Insider Trading by Politicians Is About Power, Not Secrets

Input

Modified

Leadership brings the trading edge; power beats tips Buys precede contracts, sales precede heat—disclosure failed Ban lawmakers’ individual stocks or require true blind trusts

Here's the thing that screams out at you: When politicians get promoted to party leadership, their stock trades start doing way better – like 40-50% better each year than similar folks. This happens after they get the promotion, not before. You see it most when their party runs the show, and companies get federal contracts or are grilled by Congress. This ain't just luck or guessing right on those earnings calls. This looks like they're tied to decisions that mess with prices. So, insider trading by politicians is about having the power to make decisions, not just knowing secrets. Recent studies show this clearly: either keep politicians out of investments, or deal with everyone losing trust in the markets and the government.

Politicians' insider trading: using decision-making for an advantage

The proof has piled up. Ten years ago, some studies suggested that members of Congress could beat the market. Regular members would've been better off with a basic index fund. But things change at the top. Normal members? No advantage. Real advantage? Power. When certain members become leaders – like Speaker, floor boss, whip, or caucus chair – their trades start raking in extra cash that lasts. It's a big difference: leaders' trades crush those of similar non-leaders by 40-50% each year. This data only includes people who traded both before and after their promotion. The timing is the key!. It's not that they are stock-picking geniuses; it's that leadership gives them new info and the power to set agendas.

Looking more closely at how this works makes the pattern clearer. Leaders do best when their party is in charge, which shows they control ideology. The boss's sales often happen before bad news hits certain companies. Also, their purchases occur around the same time the company receives more federal funding or a special contract. Laws also shift: if leaders buy a stock, their party is more likely to back laws that benefit that company and block measures that could hurt it. These are tangible outcomes, not just guesses. So, the long-term edge in insider trading by politicians comes from their ability to directly or indirectly influence factors that move prices.

Let's see how decision-making power turns into significant gains. Leaders decide what gets voted on and when. They help set the agenda for oversight and hearings. Running the floor and committees gives them early, detailed knowledge about which industries will get hammered and which will boom. That's why returns go up when the leader's party runs things. Leaders' sales look like ways to prevent losses, while their buys seem like bets on future funding. Contract data backs this up: companies that the leader buys stock in often get more contracts, including those special sole-source deals. It's hard to say this is just luck. It looks like they have extraordinary influence, or at least special access, that lines up with their investments.

Company access matters, too. Companies want to talk to the few lawmakers who control bills or influence regulators. Talking to these folks can turn into insider info, even if nobody is trying to trade favors. One study finds that trades through brokerages linked to politicians yield small but noticeable short-term gains (about 0.3% over five days). Other research focuses on negative trading – shorts, puts, and inverse funds. The profits here are clearer: from 2012 to 2023, negative-position members reported earning extra cash, peaking at around 1-2% after a couple of weeks. It's unbalanced: long buys are weak, while shorts and hedges are profitable. Markets seem to see when politicians report negative positions as important news.

Why the STOCK Act failed—and what actually is going to work

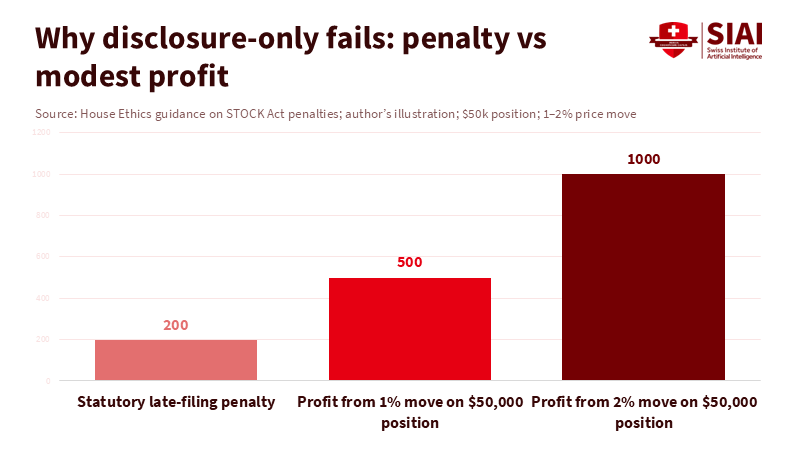

The STOCK Act of 2012 made things more open, but didn't change much. Members must report trades on time; the late-reporting fine is $200 and can be waived. That doesn't stop major trades. Watchdogs and reporters keep finding mistakes: many members miss deadlines, file fixes late, or report things far after they happen. Ethics people often think rules were broken, but the consequences are still light or unclear. So, a system that depends on people reporting stuff fails if those in charge can get and make information that impacts prices. Because voters and markets get it. In July 2025, a Senate group pushed forward a bill to ban trading by lawmakers (and maybe even top executives). In the House, a group wants members to sell stocks within months, with fines based on how much they trade and the recovery of profits from rule-breakers. Reports show many bills in Congress seeking to ban or limit stock trading by members. Good ideas are out there, like the Bipartisan Ban on Congressional Stock Ownership Act (H.R. 1679) and the ETHICS Act (S. 1171). The ideas may differ on whether to require blind trusts or allow mutual funds, but they all want one thing: no individual stocks for members and real penalties with oversight.

Another idea is to let them own stocks, but put up barriers. Independent people would have to approve trades. They would extend blackout periods around hearings, markups, and contract decisions, and force them to recuse themselves on things linked to their holdings. Fines would be based on how much they traded, and there would be a public record. But here's the deal: After the 2012 changes, leaders seemed to trade less, but their trades were still risky. The issue is not just about reporting fast. The problem is letting top decision-makers own – and actively trade – big investments in companies they can mess with.

What this means for school leaders, administrators, and investors

Schools aren't safe from this. They're tied to federal funding, state contracts, education software, student loans, and changing rules on data privacy and AI in schools. When party bosses control these areas, companies that sell software, tests, cloud services, or job training can benefit from new laws or hearings. Superintendents, provosts, and CFOs need to know this. Think about political risk when choosing vendors and renewing contracts. Line up your most significant contracts with committee areas and leadership investments that are made public. If these areas overlap, add cool-off periods to contract processes, require vendors to disclose political contacts, and force any campus leader with a special interest in a vendor to step back from the decision. The danger isn't just casual talk; it comes from the decision-making. Ors, think about congressional actions as policy suggestions. Don't use it for stock tips. Make tools that link leadership trades, legislative schedules, and federal contract money. If members are selling stock in a sector you invest in, assume there's growing risk and tighten things up. News lags, there could be problems, and leaders have advantages you can't recreate. Instead, use these signals to be safe, get cash ready, and talk to your companies about their policies on contacting politicians who trade. Also, boards need to keep track of how they handle risks when working with influential lawmakers. If members are shorting, that's a bad sign. Treat that as a real risk when checking your holdings.

Closing the loop

Here's the main thing: Markets move on decisions, and insider trading by politicians pays off most where power is highest. They have no advantage, while leaders – once they're in power – get rich. Small fines and reporting late won't fix trust. Trying to control information lags behind leaders who can make the information that impacts prices. The proper fix is basic: Either stop powerful members from trading stocks, or make enforcement treat conflicts like market risks, not just minor mistakes. The proof and public interest support stopping. There's also a good civic reason. A ban wouldn't fix everything, but it would make things clear. When leaders push a bill or grill a CEO, we shouldn't wonder who owns the stock. When contracts are transferred to a single company, we shouldn't check whether it's in a Speaker's portfolio. The studies show that leaders' sales often come before problems, and their purchases align with later contract wins. Also, their returns spike after they get to power. So, if we want markets and classrooms based on merit, ban stock trading by members, and make the ban include spouse and dependent accounts. The only things they can invest in are broad-based funds or something like a blind trust. That would turn decision-making power back into something suitable for everyone. Good for everyone.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Associated Press. “Left and right are joining forces to ban lawmakers from trading stock.” September 2025.

Business Insider. “78 members of Congress have violated a law designed to prevent insider trading and stop conflicts-of-interest.” January 3, 2023.

Campaign Legal Center. “Congressional Stock Trading and the STOCK Act.” September 5, 2025.

Colorado Leeds School of Business. “Profiting from connections: Do politicians receive stock tips from brokerage houses?” September 3, 2021.

Congress.gov. H.R.1679 — Bipartisan Ban on Congressional Stock Ownership Act of 2023 (118th Congress).

Congress.gov. S.1171 — Ending Trading and Holdings In Congressional Stocks (ETHICS) Act (118th Congress).

Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance. “Negative Trading in Congress.” July 29, 2024.

Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance. “Political Power, Personal Portfolios, and Risks for Corporate Governance.” December 10, 2025.

House Committee on Ethics. “Ethics in Government Act—Financial Disclosure Instructions (House).” 2023.

Politico. “Congressional stock trading ban gets Senate panel’s OK.” July 30, 2025.

VoxEU/CEPR. “Political power and profitable trades in the US Congress.” December 13, 2025.

Wall Street Journal. “Bipartisan Proposal Would Ban Stock Trading by Lawmakers.” September 2025.

Comment