Paying Good Teachers More – The Key to Better Education

Input

Modified

Raise base pay to close gaps and stabilize schools Use low-bias bonuses to retain high-impact teachers in hard posts Pair pay reform with clean screening and clear metrics to lift quality

We’re facing a serious problem: by 2030, we’ll be 44 million teachers short worldwide. We need to act fast to get more teachers and keep the good ones we have. Small changes won’t cut it; we need significant reforms. Here’s the idea: increase base pay for all teachers to provide stability and add fair bonuses to reward and retain teachers who help students learn. Set strict standards for teacher entry. Together, these steps—raising base pay, offering performance-based bonuses, and maintaining high entry standards—form the most transparent and most effective path to improving teaching quality. Doing only some might not fix the problem and could cause setbacks.

Good Salaries: The Foundation for Keeping Teachers

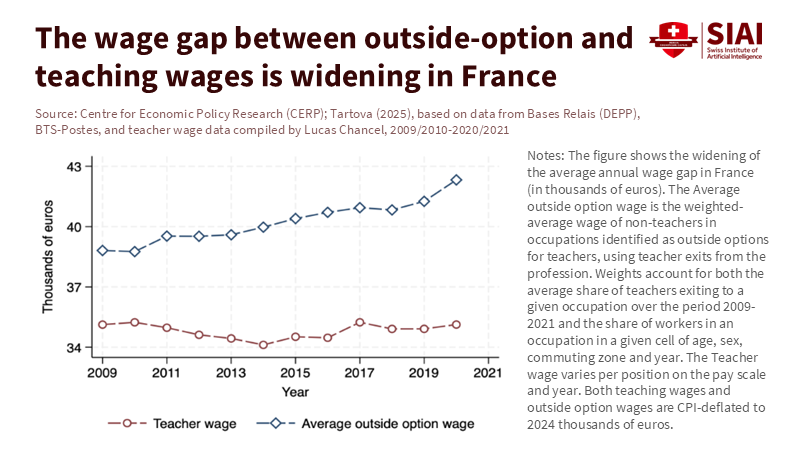

Getting salaries right from the start is super important. In the U.S., teachers are earning way less than other professionals with the same education, about 73 cents for every dollar. Benefits help a bit, but not enough. When teaching pays so poorly, good people leave. So, salary changes should start with consistent raises for everyone that match what people can earn in other fields, rather than just handing out random bonuses. Raises for everyone aren’t just about being fair; they’re about keeping good teachers. Studies show that even small pay increases can prevent teachers from leaving, especially in poorer areas, without affecting how well students learn. Even a tiny raise can make a big difference in keeping teachers in schools that need them most. This suggests that across-the-board raises are a solid way to start salary reform.

But simply raising base pay won’t completely solve the teacher shortage. Many schools still struggle to find certified teachers, especially in special education. Having empty positions hurts everyone, no matter how well the other teachers are paid. So, any salary changes need to consider supply and demand, paying teachers enough to keep and attract new ones, and encouraging teachers to work in areas where they’re needed most.

Rewarding Good Teaching Fairly

The idea behind performance pay is simple: reward teachers who are making a difference so they’ll stay. But figuring out how to measure performance can be tricky. Test scores can be a good way to see how a teacher is helping students grow, but they can change a lot from year to year. Observations can seem straightforward, but they can also be unfair because different people might rate teachers differently.

Past experiences tell us to be careful about how we measure performance. Smart salary changes will look at student growth over several years rather than just one, limit the weight any single measure carries, and avoid making big decisions based on a single quick observation. We’ve also learned a hard lesson. Significant changes to teacher evaluations in the U.S. promised to improve student performance, but often just caused stress. Turns out, many measures were unreliable or unfair, and that hurt trust, especially in disadvantaged communities. The wrong signals can backfire. That’s why bonuses should be focused and based on solid, fair measures – such as student progress over time, working in subjects with shortages, or helping other teachers.

The best way to handle this is to focus on two things: stabilizing the profession and rewarding good teaching. First, raise base pay for everyone to match the market. Then, add bonuses for working in shortage subjects or disadvantaged schools, for consistent, impactful teaching, or for mentoring other teachers. For example, England has had success with payments to retain math, physics, chemistry, and computing teachers early in their careers. This is a fair way to do performance pay.

Hiring the Right People

Even the best bonus system won’t work if the wrong people are filling the jobs. Raising base pay will attract more people, but we need to make sure we’re hiring the best. Systems that link merit-based hiring to what teachers know and how well they teach have seen improvements in new-hire performance. One significant reform raised salaries while also making it harder to get hired through a national exam. The result was better candidates and better teaching. It’s essential to set high standards before raising wages, or at the very least to align them closely with those standards.

Europe shows that starting pay and opportunities for career growth matter. Low pay drives people away from tough schools. Some systems have seen success by raising base pay and adding allowances, and they use fair and open hiring practices. For systems that are still developing, use pay to attract and maintain good standards through exams, interviews, and practice teaching. Poor hiring can lead to problems.

Global numbers make it clear we need to act. We not only need millions more teachers, but many countries also struggle with a shortage of candidates and weak management. Reports show shortages, uneven training, and unclear hiring processes that let weak candidates slip through. Pay is important, but not enough. We also need to invest in training, coaching, and career paths that reward good teaching without forcing teachers to become administrators to earn more. Bonuses should reward teachers who help students learn or assist other teachers, not just those with extra credentials.

Putting It All Together: A Teacher Salary Strategy

Here’s the framework: First, boost base salaries with raises that keep up with inflation to close pay gaps with other professions. Second, add bonuses for high-need subjects and schools to achieve long-term impact and support mentoring. And finally, have tough, merit-based hiring with clear standards and evaluations. Combining strong base pay, bonuses, and strict hiring is the only way to improve teaching quality by attracting, keeping, and assigning talent where it’s needed most.

Some might say that bonuses create division or that performance measures are flawed. But the evidence suggests that we should balance and integrate these measures rather than get rid of them. Looking at student growth over several years reduces the ups and downs. Classroom observations are more reliable when done by multiple people using clear standards. Mentoring and leadership go beyond test scores. Also, significant raises reduce the pressure on bonuses so that teachers won’t feel like a bad year can ruin their career. This isn’t about just tying pay to test scores; it’s about rewarding teachers for their sustained contributions and for serving in areas with the greatest needs.

You might also wonder if we can afford these changes. The reality is that we’re already paying for failures through high turnover, emergency credentials, and learning loss in poorer communities. Raises and bonuses are alternatives to these hidden costs. In tight budget situations, we should move money from general allowances to support that’s based on actual evidence of what works. Temporary retention payments can help with urgent shortages while we train more teachers. We can share annual reports on job openings, teacher turnover, and bonuses distributed to maintain public confidence.

Finally, some may point to places where uniform raises were a success and ask why we need to complicate things. But context matters. In systems with high standards and reliable evaluations, uniform raises help keep good teachers. In places with weak standards, blanket raises may attract the wrong people. The safest bet across different situations is a combination: a solid base pay to retain teachers, along with smart hiring and bonuses to guide efforts and stabilize hard-to-staff schools. This respects what works without the issues that have plagued earlier performance-pay programs.

The world needs 44 million more teachers, and students need access to good teachers now. Changing teacher salaries is the fastest way to get there. Set a higher base pay for everyone, reward those in subjects in short supply and underserved schools, and acknowledge sustained teaching performance. When these strategies are combined with good screening and clear rules, the profession becomes appealing, fair, and focused on what’s crucial. If we ignore these things, we’ll continue to pay the price of vacancies, turnover, and wasted potential. The choice is between simply adjusting numbers and setting a compensation deal that raises classroom learning. Start today.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Allegretto, S. (2024). Teacher pay rises in 2023—but not enough to shrink pay gap with other college graduates. Economic Policy Institute.

Bacher-Hicks, A., Kane, T. J., Staiger, D., & Winters, M. A. (2024). The role of wages in retaining effective teachers in the classroom. VoxEU/CEPR.

Department for Education (UK). (2025). Government evidence to the STRB. London: DfE.

Eurydice/European Commission. (2025). Teachers’ salaries in Europe 2023/2024 (Fact sheet).

National Center for Education Statistics. (2024). Most U.S. public elementary and secondary schools faced hiring challenges for the start of the 2024–25 academic year (Press release). Institute of Education Sciences.

RAND Corporation. (2023). Gitomer, D. H., et al. The sizzle and fizzle of teacher evaluation in the United States (Frontiers in Education).

The World Bank. (2024). Teachers (Topic page). Washington, DC: World Bank Group.

The Live Handbook. (2024). Teacher evaluation (overview of measures, reliability, and bias).

World Bank / IZA. (2024). Busso, M., et al. Evidence from a large-scale reform in Colombia (IZA DP No. 17294).

Comment