Why China’s Got a Problem with Stablecoins

Input

Modified

China blocks stablecoins to guard monetary control Goal: curb capital flight and AML risks; push users to e-CNY/mBridge Ed-tech: use bank rails and e-CNY in China; stablecoins only abroad

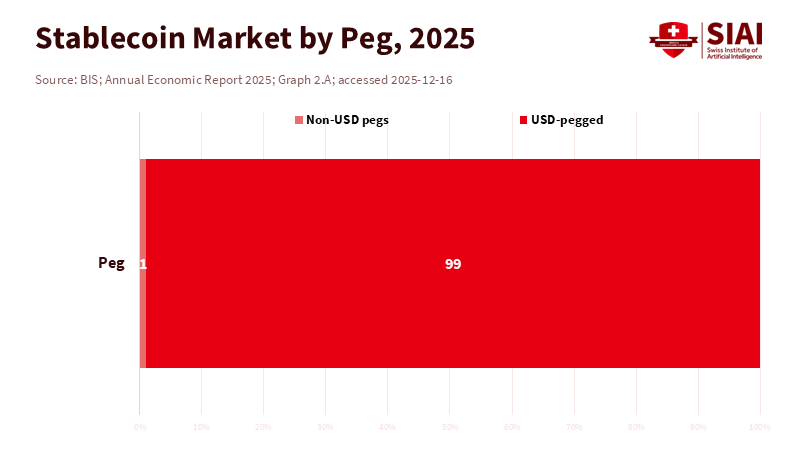

So, here’s the deal: most of the stablecoins out there, like over 99% of them, are tied to the U.S. dollar. By 2025, we saw the number of these stablecoins in use double, reaching around $300 billion, and they were backed mainly by safe assets such as short-term U.S. Treasury bills and bank deposits. Think of it like this: these stablecoins become a new route for payments, but because they’re dollars, they kinda carry the weight of the U.S. legal and political system with them wherever they go. For China, where people are limited to buying only $50,000 in foreign money each year and where the government keeps a close eye on money coming in and out of the country, this isn’t just some neutral payment method. It’s a potential weakness.

Basically, China’s decision to block stablecoins isn’t really about being anti-crypto. It’s about keeping control of their money. By banning them, China is trying to protect itself from what it sees as the dollar taking over, people suddenly moving their money out of the country, and the government losing its grip on how money works inside China. This move aligns with what they’ve been doing for years: banning private cryptocurrencies, building their own digital currency (e-CNY), and creating ways for countries to trade directly (mBridge). You might disagree with their choices, but the reasoning is pretty clear: if money is the way to make policy happen, then the government needs to be in charge.

It’s About Money Control, Not Just Being Anti-Tech

What Beijing’s doing with stablecoins fits a pattern. First, they remind everyone that virtual currencies aren’t legal tender and warn that they’ll crack down on them again. Second, they pressure Hong Kong to hold off on allowing private companies to issue stablecoins, even though Hong Kong is drafting its own stablecoin rules. Third, they push their alternatives: e-CNY for regular people and mBridge for bigger, international transactions.

This isn’t about being scared of new technology. It’s a choice about who gets to be in control. Open, dollar-based tokens issued by private companies are outside the reach of China’s central bank. But a digital currency from the central bank and a government-controlled platform for international payments? Those are under their control. When Chinese regulators talk about risk, what they really mean is losing their ability to prevent money laundering and terrorism financing, sudden movements of money across borders, and the weakening of their own currency, the renminbi.

This stance also makes sense when you look at what’s happening around the world. The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) warned that dollar-tied stablecoins can lead to hidden dollarization and undermine a country’s ability to control its own money, especially in countries that limit how money can move in and out. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has said similar things. So, China’s thinking is pretty straightforward: if the U.S. makes it easy for dollar stablecoins to exist, then those dollar systems get stronger. Letting that into China without any control would be a mistake. Blocking it isn’t about being against new ideas; it’s about protecting their own monetary system.

How Dollars, Money Flight, and Stablecoins Mess with China’s Money Management

The way it works is pretty simple. Stablecoins turn dollars into digital tokens that can be sent instantly, at any time, with minimal middlemen. In countries with shaky currencies, they become a quick way to replace bank deposits. Some experts think that if people continue to adopt dollar-pegged stablecoins as they have been, it could pull hundreds of billions of dollars out of banking systems in developing countries over the next few years. China is worried about this.

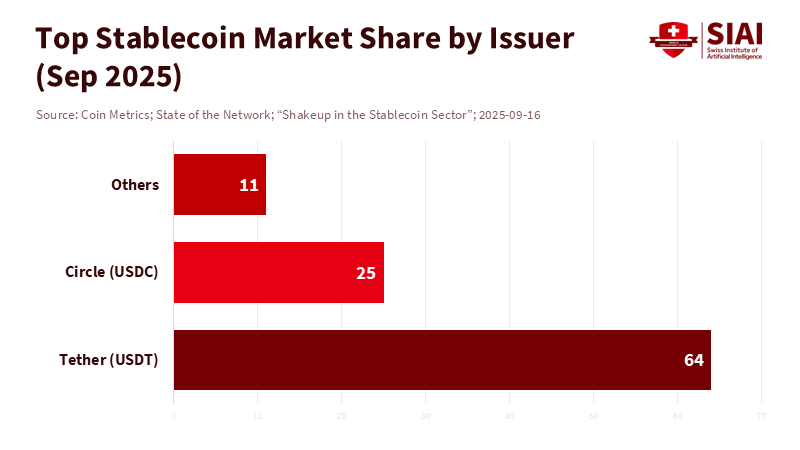

The $50,000 limit on how much foreign money people can buy each year is a key way they control the flow of money out of the country. But cryptocurrency, like Tether, has been used to get around this, making it hard to track money moving through regular banks. Stablecoins make it even easier and faster to get around these limits – and they’re designed to be more dollar-focused.

There’s also the issue of crime. Reports have shown that a lot of illegal activity, like underground banking, online gambling, and scams, uses Tether (USDT) on the TRON network, especially in Asia. Tether has worked with law enforcement to freeze accounts involved in this. Still, the fact remains: stablecoins are now a popular way to move illegal money because they’re fast, final, and easily accessible. For a country that treats preventing money laundering as a matter of national security, allowing this system in without any controls is a bad idea. So, they’re tightening the rules, restricting promotion, and keeping the issuance of digital currency public.

What Does This Mean for Education?

The education sector will feel this in practical ways. Chinese families can’t just use dollar stablecoins to pay for things like overseas tuition or online courses, even if the schools or platforms accept them. This makes it more important to use approved methods: bank transfers within the $50,000 limit, legal conversions with proof of need, or regulated payment services. Schools that recruit students from China should ensure their payment systems comply with Chinese regulations, not just global crypto trends. They should also be ready to support e-CNY payments where legal, and have robust systems for refunds and tracking bank-based payments.

Similarly, scholarships, research grants, and licensing deals will need to follow the rules. Hong Kong is important here. They’re starting to create their own stablecoin rules and might issue licenses soon. But because of Beijing’s intervention, the first companies to get these licenses won’t be big Chinese tech companies, and private renminbi-tied tokens will be slow to arrive. Universities with branches in Hong Kong can try out regulated Hong Kong dollar or U.S. dollar stablecoin programs for people outside mainland China while using e-CNY and regular banking for mainland transactions.

A Controlled Way Forward: e-CNY, mBridge

China isn’t saying no to digital money; they’re saying it needs to be run by the government. Transactions using the pilot e-CNY program have already reached trillions of yuan, with millions of people using digital wallets. Hong Kong has even started accepting e-CNY for payments at local stores. This is important for international education because it provides an official way to pay fees and stipends without relying on private stablecoins.

For bigger transactions, the mBridge project is becoming a reality, bringing China, Hong Kong, Thailand, the UAE, and Saudi Arabia onto a shared platform for instant international payments under central bank rules. This is the one to watch. If mBridge grows, it could enable scholarship funds from the Middle East to flow to Chinese universities – or licensing payments the other way – to move quickly and securely on central bank systems, instead of relying on traditional banks or private stablecoins.

The key takeaway here is that, because most stablecoins are denominated in U.S. dollars, any major country that controls inflows and outflows needs to view them as a form of imported monetary policy. The U.S. has made it easier for dollar stablecoins to exist, thereby strengthening the dollar system. China’s response is to ban stablecoins at home, pause private issuance next door, and push for government-controlled alternatives. As long as stablecoins are mostly U.S. dollar products, China won’t let them move freely through its system. The way forward is clear: design payments that respect China’s rules, support e-CNY where possible, and monitor mBridge.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Bank for International Settlements (2025). Annual Economic Report 2025 – III. The next-generation monetary and financial system. Retrieved December 16, 2025.

Bank for International Settlements (2025). Aldasoro, I. Stablecoin growth – policy challenges and approaches (BIS Bulletin No. 108).

Chainalysis (2024). The 2024 Geography of Cryptocurrency Report.

East Asia Forum (2025). Taylor, M. “Beijing blocks stablecoins to keep money under state control.”

HKMA (2025). “Regulatory Regime for Stablecoin Issuers (Cap. 656).”

HKMA / HKSAR Government (2025). “Stablecoins Ordinance to commence operation on August 1, 2025.”

IMF (2025). Cerutti, E. Understanding Stablecoins (DP/2025).

IMF (2025). “How stablecoins can improve payments and global finance.” IMF Blog, Dec 4, 2025.

People’s Bank of China / Reuters (2025). “China’s central bank vows crackdown on virtual currency, flags stablecoin concerns,” Nov 29, 2025.

Reuters (2024). “Hong Kong allows China’s digital yuan to be used in local shops,” May 17, 2024.

Reuters (2025). “Hong Kong passes stablecoin bill—one step closer to issuance,” May 21, 2025.

Standard Chartered (via Reuters) (2025). “Stablecoins could suck $1 trillion from EM banks,” Oct 7, 2025.

State Administration of Foreign Exchange (2017). “Annual quota of USD 50,000 for foreign exchange purchases by individuals.”

UNODC (2024). Casinos, Money Laundering, Underground Banking, and Transnational Organized Crime in East and Southeast Asia.

U.S. Congress / Reuters (2025). GENIUS Act (Guiding and Establishing National Innovation for U.S. Stablecoins), signed July 18, 2025.

Hong Kong Monetary Authority / BIS Innovation Hub (2024). “Project mBridge reaches MVP stage.”

Comment