The Policy Illusion: Why Network Risk Still Rules Peripheral Economies

Input

Modified

Interconnectedness keeps small, open economies exposed despite stronger policies Dollar dominance—88% of FX trades, ~40% invoicing, $100T+ swaps—transmits shocks Fix the plumbing: stress-test FX markets, add regional lines, tighten rules, expand local-currency invoicing

The U.S. dollar is involved in almost 90% of all foreign-exchange deals. That one thing tells you why a small problem in New York can cause big trouble in places like Nairobi or Seoul. Because lots of deals, protections, and payments go through the dollar, any money problems in the U.S. spread to other places. This is especially true for smaller, open countries that rely on trading with the rest of the world. Their companies buy materials and sell their products everywhere. Let's call this emerging market interconnectedness. It’s like the missing piece of the puzzle when we talk about how well these countries can handle crises. Sure, things have gotten better with policies. They're better at controlling inflation, and banks are doing more to protect themselves. But the way countries trade, what money they use, and how they make quick payments still really matter when a crisis hits. If we want to lessen the damage, we need to think of network risk – that is, how connected these countries are – as the main driver of their instability, rather than focusing solely on bad policies. Otherwise, the next time there's a global scare, it'll be another story of careful planning falling apart because of how everything is connected.

Good Policies Are Nice, but Networks Rule

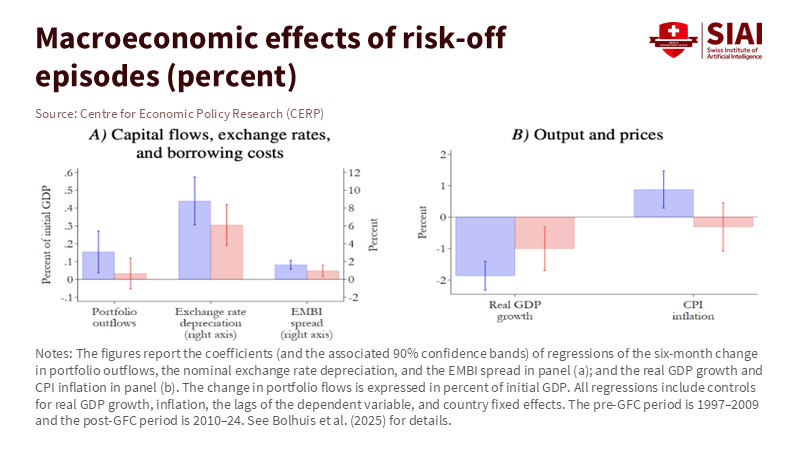

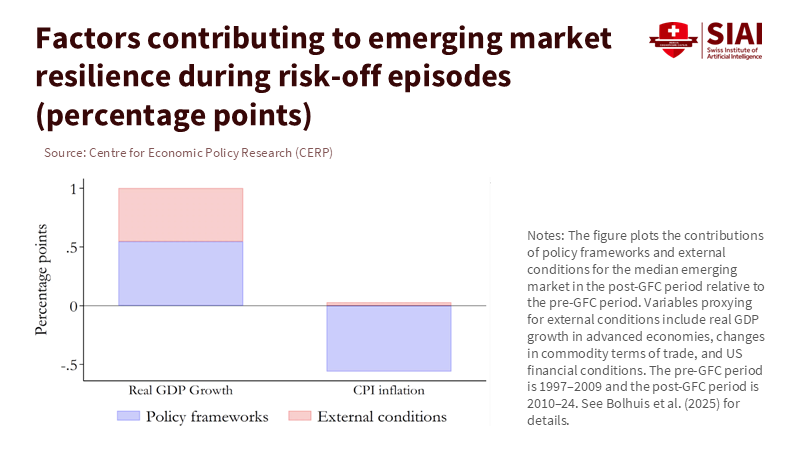

Some people now say that emerging markets don't collapse as easily during global financial scares. They say that better systems – such as setting clear inflation goals, letting exchange rates change more freely, and using stronger tools to control the economy – have helped prevent problems from spreading as much. There's actually some proof that this has worked. Compared to before the 2008 financial crisis, these countries' economies and inflation don't react as strongly to global scares, and their central banks rely more on rules than on firefighting. This improvement in trust is a real achievement. But it's also true that these countries had some luck. The many years of easy money and good global conditions made things easier and gave governments time to make changes. When things get tough again, how safe a country is depends on how it's connected to the world – who lends to it, who buys from it, and what money they use. So, a country's ability to handle crises depends on what it does itself and how it's connected to other countries.

If we focus on how emerging markets are connected, the policy story looks different. The question isn't whether a central bank can do what it's supposed to do on its own. It's whether companies and people can get money to run their businesses, pay their debts in foreign money, and keep trading when it's hard to get dollars worldwide. Even countries with good policies have to rely on global markets, where one currency (the dollar), one interest rate, and one set of organizations are in charge. This explains why two countries with similar rules might suffer differently during the same crisis. The one that trades and borrows more with the big economies usually gets hit harder. Having good policies helps, but being connected to the world sets the limit.

What Reserves, Funding, and Invoicing Data Tell Us

Many emerging markets now have sufficient reserves to be considered safe, and they rely less on foreign capital than they did in the 1990s. That's a real step forward. But there's also been a quiet change in the background. Since the big recession, emerging markets have borrowed more U.S. dollars from other countries, and their government bond prices now move more in line with U.S. financial conditions than they did ten years ago. The data show that the reserve is not enough when the company and bank balance sheets still depend on dollars. Adequate reserves are helpful, but they don't provide a safety net when companies and banks still have a lot of dollar debt – debt they've tried to protect themselves against, but maybe not well enough. The lesson from 2018 onwards is clear: when the dollar strengthens or U.S. conditions tighten, financial conditions in other countries tend to follow suit.

The way trade is invoiced, or billed, keeps this pattern going. Almost half of all global exports are billed in U.S. dollars. This is far more than the U.S.'s share of world trade. This has stayed pretty steady through 2023. Price changes and borrowing costs move through dollar markets, even when countries borrow locally. Also, companies need dollars to handle day-to-day transactions, whether or not they issue dollar bonds. The FX swap/forward market, which enables these payments, is enormous. Over $100 trillion was outstanding at the end of last year, and it depends heavily on the availability of dollars. When that market gets tight, the squeeze spreads quickly through supply chains. This doesn't mean better policy is useless. It just shows why emerging market interconnectedness continues to spread shocks.

Why This Interconnectedness Still Makes Shocks Worse

Take South Korea, for example. Exports account for about 40–45% of its economy, and total trade was nearly 90% of its economy in 2023. This is what you call a small, open economy operating on a large scale. It's a global leader, sure, but it's also strongly connected to the world through electronics, cars, chemicals, and shipping. Even if companies borrow money in their own currency (won), many buy materials and sell their products at prices set in dollars or euros. If U.S. interest rates rise or it becomes harder to obtain dollars, the company's cash flow changes right away. Supplier prepayments, margin calls on protections, and payment schedules all move. In that situation, what matters most isn't the central bank's rules, but whether those protections work, whether the other parties keep lending, and whether banks can price FX swaps without large price discrepancies. That's the network at work.

Two more things explain why the network keeps winning. First, there's about $13 trillion in credit given in currencies other than the U.S. dollar to borrowers outside the U.S., and that number has picked up again this year. These loans are often short- or medium-term, so the risk of needing to renew the loan and the chance to reset the interest rate can come up quickly. Second, the global financial situation moves in tandem, tied to U.S. conditions and to how willing people are to take risks. This situation still explains a lot of the movement in asset prices and money flows. Even with inflation expectations better controlled, this situation sends shocks through wholesale funding (large loans between financial firms), FX protection costs, and investors' decisions to balance risk across different areas. Better domestic rules can lessen the impact; however, they don't disconnect the pipes.

A Plan for Small, Open, and Exposed Economies

The next step is not to give up, but to rethink our priorities. First, we need to see FX transactions as key infrastructure. Supervisors should map and regularly test the domestic FX swap and forward market, including non-bank dealers, to see how they'd handle dollar funding squeezes. Where markets are weak, the government can arrange backstops in advance with clear triggers and price limits to prevent a collapse while limiting the risk of bad behavior. This doesn't mean the government needs to constantly step in, but it does need to be ready to keep the system running when private firms pull back. There's proof that this works. When central bank swap lines were expanded in 2020, pricing problems and gaps narrowed, and dealers kept markets moving. Emerging markets without access to these lines should consider regional pooling and standing repo/swap arrangements with fair pricing.

Second, we need to align the rules governing the financial system with how emerging markets are connected. FX liquidity coverage ratios should be required for banks and, where risks are high, for large companies that use many short-dated derivatives. Supervisors can require standard hedge hygiene (matching maturities to cash cycles; limiting positions without collateral) and transparent reporting of FX margin practices. The goal is not to stop people from protecting themselves. It's to stop that protection from making the shock worse. The IMF’s plan, which combines temporary FX intervention, controls on inflows, and financial controls, can help stabilize conditions without messing up the inflation target. This plan should be used carefully, openly, and with clear exit plans.

From Just Saving Money to Fixing the System: Building Shock Absorbers Outside the Central Bank

Being careful with spending and having a believable monetary policy are still important. But for small, open economies, they're not enough. The government must build shock absorbers into the way trade and payments work. Export credit agencies and development banks can offer low-cost FX hedging for SMEs. Treasury departments can develop mechanisms to manage collateral so payments don't stop during a crisis. Trade groups can push for invoicing in local currency for regional trade while recognizing that the dollar will continue to dominate long-distance trade. None of this replaces careful macro policy. It adds to this by reducing the points at which failure can occur when global risk arises.

Education should connect to the real world. Universities and schools should add global cash-flow planning to the educational module, teaching students how invoicing currency, hedge period, and settlement matter when a funding squeeze hits. Public agencies that help schools can practice currency protection budgeting for imports of journals, lab supplies, and software in dollars. School systems that buy food or fuel on global markets can use natural protections to reduce their costs. For administrators, fixing procurement policy matters more than a new module. For leaders, the test is simple: have you protected the dollar-based parts of your economy? If not, even saving money won't protect you when the next shock comes.

The main point is that, as long as the dollar dominates global transactions and emerging markets are connected through that system, smaller economies will remain exposed to shocks originating far away. Even with domestic achievement in credibility. The way forward is to improve market systems - FX market depth, clear hedging, regional support, and trade that can keep goods moving. That agenda is for all members of the state, from universities to school systems. If we build for the network, not just the textbook, then the next shock will only leave a bruise.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Bank for International Settlements (2025). Annual Report 2025 – II. Financial conditions in a changing global financial system. Basel: BIS.

Bank for International Settlements (2025). Banking statistics and global liquidity indicators at end-September 2025. Basel: BIS.

Bank for International Settlements (2024/2025). Global Liquidity Indicators at end-June 2024. Basel: BIS.

Bank for International Settlements (2022). Triennial Central Bank Survey: OTC foreign exchange turnover in April 2022 and accompanying press release. Basel: BIS.

Bolhuis, M., Grigoli, F., Kolasa, M., Meeks, R., Presbitero, A., & Zhang, Z. (2025). “Emerging market resilience to risk-off shocks: Good luck, but mostly good policies.” VoxEU/CEPR Column, 15 December.

Boz, E., et al. (2025). Patterns of Invoicing Currency in Global Trade in a Fragmenting World Economy. IMF Working Paper WP/25/178. Washington, DC: IMF. (Global invoicing shares through 2023.)

European Central Bank (2018). “Emerging market vulnerabilities – a comparison with previous crises.” ECB Economic Bulletin, Issue 8/2018 (Box). Frankfurt: ECB.

International Monetary Fund (2023). Integrated Policy Framework—Principles for the Use of FX Intervention. Washington, DC: IMF Policy Paper.

International Monetary Fund (2023). Guidance Note on the Liberalization and Management of Capital Flows. Washington, DC: IMF Policy Paper.

International Monetary Fund (2025). Korea in a Changing Global Trade Landscape. Selected Issues Paper. Washington, DC: IMF.

Miranda-Agrippino, S., & Rey, H. (2022). “The Global Financial Cycle.” In Handbook of International Economics, Vol. 6. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

World Bank (2024). World Development Indicators: Exports of goods and services (% of GDP) – Korea, Rep., 2023 observation ≈ 44%. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Yen, J., et al. (2022). “Central Bank Swap Arrangements in the COVID-19 Crisis.” Journal of International Money and Finance.

Comment