Markets are happy, but schools in Europe need to be ready

Input

Modified

Europe’s Growth-at-Risk shows a heavy downside, despite upbeat markets High debt and defence needs tighten budgets, squeezing education Tie budgets to GaR triggers, secure funding now, protect teaching time

The euro area owes a lot of money—88.2% of its total economy. Last November, the EURO STOXX 50 reached a high. Usually, those things don't happen together for very long. If Europe still owes a lot while the economy doesn't grow much, bad stuff is more likely to happen. That's why you need to pay attention to Europe Growth-at-Risk. It's not about what's expected to happen; it's about how things are now, which could lead to bad things later. Right now, it looks like things are getting as risky as they were during past crises, even though the markets are doing well. No one's panicking, but they're too relaxed. This is a problem for schools that depend on taxes and stable money markets. The question is: Do we deal with the risks now and fund schools, or wait and pay even more later if things go wrong?

Europe Growth-at-Risk: What It Really Means

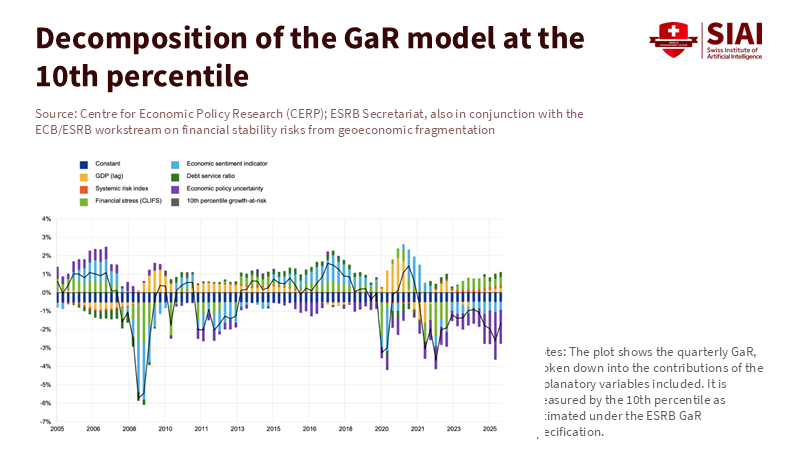

Growth-at-Risk (GaR) looks at how current money and economic conditions affect how the economy might grow in the future. Think of it as a way to see how the economy might react to stress. It doesn't just say what the most likely result next year is, but also how badly the economy could do. The IMF began using this in 2019 to monitor countries. The idea is simple: It looks at things like loan amounts, how much people are borrowing, how shaky things are, and how expensive things are to figure out what could happen. Then the people in charge look at worst-case scenarios to gauge the economy's strength. If bad things seem more likely, they should be careful. Right now, bad outcomes look more likely for the euro area.

Recent estimates for Europe show that things are a bit scary. The risks to the euro area's growth are similar to those during the worst of the financial crisis, the euro crisis, COVID, and the 2022–2023 inflation spike. This doesn't mean a crisis will happen, but it does mean a painful outcome is more than possible, and that there isn't much the government can do. But most forecasts say the economy will grow a bit—about 1.3% in the euro area in 2025—and inflation will cool. The problem is that things seem okay, but there are significant risks. People planning for education should use this like a weather map, not a calendar. Get ready for a storm, even if most days look cloudy but dry.

Why Markets Aren't Worried

If GaR says there's danger, why are European stocks doing so well and loans still easy to get? It's partly because people started retaking risks after the tariff scare in the spring subsided. It's partly because investors think things will be okay, since inflation is easing and interest rates might be cut. And it's partly because investors who aren't banks have been putting money back into risky things, while loan spreads are still tight, even though more people are failing to pay their debts, and lots of loans are being made. The European Central Bank has warned that prices look too high and risky. If something like a political issue, a surprise tax change, or another tariff issue happens, things could change quickly. Prices don't deny there's risk; they just don't reflect it.

Bond markets are also sending mixed signals. Long-term euro area rates are down from their highs, and loan spreads between member states remain narrow. That's good, but it can also hide some problems. Narrow spreads when debts are rising, and there is more money needed, which means that investors trust the government to fix things and don't expect the economy to crash. The ECB's Financial Stability Review says it clearly: things are risky, and some advanced economies might have trouble meeting their debt obligations, which could hurt investor confidence. If spreads widen at the wrong time, it becomes harder to pay for everything, like schools. Education leaders can't control the market, but they can prepare for what might happen.

Debt, Defence, and Education

The euro area's debt has stayed high. It's 88.2% of the economy, and deficits only fell slightly to 3.1% in 2024. Several big members owe even more. France owes over 113%–116% of its economy, Spain owes about 100%, and Germany owes less, in the mid-60s, but it might owe over 80% by 2029 because of investments and defence plans. These aren't just numbers. They affect what can be done when the economy slows, and borrowing becomes more expensive. They also affect how the central and local governments spend money on health, pensions, defence, and education.

The security shock makes things worse. Germany plans to spend €650 billion on defence from 2025 to 2030. France wants to spend 3–3.5% of its economy on defence by 2030, even though it already has high debt and deficits. Markets took this in stride, but there's still pressure on ratings. France's downgrade this autumn showed that it's struggling financially. The IMF warned that Europe's debt could become unstable if it doesn't make some reforms. The math is simple: weak growth, more defence spending, and the cost of an aging population raise spending. If revenues don't rise and things aren't done more efficiently, education suffers. That's how financial risk affects schools: not through a crash, but by slowly cutting budgets, delaying repairs, freezing hiring, and cutting student support.

Action Now: How Education Systems Can Prepare

First, use Europe Growth-at-Risk when planning budgets. The key risk is failing to act until it’s too late. Ministries should set clear GaR-based rules: if five-percentile growth dips for two quarters, funding for education support is triggered. This includes maintenance, salaries, and technology upgrades before borrowing costs spike. The danger is missing this window. Act now when spreads are low. Remember: a 1.3% average with significant risks means preparation, not complacency.

Second, reduce risks in education finance. The main risk is instability from relying on short-term or annually-renewed funds, which may vanish if spreads widen. Use long-term loans for large projects, keep projects ready to launch, and create university funds to buffer against cash shortfalls. The ECB notes that banks are stricter with loans, so school projects may already face hurdles. If credit tightens, governments should temporarily guarantee student loans, but only as a stopgap.

Third, protect education when money is tight. The risk is that financial cuts hurt students and long-term outcomes. Stop nonessential projects before reducing class time. Safeguard early education, teacher development, and tutoring—these investments matter most when the job market is weak. When unemployment rises, offer more scholarships. Keep apprenticeships relevant to local jobs to protect pathways for students entering a tough job market. If budgets drop suddenly, support the most vulnerable to avoid lasting harm.

Fourth, modernize purchasing to do more with less. Combine energy upgrades for schools to lock in lower bills before rates change. Use standard technology platforms and devices to cut replacement costs. Pilot programs for dropout prevention with clear rules. These aren't cost-cutting moves. There are ways to be efficient while managing risk. The goal is to protect learning time and staff when things get tough.

Fifth, teach leaders to understand data. The risk is that leaders may miss signals that require urgent action. Every ministry, district, and university needs people who can read GaR-style reports. They must recognize early warnings, map out responses, and adjust budgets accordingly. Making risk management routine helps keep education on track, preventing unnecessary panic or last-minute scrambles when financial trouble hits.

Addressing Concerns

Some say the markets are right. Stocks are high, spreads are tight, and Europe has handled problems for three years. The Commission and the IMF say growth will be expected. Why act now? Because GaR isn't a prediction of disaster. It's a map of possibilities. The map shows significant risks and little room to maneuver. The ECB warns that prices are high and the financial outlook could hurt confidence. These aren't odd ideas. Waiting for spreads to widen before preparing is like waiting for the siren before buying batteries. By then, prices go up.

Others say debt is okay at current rates, and AI and defence will help the economy grow. Maybe. But France's downgrade shows that things can change. Germany needs its defence and investment plans, but they'll cost money. If tariffs return, export regions will suffer. Banks are strong, but supervisors are planning tests to assess the risk of political shocks. None of this means collapse. It means plans should be ready and funded. Education can't be the thing that gets cut last. It drives growth. Treat it that way when things look risky.

One number shows the point: 88.2%. That's the euro area's debt. On its own, it doesn't predict a crisis. But with record stock prices and GaR estimates rising, it shows a risk. The average outlook for 2025 looks okay, but the worst-case scenarios are not. Education systems have a short time to turn calm markets into safety nets. Connect budget triggers to Europe Growth-at-Risk. Secure funding while spreads are calm. Protect staff and time before making cuts. Teach leaders to read the risk map. The goal isn't to be scared, but to be ready. If we use today's calm to prepare for tomorrow's risks, schools and universities will keep teaching, and students will keep learning.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

European Central Bank. Financial Stability Review (November 2025). Frankfurt am Main.

European Central Bank. “Euro area bank lending survey — October 2025.” Press release and survey tables.

European Central Bank. “Financial stability vulnerabilities remain elevated…” Press release, 26 November 2025.

European Commission. Autumn 2025 Economic Forecast. Brussels.

Eurostat. “Government debt at 88.2% of GDP in euro area.” News release, 21 October 2025.

Financial Times. “Low growth is now Europe’s biggest financial-stability risk,” 16 December 2025.

Financial Times. “Germany approves €50bn in military purchases… part of a €650bn plan,” 18 December 2025.

IMF. Growth-at-Risk: Concept and Application in IMF Country Surveillance. Working Paper, 2019.

IMF. World Economic Outlook, October 2025. Washington, DC.

Le Monde. “Fitch strips France of its ‘double A’ rating,” 13 September 2025.

Reuters. “Germany’s debt to rise above 80% by 2029, stability council says,” 7 October 2025.

Schroders. “European Credit Outlook 2025,” 7 January 2025.

VoxEU/CEPR. “Macro-financial disconnect in the euro area: Assessing tail risks to euro area growth and equities,” 16 December 2025.

Comment