Skills-First Hiring in the Age of Agentic AI: What Schools Must Do Now

Published

Modified

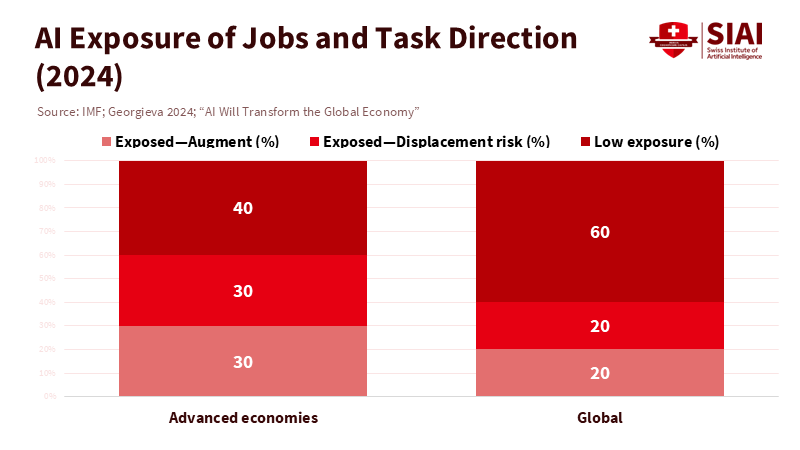

AI now touches most jobs—about 60% in advanced economies Hire for verified skills that complement AI, using portfolios, micro-credentials, and apprenticeships Redesign schooling around agentic AI to widen mobility and prevent exclusion

One number should guide every education and workforce plan this year. In advanced economies, about 60% of jobs are at risk of automation. Roughly half of these jobs could see wage and hiring changes as AI takes over key tasks. The other half may benefit as AI enhances human work. Globally, the figure is close to 40%, but the pressure is most significant in areas focused on knowledge jobs. This isn't just an estimate from a vendor; it's a serious report from the International Monetary Fund. Given this situation, skills-first hiring isn't just a catchphrase. It's the new standard in the labor market. The stakes are clear. If we miss the mark on skills-first hiring, we risk limiting opportunities and sidelining many learners. If we succeed, agentic AI can improve access, accelerate skill development, and help people remain employed as job tasks change. The future hinges on what schools, colleges, and employers do next.

Redefining skills-first hiring for an agentic era

Skills-first hiring isn't a new concept. Employers have been gradually relaxing degree requirements for years. Before the pandemic, nearly half of middle-skill jobs and about a third of high-skill jobs experienced a "degree reset," as listings dropped the bachelor's requirement. However, the practice varies widely. Many companies updated their job ads but kept the old filters in hiring and promotions. In other words, they changed the job advertisement, but not the job structure. Today's agentic AI makes this gap risky. If AI can handle most observable tasks, simple degree checks will overlook what really counts: the ability to work with AI, turn goals into prompts and workflows, and verify results. Skills-first hiring must transform from "no degree necessary" to "proof of specific, valuable skills that support AI."

The demand signal is changing. Surveys show that three out of five workers fear AI will threaten their job security, and many expect wage pressures in their fields. Yet, significant productivity increases are possible. GenAI might generate between $2.6 and $4.4 trillion in value annually. Employers who adopt skills-first hiring can access broader talent pools and more diverse candidates, including women and candidates without degrees. However, the shift from intent to action remains limited. A recent international survey revealed that only about 13% of employers had edited job postings to drop degree and tenure requirements. The risk is evident. If skills-first hiring stalls while automation speeds up, displacement could exceed mobility. This is a design flaw, not an unchangeable rule.

Agentic AI raises the bar by altering what is considered "skilled." The most valuable employees in a skills-first hiring environment will not only code, analyze, or write. They will break down complex problems, manage AI agents, decide when to trust automation, and communicate results to teams and clients. Those skills can be taught, but they don't fit the old credential model. They are ongoing, observable performances. This is why reform is needed in K-12 schools, community colleges, and universities. They must prepare graduates who excel in working with AI, not just consuming it. Otherwise, skills-first hiring will favor those who are already privileged, and the promise of greater access will disappear.

What the evidence says about skills-first hiring and automation risk

The labor market feedback is mixed yet consistent. The World Economic Forum estimates that nearly a quarter of jobs will change by 2027, with 69 million new roles created and 83 million eliminated. The OECD finds that jobs most at risk of automation make up about 27% of employment across member states. Being exposed doesn't guarantee loss, but it does guarantee changes. When exposure is high, skills-first hiring must be faster, fairer, and based on objective evidence. It should require clear demonstrations of skill rather than proxies. This means using performance tasks, portfolios, and on-the-job projects that showcase problem-solving with AI. Hiring teams also need training to interpret this evidence. Without these elements, skills-first hiring will remain just a slogan.

Early employer data show the benefits when this approach succeeds. Skills-first hiring can enlarge candidate pools in ways that support equity and growth. Analyses of LinkedIn's Economic Graph reveal more qualified candidates without degrees when companies filter by skills, resulting in meaningful increases in women's representation. Yet, the practice often lags behind policy. Even as job postings remove some formal requirements, hiring decisions frequently revert to traditional credentials. This misalignment damages trust. Applicants realize the new rules are superficial. Faculty assume that industry won't recognize new learning models. The cycle continues. To break this pattern, schools and employers must collaborate to create skill signals that are hard to fake and easy to validate. Digital micro-credentials that include task evidence are one solution. Paid apprenticeships with public data on completion and wage increases are another.

Educational evidence is advancing, which is significant for hiring. Randomized trials now show that well-designed AI tutors can produce greater learning gains in less time than conventional in-class active learning. Other studies suggest that AI support for tutors enhances student mastery, particularly where tutor skills are lower. These findings are practical. They highlight a way to make skills-first hiring a reality: drastically reduce the time and cost learners incur to develop tangible skills. Suppose every student can access top-quality practice and feedback after school. In that case, the gap between well-resourced and under-resourced learners can narrow. This is a hiring issue, not just an education one. It expands the number of candidates prepared for real work.

Designing schools and colleges for a skills-first hiring world

The main change needed is in the curriculum. Programs should focus on solving problems rather than completing courses. Learners need regular practice that combines subject knowledge with working alongside AI. They should learn to define tasks, choose or develop workflows with agents, verify results, and communicate decisions. Assessments should reveal process evidence. Grading should emphasize clarity, judgment, and handling errors, not just final answers. In this model, skills-first hiring has a dependable dataset. Employers can observe how students use AI to achieve correct and valuable outcomes. Students can demonstrate their progress over time. Faculty can compare groups using shared, public standards—the concept of "job-ready" shifts from a promise to a proof.

Micro-credentials are vital. Europe has adopted a common framework for recognizing short, skill-based learning. This system allows universities and employers to exchange verified qualifications that can cross borders. When these micro-credentials include real work samples, the qualifications become more credible. A badge in "data cleaning and prompt engineering" that comprises code, prompts, logs, and error analysis is more impressive than just a line on a résumé. This is the currency needed for skills-first hiring. It also helps students build on their learning toward degrees without losing progress or support. With agentic AI in the mix, many learners will master job-related workflows more quickly than traditional courses allow. The credentialing system must keep pace.

Practical accessibility is as crucial as design. Evidence shows that AI tutors and AI-assisted tutoring can boost achievement and save time. Schools should implement these tools where time is limited: after school, in homework clubs, and in community centers. The aim is not to replace teachers but to bring practice and feedback closer to where students learn. This is how we raise skill standards. When more learners can complete problem sets with quality guidance, more can try out for jobs. This shifts the dynamics for skills-first hiring. It also changes what hiring managers notice when automated systems evaluate applicant skills.

A policy playbook to slow exclusion and boost mobility

K-12 systems should incorporate agentic AI into core subjects like literacy and numeracy rather than treating it as an add-on. Students should write with AI and then fine-tune it. They should solve math using AI and explain each step. The aim is structured collaboration, not passive dependency. School districts can publish clear guidelines aligned with UNESCO's standards and follow a simple principle: AI can assist your thinking, but you must show you understand. This approach maintains academic integrity while preparing students for environments where AI is common. It also keeps the door open for skills-first hiring, as it fosters habits of documentation and verification.

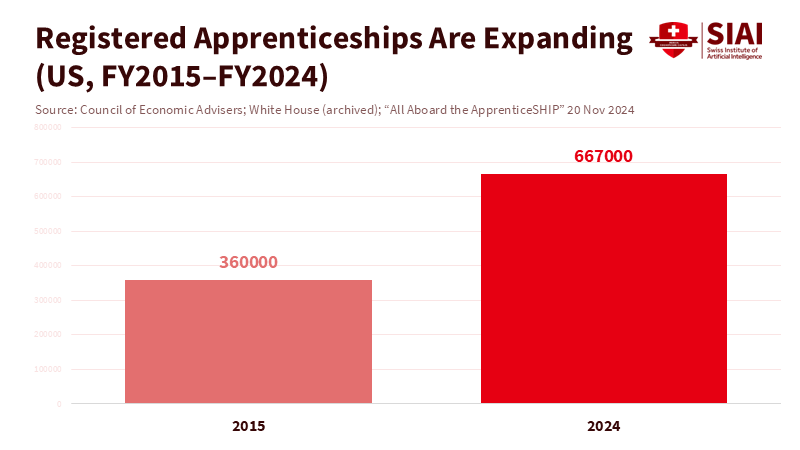

Community colleges should drive skills-first hiring efforts. They are closest to local employers and can quickly refresh programs. The model is straightforward. Assess local task demand. Work with employers to design AI workflows. Teach these workflows along with relevant theory. Evaluate using real work examples. Publish results. Each micro-credential should connect to a role with earning potential, and schools should track placement and earnings. Apprenticeships should cover not only trades but also fields such as data, healthcare, logistics, and green jobs. Statistics show this is achievable. Youth apprenticeships have increased in the United States, both in number and percentage of participants, with tens of thousands added since 2020. A skills-first hiring strategy is more effective when paid learning is common, not the exception.

Universities should restructure general education to focus on enduring skills for an AI-driven world. Skills like reasoning, modeling, evidence interpretation, and communication should be foundational. Every major should have an "AI + X" studio for students to create and defend workflows using AI in their fields. Capstone projects should be public, searchable, and linked in job applications. Career services should shift from résumé enhancement to evidence collection. Meanwhile, registrars should adopt micro-credentials that align with European recognition standards so international students can take verified qualifications home. To maintain their edge in a skills-first hiring market, universities need to produce graduates ready to lead AI-driven teams from day one.

Employers must also play their part. They need to move beyond just revising postings. Clearly define essential skills, publish them, and assess them. Use work samples and job trials early on. Train hiring teams to evaluate portfolios and accurately prompt records. Adjust AI-based screening to prevent old biases from reappearing in new systems. The potential benefits are substantial. Analyses show that skills-first hiring can broaden candidate pools and enhance diversity. It also promotes internal mobility when paired with clear skill frameworks. None of this is kindness. In a market where AI rapidly reshapes tasks, companies that hire for adaptability will outpace those that rely on outdated measures.

An obvious concern is that this vision may be overly optimistic about AI's role in learning and work. We shouldn't overlook the risks. While some randomized trials and field studies highlight significant benefits from AI tutoring, others caution that unsupervised use can hinder learning or widen disparities. The lesson isn't to slow down; it's to create safeguards that keep human judgment central. Clear guidelines on data privacy, model bias, and age-appropriate use are increasingly available. The practical solution in classrooms involves strict alignment with standards, transparent prompts, and visible reasoning. The sensible solution in hiring is to assess skills using real tasks and to publish success metrics by pathway. This ensures that skills-first hiring doesn't become just another empty promise.

A second concern is that skills-first hiring might be a distraction—lots of talk without meaningful change. This concern is valid. Even dedicated companies often revert to prestige screens when urgency arises. The countermeasure is public accountability. Regions can link incentives to concrete results: the number of apprenticeships created, retention rates of non-degree hires, wage increases for first-generation graduates, and the time taken to fill critical roles. Transparency is vital. When results improve, others are likely to follow. When they don't, policies should be adjusted. The same accountability should apply to schools and colleges. If programs claim to deliver job-relevant skills, they should provide evidence and placement data to substantiate those claims.

The final critique is darker. What if the need for human labor collapses in many fields, leaving only a small elite of adaptable workers? That risk is real. However, it is not the most likely outcome in the near future. Significant estimates suggest job changes rather than a full collapse. Tasks are shifting, and productivity is rising with substantial differences across sectors. Even in roles with high exposure, cooperation is possible when people effectively manage AI. Education can improve the odds for collaboration. Hiring based on skills can turn that cooperation into job mobility. Together, these approaches can reduce exclusion and spread the benefits. This is not an idealistic view. It is a practical way to prepare for the uncertainty ahead.

In conclusion, the labor market is entering a phase in which AI systems do more than predict. They start, coordinate, and learn. This change increases the importance of hiring based on skills. The IMF’s exposure figure—60% in advanced economies—should grab our attention. It shows that the risk is widespread and uneven. It also indicates significant opportunities. We can either allow exposure to lead to exclusion, or we can rethink how people learn and how companies hire. The direction is clear. Create curricula that focus on AI collaboration and reasoning. Expand micro-credentials that include evidence of skills. Increase paid apprenticeships. Require hiring teams to evaluate what candidates can actually do. Use AI tutors and AI-supported tutoring where time is limited and feedback is scarce. Share results. Make quick adjustments. If we take these steps, skills-first hiring can become the means through which capable AI enhances human work rather than diminishes it. The wave is already here. Our role is to mold it.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Bastani, H., et al. (2025). Generative AI without guardrails can harm learning. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Burning Glass Institute. (2022). The Emerging Degree Reset.

Business Insider. (2024, Feb.). Companies vowed to hire more workers without college degrees. But a study says they’re not following through.

European Commission. (2024). A European approach to micro-credentials.

IMF. (2024a). AI will transform the global economy. Let’s make sure it benefits humanity. International Monetary Fund Blog.

IMF. (2024b). Melina, G., et al. Gen-AI: Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Work (Staff Discussion Note). International Monetary Fund.

Indeed/YouGov. (2025, Apr.). How to take real action on skills-first hiring. Indeed Lead.

Kestin, G., et al. (2025). AI tutoring outperforms in-class active learning. Scientific Reports.

LinkedIn. (2024). Future of Recruiting 2024. LinkedIn Talent Solutions.

LinkedIn Economic Graph. (2025). Skills-Based Hiring (Report).

Loeb, S., Wang, R. E., Ribeiro, A. T., Robinson, C. D., & Demszky, D. (2024). Tutor CoPilot: A human-AI approach for scaling real-time expertise (Working paper and RCT). Stanford SCALE.

McKinsey & Company. (2023). The economic potential of generative AI: The next productivity frontier.

OECD. (2023). OECD Employment Outlook 2023. Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development.

OECD. (2024a). Using AI in the workplace. Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development.

OECD. (2024b). Lane, M. Who will be the workers most affected by AI? Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development.

Stanford SCALE. (2024a). AI tutoring outperforms active learning (Project page).

U.S. Department of Labor. (2024, Nov.). Trendlines: Youth and women in Registered Apprenticeship. https://www.dol.gov/…/Trendlines_November_2024.html

UNESCO. (2023). Guidance for generative AI in education and research. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

World Economic Forum. (2023). The Future of Jobs Report 2023. World Economic Forum.

Comment