From Dialogue to Directive: How the Xiangshan Forum Became China’s Classroom for Global Governance

Input

Modified

Xiangshan Forum is China’s planning room for global governance Beijing fuses hard power and finance to shape rules Education must teach Xiangshan-era governance, standards, and AI/security

The Xiangshan Forum, held in Beijing in September 2025, gathered over 1,800 participants from 100+ countries. This is not the United Nations General Assembly. It's a military security conference that has now become a new center of world politics. The scale is telling. China uses the Xiangshan Forum to review its achievements and preview the future, reaching a growing coalition beyond the West, mainly in the Global South. The attendance number alone sends a strategic message: China now has the ability, narrative, and network to host a forum rivaling traditional security venues. While numbers don’t guarantee legitimacy, they create momentum. This year, the Xiangshan Forum made its size a statement, and that statement was a five-year plan for global governance.

Xiangshan Forum and the New Architecture of Global Governance

Beijing used the 2025 cycle to connect message, strength, and management. On 1 September, President Xi announced a Global Governance Initiative (GGI) at an SCO “SCO+” summit in Tianjin. He called for a “more just and equitable” order and placed the Global South at its center. The GGI aligns with the Global Development, Security, and Civilization initiatives, providing Beijing with a unified approach to systemic change. Two weeks later, at the Xiangshan Forum, Defense Minister Dong Jun delivered a 30-minute keynote—triple the length of his remarks in 2024—shifting from reassurance to rule-making language. This pairing is significant. Announce the initiative at SCO; promote it at Xiangshan; advance it through clubs and banks. That’s the plan. It reframes the Xiangshan Forum as a policy workshop rather than just a discussion space. It is where Beijing introduces governance rules for cyber, space, AI, and sea lanes while engaging states seeking alternatives to a U.S.-led order.

The choreography is precise. Analysts and officials describe the month in three acts: GGI at SCO, parade symbolism, then Xiangshan Forum messaging. The forum hosted more than 1,800 participants from over 100 countries, while Western governments reduced their representation. Dong’s speech condemned “hegemonic bullying” and asserted the PLA as a stabilizing force. The East Asia Forum warned that Xiangshan will matter only if diplomacy matches capabilities. Still, the event’s presence, speeches, and timing show intent: giving the forum strategic weight and making it a lasting complement—not a copy—to Singapore’s Shangri-La Dialogue. In short, the Xiangshan Forum is no longer reflecting others’ rules; it’s where China tests its own.

A final piece completes the picture: external validation with limits. Singapore’s defense minister used his Xiangshan Forum address to argue that major powers can “manage differences and tackle global challenges together.” This statement provided Beijing with a multilateral endorsement and reminded listeners about the limits of great-power rivalry. The EAF analysis took a harder line: the forum gains significance only if Beijing can match its capabilities with diplomacy across a diverse crowd. Considering both perspectives, the Xiangshan Forum now stands near Shangri-La as a site for rehearsing rules rather than just discussing them. It is a venue curated by China; it is also a space for middle powers to express their views and for education systems to learn to understand the new narrative.

From Muscle to Method: China’s Diplomatic Toolkit in the Global South

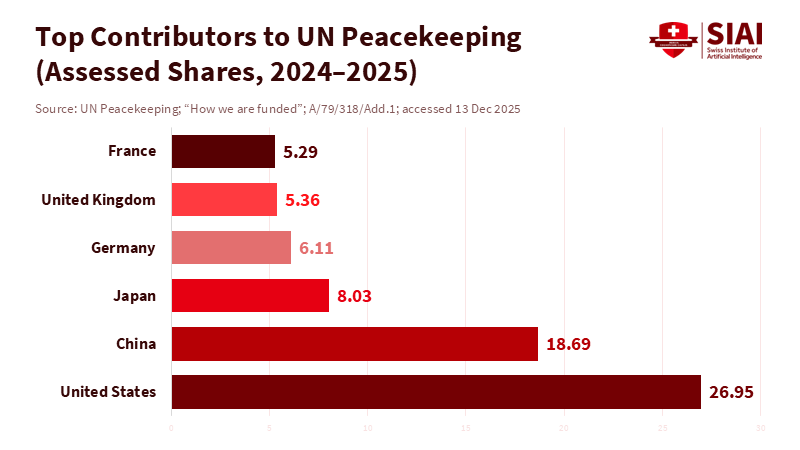

The Xiangshan Forum projects confidence because it is backed by real capacity. China’s official defense budget reached about 1.78 trillion yuan (roughly US$246 billion) in 2025, marking the seventh consecutive year with increases of around 7 percent. Budgets do not always translate into strategy, but they provide the resources for platforms, logistics, and training that give diplomacy—especially defense diplomacy—lasting power. China’s hard-power credibility makes the Xiangshan Forum more than talk. It serves as a platform for signaling supported by ships, missiles, aircraft, and military exercises visible from the Western Pacific to the Indian Ocean. This hard edge is complemented by institutional leverage within multilateral organizations, where Beijing is now the second-largest assessed contributor to UN peacekeeping, accounting for 18.69 percent of assessed contributions for the 2024–2025 period. While money can’t buy legitimacy, it does attract attention and influence in the halls where mandates and budgets are decided.

Arms and training complete the toolkit. SIPRI’s data from 2019 to 2023 show China as the largest supplier of major arms to Sub-Saharan Africa, with a 19 percent share, even as overall arms transfers declined from the previous five-year period. This doesn’t make Beijing the dominant exporter globally, but it does establish it as a key supplier and training partner in the very regions most represented at the Xiangshan Forum. Thus, the forum also acts as a user group meeting for clients, doctrine partners, and officials who share platforms and tactics. With club memberships, the network tightens. BRICS has expanded and introduced “partner country” tiers to broaden its reach; Indonesia’s entry as a full member in January 2025 boosted Southeast Asia’s voice in that club and added credibility to China’s narrative of a multipolar, Global South-led order. In this way, the Xiangshan Forum serves as the security-policy face of a broader club strategy.

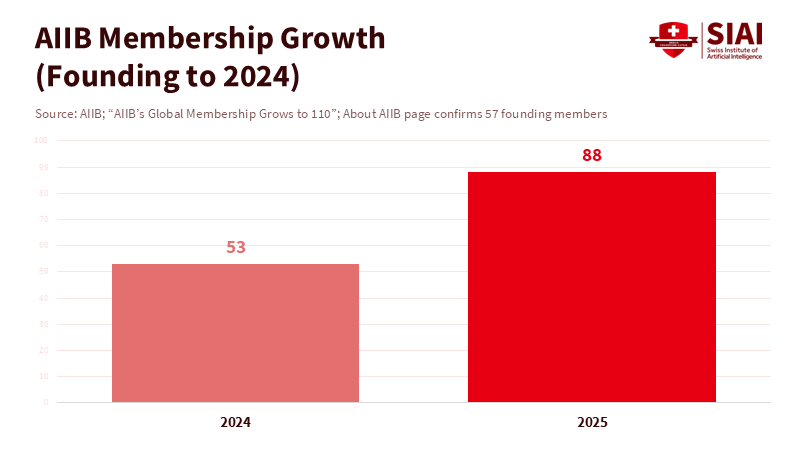

Finance strengthens China’s impact. The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank has 110 approved members, many from outside Asia, giving China a platform from the Balkans to the Pacific. Development finance is China’s most prominent channel. AidData reports over US$1.2 trillion in Chinese state-backed loans and grants to low- and middle-income countries between 2000 and 2023, plus hundreds of billions to high-income borrowers. Not every dollar brings leverage, and not every project succeeds. But the scale builds dependencies: procurement rules, standards, training, and political ties endure. Defense spending, peacekeeping, arms, training, clubs, and banks together form the diplomatic strength the EAF described. The Xiangshan Forum shows how that strength works.

Why Education Policy Must Adapt to Xiangshan-Era Diplomacy

An education journal should consider a simple question: what does the Xiangshan Forum mean for schools, universities, and ministries? First, curricula need to catch up with the governance landscape mapped by the forum. International relations and security studies programs should analyze the Xiangshan Forum alongside the Shangri-La Dialogue as essential cases. Courses on global governance should examine the new GGI and its links to earlier initiatives in development, security, and civilization. Students should review official speeches and independent assessments to compare claims to capacity. They should consider how Beijing uses concepts such as “sovereign equality,” “true multilateralism,” and “community with a shared future,” and trace their use in the SCO, BRICS, AIIB, the UN, and Xiangshan. This is not advocacy; it is necessary knowledge. Graduates will enter a world in which deals are negotiated across various settings. They should be trained to follow the connections back to the core policy.

Second, student mobility and research will shift as the Xiangshan Forum network expands. China may host about 550,000 international students by decade’s end, with Belt and Road links shaping attendance and studies. Confucius Institutes have closed or rebranded in parts of the West but still operate—about 496 institutes and 757 classrooms worldwide by 2023, according to independent researchers—while new bilateral language centers fill gaps. Universities should see this not as a struggle for classrooms, but as proof that language, law, standards, and security are converging. This trend will shape careers in public administration, logistics, energy, and technology. Education ministries in Africa, the Middle East, South Asia, and Southeast Asia should expect scholarship paths, dual-degree security and infrastructure programs, and targeted procurement training.

Third, educators should view the Xiangshan Forum as a forecasting tool for skills. When Dong and other speakers highlight “rules for emerging domains,” they refer to the most essential competencies: understanding standards, basic open-source intelligence, maritime domain awareness, and AI risk governance. Teacher-training colleges and public-policy schools should develop capstone projects that simulate Xiangshan-style negotiations over shipping lanes, satellite cooperation, or data access. Technical universities should integrate engineering labs with modules on export controls, sanctions, and due diligence so graduates understand the legal landscape. Business schools should explain how AIIB procurement differs from World Bank rules. Across all disciplines, programs need a risk-tiered partnership framework: approve low-risk exchanges, strictly regulate dual-use research, and produce transparent funding audits. The goal is not to withdraw; it is to engage knowledgeably. This is how education policy can keep pace with the world, as outlined by the Xiangshan Forum.

Risks, Rebuttals, and the Road Ahead

There are significant objections. Critics claim the Xiangshan Forum is merely a spectacle: large numbers with little substance. Some argue that Chinese loans create debt issues, that arms sales provoke conflict, and that grand initiatives are just slogans. Others highlight the sharp decline in Western participation in 2025 and caution that a forum dominated by the Global South could become an echo chamber. Certain aspects of this critique hold. Many Belt and Road projects have stalled or been renegotiated in the past five years. Analysts also note that the GGI requires more substance to avoid becoming hollow. Nonetheless, scale is a reality. The attendance of over 1,800 participants is not fabricated; it reflects the demand for alternative venues and tangible offers related to training, finance, and standards. On the ground, many governments are seeking more opportunities for negotiation. The Xiangshan Forum offers them one—on terms set by China that others must learn to navigate.

A better policy response is to combine openness with clear boundaries. For universities, this means forming risk-tiered partnerships, establishing transparent governance for dual-use research, and maintaining public records of foreign funding. For ministries, it involves instilling Xiangshan Forum literacy throughout the civil service: understanding how initiatives transition from speech to budget; comparing AIIB procurement against World Bank standards; negotiating status-of-forces language or maritime-security cooperation while safeguarding national legislation. It also calls for more experiential learning in the Global South: capstone projects at African Union and ASEAN institutions; joint clinics on infrastructure procurement; comparative studies on AI safety that examine Chinese proposals alongside OECD and G7 work. None of this requires choosing sides. Instead, it is about preparing students and officials to interpret a multipolar narrative and act confidently within it.

We should conclude where we started: with the Xiangshan Forum’s attendance and its significance. More than 1,800 delegates filled venues in Beijing because China now provides a forum, a financial structure, and a narrative that many governments outside the West find useful. Dismissing this as a fleeting occurrence misses the point. The Xiangshan Forum has evolved into a planning session for a new governance syllabus, revised annually and offered to an expanding network of partners. The appropriate response is to teach that syllabus, test it, and, when necessary, counter it with evidence and law. Education policy must engage with this reality. If we want students and institutions to thrive in a world where standards are a strategic tool, then courses, partnerships, and research ethics must align with the Xiangshan Forum context. Start with the statistic that opened this essay. Then create the classroom necessary to address it.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

AidData. (2025, November 18). China’s Global Loans and Grants Dataset, Version 1.0.

Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. (2024, September 26). AIIB’s Global Membership Grows to 110.

East Asia Forum. (2025, December 11). Xiangshan Forum shows the muscle behind China’s diplomacy.

QS. (2025, October 28). Global student flows: China.

Reuters. (2025, January 6). Indonesia joins BRICS bloc as full member, Brazil says.

Reuters. (2025, March 5). China maintains defence spending increase at 7.2%.

SCMP. (2025, September 18). Takeaways from Chinese Defence Minister Dong Jun’s speech at the Xiangshan Forum.

SCMP. (2025, September 16). As the US retreats, can Xi Jinping’s new initiative shape the future world order?

SIPRI. (2024, March 11). Trends in International Arms Transfers, 2023 (Fact Sheet).

Singapore MINDEF. (2025, September 18). Speech by Minister for Defence at the 12th Xiangshan Forum.

The Diplomat. (2025, September 23). 2025 Xiangshan Forum: China Enters a New Era of Assertive Global Governance.

UN Peacekeeping. (2025). How we are funded (assessed contributions 2024–2025).

Comment