The AI Cognitive Extensions Gap: Why Korea’s Test-Prep Edge Won’t Survive Generative AI

Published

Modified

Korea excels at teen “creative thinking,” but adults lag in adaptive problem solving Generative AI automates routine tasks, so value shifts to AI cognitive extensions—framing, modeling, and auditing Reform exams, classroom routines, and admissions to reward those extensions, or the test-prep edge will fade

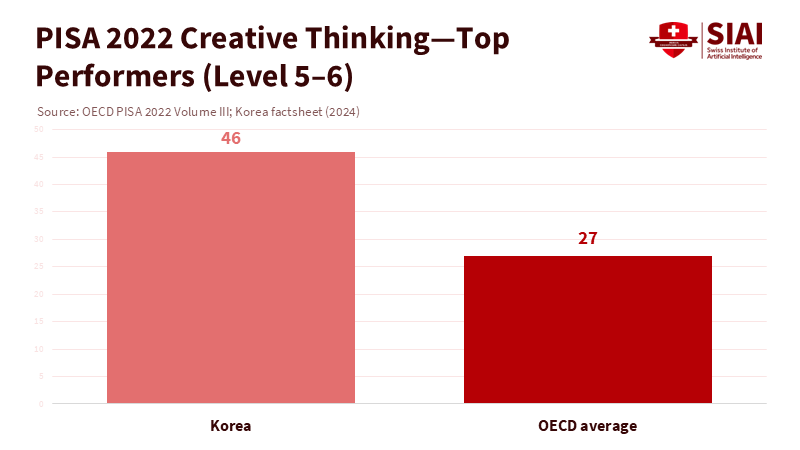

Fifteen-year-olds in Korea excel in “creative thinking.” In 2022, 46% reached the top levels on the OECD test, well above the OECD average of 27%. However, Korean adults struggle with flexible, real-world problem-solving. On the OECD Survey of Adult Skills, 37% score at or below Level 1 in adaptive problem solving, and only 1% reach the top level. This gap is significant. School-age achievements in "little-c" creativity do not translate into adult skills in defining problems, synthesizing evidence, and designing solutions alongside AI. Generative tools speed up this change. Randomized studies show that AI improves routine writing quality by about 18% and reduces time spent by around 40%. Customer support agents solve 14-15% more queries with the help of AI. The real value lies in the human steps before and after automation—what we term AI cognitive extensions: scoping, modeling, critiquing, and integrating across sources. Systems that depend heavily on algorithmic training will struggle, while those that teach AI cognitive extensions will thrive.

AI Cognitive Extensions: Paving the Way for a New Era in Education

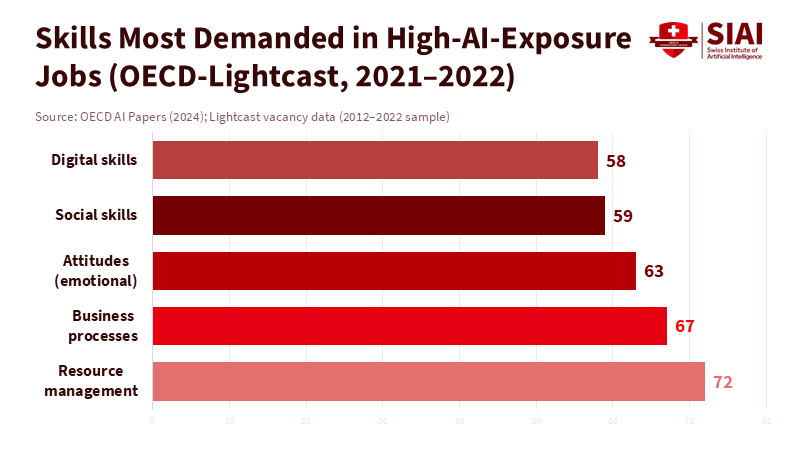

Generative AI now takes on much of the execution work that schools have valued: standard writing, template coding, routine data transformations, and procedural math. In 10 OECD countries, jobs most affected by AI already prioritize management, collaboration, creativity, and communication. Seventy-two percent of high-exposure job postings require management skills, and demand for social and language skills has increased by 7-8 percentage points over the past decade. As tools handle more tasks, employers appreciate the ability to set up the task, break down challenges, evaluate outputs, and communicate decisions across teams. These are AI cognitive extensions. They are not mere soft skills; they represent crucial judgment skills in a world where basic tasks are automated.

Korea has been moving in this direction on paper. The 2022 national curriculum revision, a comprehensive update to the educational framework, aims to cultivate “inclusive and creative individuals with essential skills for the future,” with a focus on uncertainty and student agency. However, policy intent faces cultural challenges. Private after-school tutoring remains nearly universal and is optimized for high-stakes exams. In 2023-2024, participation was around 78-80%, and spending reached record levels—about ₩27-29 trillion—despite a declining student population. The education system still rewards algorithmic speed under exam pressure. This system cannot deliver AI cognitive extensions at scale.

What the Data Says About Korea’s Strengths—and Weak Links

It is tempting to say the system is already succeeding based on high PISA scores in creative thinking. But a closer look reveals the truth. PISA measures' little-c' creativity in familiar contexts for 15-year-olds, assessing the ability to generate and refine ideas within set tasks. It does not evaluate whether graduates can define tasks themselves, combine evidence from different fields, or check an AI's reasoning under uncertainty. The picture changes for adult skills. Korea’s average literacy, numeracy, and adaptive problem-solving in the PIAAC survey fall below OECD averages, with a notably thick lower range in adaptive problem-solving. This discrepancy creates labor-market challenges, such as a mismatch between the skills students possess and the skills employers need, which schools pass to universities and employers. It also highlights the need for AI cognitive extensions.

AI adoption further emphasizes the importance of framing over mere execution. Randomized studies show that generative tools improve output for routine writing and standard customer support, especially for less-experienced workers on templated tasks. Coding experiments with AI pair programmers exhibit similar time savings. Automation reduces the value of algorithmic execution, the very area that cram schools optimize. The emphasis shifts to individuals who can write effective prompts, define evaluation criteria, blend domain knowledge with statistical insight, and justify decisions in uncertain situations. Essentially, AI handles more of the “show your work” aspect, and humans must decide which work to present initially. This is the gap Korea needs to bridge.

Designing an AI Cognitive Extensions Curriculum

The solution lies in the curriculum, not superficial tweaks. Start by teaching students the tasks that AI cannot easily manage: defining problems, selecting evaluation measures, and justifying trade-offs. Make these actions clear. In math and data science, the shift from just solving problems to discussing “model choice and critique”: why choose a logistic link over a hinge loss; the significance of priors; where confounding variables might hide; and how we would identify model drift. In writing, revise assessments from finished essays into decision memos that include evidence maps and counterarguments. In programming, replace bland problem sets with “spec to system” tasks where students must gather requirements, create basic tests, and then use AI to draft and refine while documenting risks. These practices introduce AI cognitive extensions as a series of habits that can be assessed for quality and reproducibility.

Korea can move quickly because its education system already rigorously tracks performance. Substitute some timed, single-answer tests with short, frequent tasks where students submit: a problem frame, an AI-assisted plan, an audit of their model or tool choice, and reflections on their failures. Rubrics should evaluate the clarity of assumptions, the choice of evaluation metrics, and the student’s ability to highlight second-order effects. This approach maintains meritocratic standards while rewarding advanced thinking. National curriculum language that emphasizes adaptable skills allows for such shifts; the challenge is effectively applying those changes in schools still influenced by hagwon culture. Adjusting classroom incentives to promote AI cognitive extensions is essential for turning policy into practice.

The institutional evidence is telling. A selective European program that imported Western, problem-based AI education into Asia found that a large majority of its Asian students struggled to apply theory to open-ended applications and synthesis. This prompted a redesign of admissions and teaching methods. The issue was not a lack of mathematical ability; instead, it highlighted the missing connection between abstract concepts and real-world applications in uncertain situations—the very essence of AI cognitive extensions. While one case can’t replace national data, it shows how quickly high-performing test takers can stumble when tasks change from executing algorithms to creating them. We should view this as a cautionary tale and a guide for improvement.

Accountability That Rewards AI Cognitive Extensions

Assessment must evolve if curricula are going to change. The national exam system offers a straightforward opportunity for reform. Korea’s test reforms have primarily focused on removing “killer questions.” While this may reduce the competition in private tutoring, it does not assess what truly matters. Instead, introduce scored components that cannot be crammed for: scenario briefs with uncertain data, brief oral defenses of plans, and audit notes for an AI-assisted workflow that flag hallucinations, biases, and alignment risks. Assess these using double-masked rubrics and random sampling to ensure fairness and scalability. If the exam rewards AI cognitive extensions, the system will teach them.

The second area for change is teacher practices. Recent studies of curriculum decentralization show that just giving teachers more freedom does not ensure improvements; they need practical tools and shared routines. Provide curated task banks aligned with the national curriculum’s goals, along with examples of problem framing, evaluation design, and AI auditing. Pair this with quick-cycle professional learning that reflects student tasks; teachers should practice writing prompts, setting acceptance criteria, and conducting red-team reviews. When teachers have heavier workloads, AI should assist with routine paperwork to free up time for coaching higher-order skills. This approach makes AI cognitive extensions a real practice rather than just a slogan.

Lastly, align signals in higher education. Universities and employers should favor admissions and hiring practices that look for portfolios showcasing framed problems, annotated code and data notes, and decision documents with clear evaluation criteria. Analysis of Lightcast data across OECD countries shows growing demand for creativity, collaboration, and management in AI-related roles. Suppose universities publish criteria that require these materials. In that case, secondary schools will start teaching them, and this time it will be effective. Building a strong connection between signals and skills is how Korea can maintain its excellence and update its competitive edge.

The headline figures tell different stories: Korea’s teenagers shine in tested creativity, but many adults struggle with adaptive problem-solving in real-world situations. Generative AI sharpens this divide. It automates much of the task's core and shifts value to the beginning and end: the framing at the start and the audit at the end. These edges constitute AI cognitive extensions. They can be taught, assessed fairly, and scaled when exams, classroom activities, and higher education signals support them. Maintain algorithmic fluency; it still has its place. However, do not mistake fast computation under pressure for the ability to define problems, manage uncertainty, and guide tools with sound judgment. The path forward is not to slow down or ban AI in classrooms. Instead, it involves making the human aspects of the work—the parts that guide AI—visible, regular, and graded. If we act now, Korea can turn its early-stage creative strengths into adult capabilities. If we don’t, students who were prepared for yesterday’s challenges will see their advantages fade. The decision—and the opportunity—are ours.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Bae, S.-H. (2024). The cause of institutionalized private tutoring in Korea. Asia Pacific Education Review.

Brynjolfsson, E., Li, D., & Raymond, L. (2025). Generative AI at Work. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 140(2), 889–951.

Brynjolfsson, E., Li, D., & Raymond, L. (2023). Generative AI at Work (NBER Working Paper No. 31161).

Lightcast & OECD. (2024). Artificial intelligence and the changing demand for skills in the labour market. OECD AI Papers.

Noy, S., & Zhang, W. (2023). Experimental evidence on the productivity effects of generative artificial intelligence. Science.

OECD. (2023). PISA 2022 results (Volumes I & II): Korea country notes.

OECD. (2024). PISA 2022 results (Volume III): Creative thinking—Korea factsheet.

OECD. (2024). Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) 2023 Country Note—Korea and GPS Profile: Adaptive problem solving.

Peng, S., et al. (2023). The impact of AI on developer productivity. arXiv:2302.06590.

Seoul/Korean Ministry of Education; Statistics Korea. (2024–2025). Private education expenditures surveys. (News summaries and statistical releases).

SIAI (Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence). (2025). Why SIAI failed 80% of Asian students: A Cognitive, Not Mathematical, Problem. SIAI Memo.

UNESCO. (2023). Guidance for generative AI in education and research.