Tariffs Without Truth: Turning the Industrial Policy Arms Race into a Rules-Based Truce

Input

Modified

WTO paralysis spurs tariffs and subsidies—an industrial policy arms race Replace blanket tariffs with evidence-based, sunset countervailing duties Prioritize resilient skills; publish subsidy math to restore trust

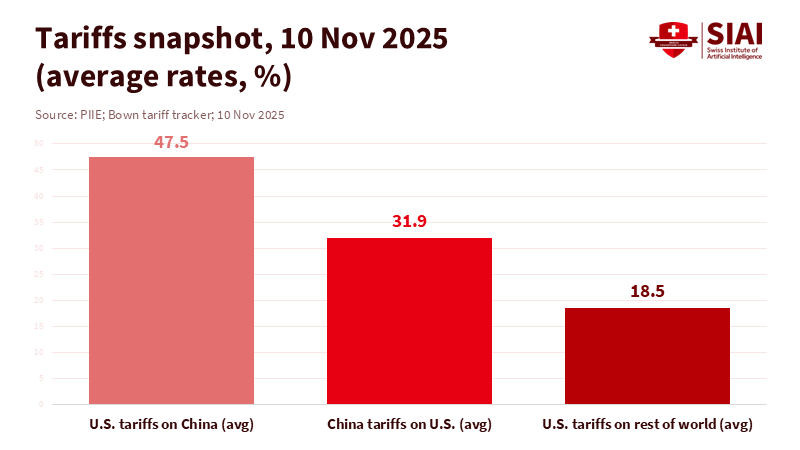

By 2025, the U.S. will slap an average tariff of 47.5% on all Chinese imports. This shows that the trading system isn't keeping power in check; instead, power is running the show. With tariffs popping up, subsidies growing, and the World Trade Organization not really doing much, every economy ministry is basically at war. The industrial policy arms race isn't just a saying anymore; it's real, with tariffs on things like cars and aluminum, and subsidies for semiconductors, batteries, and solar stuff everywhere. This isn't like going back to the 80s. It's a bigger deal: resolving disputes has stopped, strikes are going beyond what's legal, and entire supply chains are leaning toward whoever gets the most aid. Schools need to adjust to this production-focused game. Trade rules do too. The question isn't whether to use tariffs or subsidies, but how to base them on evidence rather than just complaining.

Why this industrial policy fight got so intense

The big problem is with the system itself. Since late 2019, the WTO's appeals body hasn't been functioning because the U.S. has stopped making new appointments. Countries can still win rulings, but if a member loses, they cannot appeal, which cancels out any advantage. With no ref, rules that used to stop subsidy wars—like the Subsidies and Countervailing Measures Agreement—don't matter anymore. Governments have been using their own ways to hit back. Washington has piled on Section 301, Section 232, and new global tariffs; Beijing has filed new WTO complaints and is fighting back; Brussels has launched investigations into subsidies. Each move might make sense on its own, but together they're a mess. Now, complaints are more common than doing what's right, and power—not law—sets the rules.

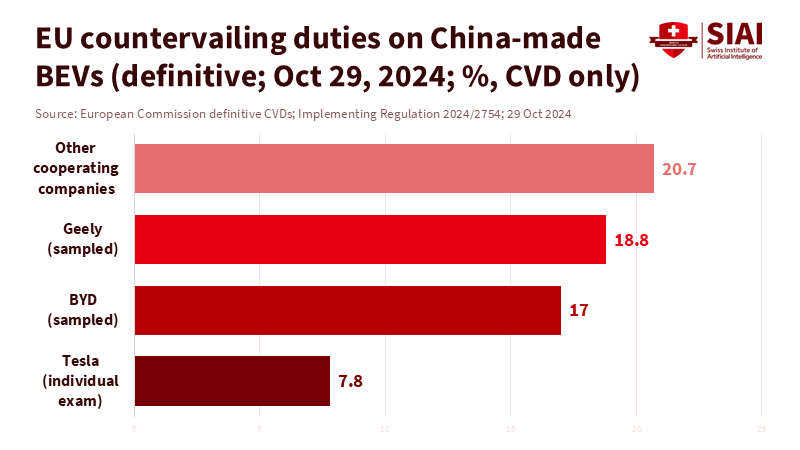

Tariffs get the attention, but subsidies are the foundation. New information from the OECD (the MAGIC database) shows that government support for industries reached its highest level since the financial crisis in 2023, surpassing $108 billion overall. Grants and low-interest loans did much of this, with companies in China getting more out of cheap credit than others. Europe is saying that Chinese electric car batteries get unfair subsidies—and is putting tariffs as high as 40-something percent as a result, which shows how industrial policy now drives trade protection. At the same time, the U.S. has increased its own subsidies through the CHIPS Act and clean-energy tax stuff, while also raising tariffs on a ton of imports from everywhere. It's clear: if there's no one to call the shots, everyone just attacks.

What the numbers say about this industrial policy battle

First, look at tariffs. By November 10, 2025, the Peterson Institute says U.S. tariffs on China are 47.5% across the board. They also say the U.S. average on imports from the rest of the world rose to 18.5% in 2025 due to steps taken on steel, aluminum, and cars. These aren't minor duties to balance out subsidies; they're just big walls. China's tariffs on U.S. goods went up and then down after they made some moves to calm things down mid-year. Overall, it's creating tension rather than fixing things.

Now, about subsidies. The SCM Agreement lets you impose duties only after an investigation proves there's a real subsidy, it's causing real issues, and the duty can't exceed the amount of the subsidy. That's important—and way different from charging everyone extra. Meanwhile, careful estimates of China's public funding suggest it's huge relative to its GDP. One place says support for industries was €221.3 billion (1.73% of GDP) in 2019—which was already high before the push for green tech—and the OECD says companies in China get way better financing deals. This matters because it affects entire supply chains: solar PV production, for example, is now more than 80% in China at every step, with about 95% of new installations built there in 2023–24. When a subsidy changes a whole chain, others don't just lose sales; they lose the ability to learn.

The bad results can be seen in tough sectors. The European Commission's investigation into BEVs says the Chinese supply chain receives unfair subsidies; Brussels then imposed tariffs that could reach the 40s, with talks still underway as Beijing looks into it too. This is what the WTO planned: link solutions to proven subsidy amounts. Yet, because appeals aren't happening, even actions that follow the rules are at risk of being delayed. So there's a fight between law and power. Where law can't close the deal, politics steps in.

Germany's situation shows how issues get bigger. Industrial production has been declining since 2018, and reports from 2024–25 say some of this is due to tougher competition from Chinese producers and the aftershocks of energy price shocks. News stories say the numbers are about 14% below their peak in 2017; official reports show production has been declining for years, and the manufacturing part of GDP is lower than usual, even though the job market is still doing okay. Nothing is because of just one thing. But the mix of high foreign subsidies, weird tariffs, and a broken system for sorting out problems hasn't helped manufacturing in Europe.

Solar shows this really well for teachers who need to teach about skills. Over the past 10 years, over 80% of manufacturing for polysilicon, ingots, wafers, cells, and modules has moved to China, where it has invested $50 billion+ and created 300,000+ jobs along the supply chain. By 2024, China was responsible for about 95% of new PV manufacturing capacity. Europe now relies on Chinese modules for about 9/10 of what it installs, to the point that Italy's first auction for non-Chinese equipment priced power 17% higher. If your training system prepares workers to make PV stuff without a policy to match, you're training them for someone else's factory.

A way out: balance the subsidy, not the country

The task is to replace basic tariffs with steps that balance out real subsidy advantages. The SCM Agreement has the structure: prove the subsidy, measure its size, and limit the duty to that amount. What's missing is good measurements and a working appeals system. For measurements, we now have ways better than before. The OECD's MAGIC database measures grants, tax breaks, and—most importantly—finance deals with low interest rates, which help lower costs. National competition groups also track when imports are cheap, and new places are being built. Together, this can support a Subsidy-for-Tariff Way. If a foreign supplier gains an x-percent subsidy advantage in a product, the importing country can impose a tariff of up to x percent for a limited time, subject to review. This makes solutions fair and sure.

We need something to help while the WTO's Appellate Body is frozen. The MPIA—a backup appeal system used by many WTO members—offers a temporary fix for those who want to use it. Countries not in the MPIA should agree to a similar deal with strict times and public reasoning. The point isn't to punish; it's to make things sure so that companies keep investing based on rules, not chance. Also, any balancing actions should end unless renewed with new data, and they should automatically decrease when the measured subsidy decreases. This creates a way out and pushes governments to be open: if you want lower tariffs, show us what you're doing.

Some say the only real fix is to restore the WTO's appeal mechanism. They're right about the goal, but it'll take time. In the meantime, the fight over industrial policy will keep going unless people join together to measure things. A group of places—like the EU, U.K., Japan, Korea, Canada, Mexico, and others—could agree on how to measure subsidy size in important sectors (EVs, batteries, chips, solar, materials), make quarterly reports, and respect each other's results for quick but limited fixes. That could then turn into regular practice and help fix the trading system.

What educators and leaders should do now

Education leaders can't wait for Geneva. Skills policy needs to match the reality of help that's always there. First, make school programs with two paths that train students for both jobs that rely on subsidies and those that don't. In clean tech, that means training in materials production, component assembly, repair, grid services, and recycling—areas less affected by tariffs. Solar shows this again: setting up modules can be shaky, but installation, operations, and advanced recycling are more reliable jobs even when imports are common. Programs should focus on power electronics, quality control, and methods for getting materials back that work for any tech.

Second, match training to real strengths rather than to what's in the news. If a country has funded a CHIPS group or a battery area, connect school programs to real projects and supplier lists, not just random labels. Where there's proof that imports are relied on—like PV modules in Europe—invest in standards, testing, and skills that improve local activities, no matter where the module comes from. These steps are reasonable in any situation and help people get jobs if trade changes.

Third, teach about trade. Students should know what a balancing duty is, how it differs from a basic tariff, and why fairness is essential. The idea of the SCM Agreement—prove, measure, cap—can be taught in one class and then used for real-world examples. Knowing this helps managers manage supplies, rules, and prices when policy changes occur. This also allows the public: if people know that a fair solution balances the subsidy amount, they can ask for data rather than just listen to talk.

For leaders, the priority is to keep things in check, not to make them worse. Use balancing duties only when the data support them. Don't use basic surcharges that hurt the wrong companies and cause strikes. Show the numbers. Try to settle sector-specific issues by negotiating subsidy limits with check-ups. The EU's handling of EVs—investigation first, solution next—shows this idea, even if the appeals thing makes it more challenging. The U.S. should do things this way and rely less on broad, non-specific tariffs that undermine legitimacy. China can calm markets—and address problems—by ending low-rate financing deals and being more transparent about local support, especially in sectors with excessive production. This doesn't require trust. It requires a standard.

Some might say that measuring is dumb, that subsidies are meant to be hidden, and that politics will always mess things up. But the data is better. The OECD's approach to companies sheds light on finance deals; sector trackers show when production has increased; price and margin studies show the gap policy aims to fill. Even if guesses aren't perfect, they're better than tariffs that don't target the issue and don't let anyone leave. Remember, the SCM Agreement still exists; its rules still say what a good move looks like; and WTO groups still give solid reasons. Countries are using the MPIA to keep a second check where they can, and small deals can cover the rest.

The industrial policy fight won't end with a speech. It'll end when governments stop treating every trade issue as a sin and start targeting specific subsidies for reform. The starting number—U.S. tariffs on China averaging 47.5%—isn't a plan; it's a sign. It shows that politics overtook the rules. The trick is not to eliminate tariffs or subsidies. It's to tie both to logic. Balance the subsidy, not the country. Limit the response. End it unless facts say otherwise. Teachers can get students ready for an economy where policy risk is part of the job; administrators can lead programs toward strong roles; and leaders can rebuild by showing the math. This is how we get back to rules.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Bickenbach, F., et al. “EU Concerns About Chinese Subsidies: What the Evidence Suggests.” Intereconomics (2024).

Bown, C. P. “US-China Trade War Tariffs: An Up-to-Date Chart.” Peterson Institute for International Economics (Nov. 10, 2025).

Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Klimaschutz (BMWK). Annual Economic Report 2025.

CSIS. “The World Trade Organization: The Appellate Body Crisis.” (accessed 2025).

European Commission. “Electric vehicle value chains in China—provisional findings.” Press release (June 11, 2024).

International Energy Agency (IEA). “Solar PV Global Supply Chains—Executive Summary.” (2022–2024 updates).

IEA. “Solar PV.” Data portal (2025 update).

NREL. “Spring 2024 Solar Industry Update.” (June 6, 2024).

OECD. The market implications of industrial subsidies. (May 28, 2025).

OECD. The state of play of industrial subsidies as of 2023 (brief and MAGIC database update). (June 23, 2025).

Reuters. “EU slaps tariffs on Chinese EVs, risking Beijing backlash.” (Oct. 29, 2024).

VoxEU/CEPR. “The recent weakness in the German manufacturing sector.” (Feb. 22, 2025).

WTO. “Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures—legal text.”

WTO. Dispute DS543, United States—Tariff Measures on Certain Goods from China (panel report and appeal status).

WTO/Background. “Subsidies and Countervailing Measures—overview.”

WSJ. “Why Germany Wants a Divorce With China.” (Dec. 15, 2025).

Comment