in K–12 Classrooms.

RAND Corporation (2025). More Districts Are Training Teachers on Artificial Intelligence.

UNESCO (2023; updated 2025). Guidance for generative AI in education and research.

Zhang, K. (2025). Enhancing Critical Writing Through AI Feedback (randomized controlled trial). Humanities & Social Sciences Communications.