Chatbots Are Not Search: Algorithmic Gatekeeping and Generative AI in Education Policy

Published

Modified

Chatbots replace lists with a single voice, intensifying algorithmic gatekeeping In portal-first markets like Korea, hallucination and narrowed content threaten civic learning Mandate citations, rival answers, list-mode defaults, and independent audits in schools and platforms

Only 6% of people in South Korea go directly to news sites or apps for news. The majority access information through platforms like Naver, Daum, and YouTube. When most of a nation relies on just a few sources for public information, how those sources are designed becomes a civic issue, not just a product feature. This is the essence of algorithmic gatekeeping. In the past, recommendation engines provided lists. Users could click away, search again, or compare sources. Chatbots do more than that. They make selections, condense information, and present it in a single voice. That voice can appear calm but may be misleading. It might "hallucinate." It can introduce bias that seems helpful. If news access shifts to a chatbot interface, the old concerns about search bias become inadequate. We need policies that treat conversational responses as editorial decisions on a large scale. In Korea's portal culture, this change is urgent and has wider implications.

Algorithmic gatekeeping changes the power of defaults

In the past, the main argument for personalization was choice. Lists of links allowed users to retain control. They could type a new query or try a different portal. In chat, however, the default is an answer rather than a list. This answer influences the follow-up question. It creates context and narrows the scope. In a portal-driven market like Korea, where portals are the primary source for news and direct access is uncommon, designing a single default answer carries democratic significance. When a gate provides an answer instead of a direction, the line between curation and opinion becomes unclear. Policymakers should view this not simply as a tech upgrade, but as a change in editorial control with stakes greater than previous debates about search rankings and snippets. If algorithmic gatekeeping once organized information like shelves, it now defines the blurb on the cover. That blurb can be convincing because it appears neutral. However, it is difficult to audit without a clear paper trail.

Korea's news portals reveal both opportunities and dangers. A recent peer-reviewed study comparing personalized and non-personalized feeds on Naver shows that personalization can lower content diversity while increasing source diversity, and that personalized outputs tend to appear more neutral than non-personalized ones. The user's own beliefs did not significantly affect the measured bias. This does not give a free pass. Reduced content diversity can still limit what citizens learn. More sources do not ensure more perspectives. A seemingly "neutral" tone in a single conversational response may hide what has been left out. In effect, algorithmic gatekeeping can seem fair while still limiting the scope of information. The shift from lists to voices amplifies this narrowing, especially for first-time users who rarely click through.

Algorithmic gatekeeping meets hallucination risk

Another key difference between search and chat is the chance for errors. Recommendation engines might surface biased links, but they rarely create false information. Chatbots sometimes do. Research on grounded summarization indicates modest but genuine rates of hallucination for leading models, typically in the low single digits when responses rely on provided sources. Vectara's public leaderboard shows rates around 1-3% for many top systems within this limited task. That may seem small until you consider it across millions of responses each day. These low figures hold in narrow, source-grounded tests. In more open tasks, academic reviews in 2024 found hallucination rates ranging from 28% to as high as 91% across various models and prompts. Some reasoning-focused models also showed spikes, with one major system measuring over 14% in a targeted assessment. The point is clear: errors are a feature of current systems, not isolated bugs. In a chat interface, that risk exists at the public sphere's entrance.

Korea's regulators have begun to treat this as a user-protection issue. In early 2025, the Korea Communications Commission issued guidelines to protect users of generative AI services. These guidelines include risk management responsibilities for high-impact systems. The broader AI Framework Act promotes a risk-based approach and outlines obligations for generative AI and other high-impact uses. Competition authorities are also monitoring platform power and preferential treatment in digital markets. These developments indicate a shift from relaxed platform policies to rules that address the actual impact of algorithmic gatekeeping. If the main way to access news starts to talk, we must ask what it says when it is uncertain, how it cites information, and whether rivals can respond on the same platform. Portals that make chat the default should have responsibilities more akin to broadcasters than bulletin boards.

Algorithmic gatekeeping in a portal-first country

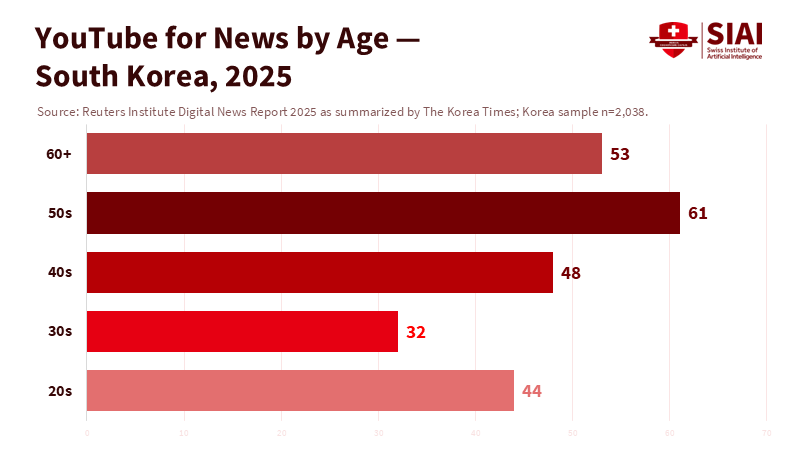

South Korea is a critical case because portals shape user habits more than in many democracies. The Reuters Institute's 2025 country report highlights that portals still have the largest share of news access. A Korea Times summary of the same data emphasizes the extent of intermediation: only 6% of users go directly to news sites or apps. Meanwhile, news avoidance is increasing; a Korea Press Foundation survey found that over 70% of respondents avoid the news, citing perceived political bias as a key reason. In this environment, how first-touch interfaces are designed matters significantly. If a portal transitions from lists to chat, it could result in fewer users clicking through to original sources. This would limit exposure to bylines, corrections, and the editorial differences between news and commentary. It would also complicate educators' efforts to teach source evaluation when the "source" appears as a single, blended answer.

The Korean research on personalized news adds another layer. If personalization on Naver tends to present more neutral content while offering fewer distinct topics, then a constant chat interface could amplify a narrow but calm midpoint. This may reduce polarization at the edges but could also hinder diversity and civic curiosity. Educators need students to recognize differing viewpoints, not just a concise summary. Administrators require media literacy programs that teach students how an answer was created, not just how to verify a statement. Policymakers need transparency not only in training data, but also in the live processes that fetch, rank, cite, and summarize information. In a portal-first system, these decisions will determine whether algorithmic gatekeeping expands or restricts the public's perspective. The shift to chat must include a clear link from evidence to statement, visible at the time of reading, not buried in a help page.

What schools, systems, and regulators should do next

First, schools should emphasize dialog-level source critique. Traditional media literacy teaches students to read articles and evaluate outlets. Chat requires a new skill: tracing claims back through a live answer. Teachers can ask students to expand citations within chat responses and compare answers to at least two linked originals. They can cultivate a habit of using "contrast prompts": ask the same question for two conflicting viewpoints and compare the results. This helps build resistance against the tidy, singular answers that algorithmic gatekeeping often produces. In Korea, where most students interact with news via portals, this approach is essential for civic education.

Second, administrators should set defaults that emphasize source accuracy. If schools implement chat tools, the default option should be "grounded with inline citations" instead of open-ended dialogue. Systems should show a visible uncertainty badge when the model is guessing or when sources differ. Benchmarks are crucial here. Using public metrics like the Vectara HHEM leaderboard helps leaders choose tools with lower hallucination risks for summary tasks. It also enables IT teams to conduct acceptance tests that match local curricula. The aim is not a flawless model, but predictable behavior under known prompts, especially in critical classes like civics and history.

Third, policymakers should ensure chat defaults allow for contestation. A portal that gives default answers should come with a "Right to a Rival Answer." If a user asks about a contested issue, the interface should automatically show a credible opposing viewpoint, linked to its own sources, even if the user does not explicitly request it. Korea's new AI user-protection guidelines and risk-based framework provide opportunities for such regulations. So do competition measures aimed at self-favoring practices. The goal is not to dictate outcomes, but to ensure viewpoint diversity is a standard component of gatekeeper services. Requiring a visible, user-controllable "list mode" alongside chat would also maintain some of the user agency from the search age. These measures are subtle but impactful. They align with user habits rather than countering them.

Finally, auditing must be closer to journalism standards. Academic teams in Korea are already developing datasets and methods to identify media bias across issues. Regulators should fund independent research labs that use these tools to rigorously test portal chats on topics like elections and education. The results should be made public, not just sent to vendors. Additionally, portals should provide "sandbox" APIs to allow civil groups to perform audits without non-disclosure agreements. This approach aligns with Korea's recent steps towards AI governance and adheres to global best practices. In a world dominated by algorithmic gatekeeping, we need more than just transparency reports. We require active, replicated tests that reflect real user experiences on a large scale.

Anticipating the critiques

One critique argues that chat reduces polarization by softening language and eliminating the outrage incentives present in social feeds. There is some validity to this. Personalized feeds on Naver display more neutral coverage and less biased statements compared to non-personalized feeds. However, neutrality in tone does not equate to diversity in content. If chat limits exposure to legitimate but contrasting viewpoints, the public may condense into a narrow middle shaped by model biases and gaps in training data. In education, this can limit opportunities to teach students how to assess conflicting claims. The solution is not to ban chat, but to create an environment that fosters healthy debate. Offering rival answers, clear citations, and prompts for contrast allows discussion to thrive without inciting outrage.

Another critique posits that the hallucination issue is diminishing quickly, suggesting less concern. It is true that in grounded tasks, many leading systems now have low single-digit hallucination rates. However, it is also true that in numerous unconstrained tasks, these rates remain high, and some reasoning-focused models see significant spikes when under pressure. In practice, classroom use falls between these extremes. Students will pose open questions, blend facts with opinions, and explore outside narrow sources. This is why policy should acknowledge the potential for error and create safeguards where it counts: defaulting to citations, displaying uncertainty, and maintaining an option for list-mode. When the gatekeeper provides information, a small rate of error can pose a significant social risk. The solution isn't perfection; it's building a framework that allows users to see, verify, and switch modes as needed.

Lastly, some warn that stricter regulations may hinder innovation. However, Korea's recent policy trends suggest otherwise. Risk-based requirements, user-protection guidelines, and oversight of competition can target potential harms without hindering progress. Clear responsibilities often accelerate adoption by providing confidence to schools and portals to move forward. The alternative—ambiguous liabilities and unclear behaviors—impedes pilot programs and stirs public mistrust. In a portal-first market, trust is the most valuable resource. Guidelines that make algorithmic gatekeeping visible and contestable are not obstacles. They are essential for sustainable growth.

If a nation accesses news through gatekeepers, then the defaults at those gates become a public concern. South Korea illustrates the stakes involved. Portals dominate access. Direct visits are rare. A transition from lists to chat shifts control from ranking to authorship. It also brings the risk of hallucination to the forefront. We cannot view this merely as an upgrade to search. It is algorithmic gatekeeping with a new approach. The response is not to fear chat. It is to tie chat to diversity, source accuracy, and choice. Schools can empower students to demand citations and contrasting views. Administrators can opt for grounded response modes and highlight uncertainty by default. Regulators can mandate rival answers, keep list mode accessible, and fund independent audits. If we take these steps, the new gates can expand the public square instead of constricting it. If we leave this solely to product teams, we risk tidy answers to fewer questions. The critical moment is now. The path forward is clear. We should follow it.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Adel, A. (2025). Can generative AI reliably synthesise literature? Exploring hallucination risks in LLMs. AI & Society. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-025-02406-7

Foundation for Freedom Online. (2025, April 18). South Korea's new AI Framework Act: A balancing act between innovation and regulation. Future of Privacy Forum.

Kim & Chang. (2025, March 7). The Korea Communications Commission issues the Guidelines on the Protection of Users of Generative AI Services.

Korea Press Foundation. (2024). Media users in Korea (news avoidance findings as summarized by RSF). Reporters Without Borders country profile: South Korea.

Korea Times. (2025, June 18). YouTube dominates news consumption among older, conservative Koreans; only 6% access news directly.

Lee, S. Y. (2025). How diverse and politically biased is personalized news compared to non-personalized news? The case of Korea's internet news portals. SAGE Open.

Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. (2025). Digital News Report—South Korea country page.

Vectara. (2024, August 5). HHEM 2.1: A better hallucination detection model and a new leaderboard.

Vectara. (2025). LLM Hallucination Leaderboard

Vectara. (2025, February 24). Why does DeepSeek-R1 hallucinate so much? Yonhap/Global Competition Review. (2025, September 22). KFTC introduces new measures to regulate online players; amends merger guidelines for digital markets.