From Freeze to Flow: Governing Euroclear’s Windfall on Immobilised Russian Assets

Input

Modified

EU freezes ~€210bn; windfall profits flow, not principal Route proceeds via EU/G7 loans to steady, education-first support Preserve trust: strict legality, transparency, shared risk

A single number now shapes the conversation: around €210 billion of Russian state reserves are frozen in Europe, most of which are held at Euroclear in Brussels. In December 2025, EU governments decided to freeze these assets indefinitely. This ended the six-month renewal routine and removed a major procedural veto risk. This change is significant. It opens the way to use the ongoing cash proceeds—the interest Euroclear earns when blocked coupons and redemptions are reinvested into safe instruments—and provides long-term financial support for Ukraine. Legally, the principal is untouched; the profits flow. The policy question is more complex: how do we convert unpredictable windfalls into reliable funding for rebuilding schools, paying teachers, and ensuring students can learn during war and displacement—without breaking the law or the trust that holds financial systems together?

What “Euroclear immobilised Russian assets” really are

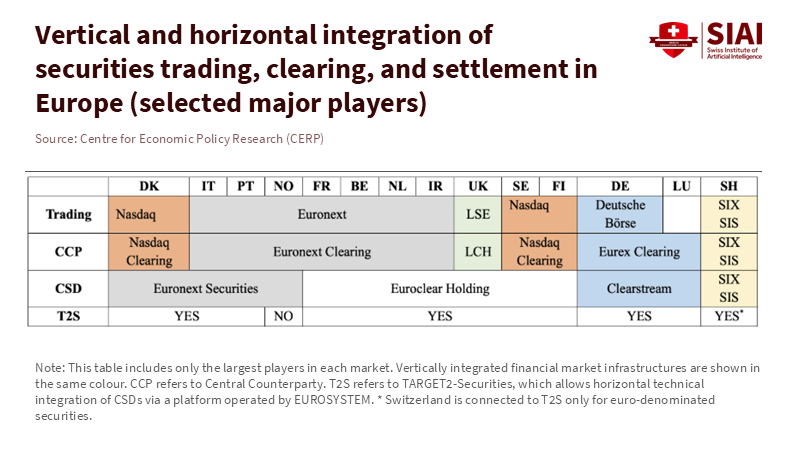

When sanctions began in 2022, payments to sanctioned beneficiaries on Russian-linked securities were not permitted. Those coupons and redemptions started to accumulate in cash on Euroclear’s balance sheet. Under regulations, Euroclear must reinvest such balances in safe, liquid assets. As interest rates rose, the earnings grew significantly. Euroclear reported approximately €3 billion in interest on Russia-sanctioned balances for the first nine months of 2023 and €4.4 billion for the full year 2023, resulting in €1.085 billion in Belgian corporate tax that year. By April 2024, Euroclear reported a balance sheet of €199 billion, with €159 billion tied up in sanctioned Russian assets—showing how substantial the blocked flows had become. These assets are not fixed deposits belonging to Euroclear; they are custodial proceeds that are legally frozen, held in trust until the legal status changes.

In 2024, the interest stream continued to rise. Independent estimates indicate Euroclear’s interest income on the frozen portfolio surpassed €6 billion that year, with “close to €5 billion” sent to support Ukraine through new EU and G7 mechanisms. However, this surge was not guaranteed to continue. By the first three quarters of 2025, flows reportedly dropped by about 25%, indicating that rate cycles and portfolio composition can change annual earnings by billions. The lesson is clear: windfalls are inconsistent. To address this, if policymakers want stable education budgets during wartime—covering salaries, psychosocial support, replacement textbooks, and safe shelters—they must buffer volatility with multi-year instruments backed by those proceeds, rather than depending on yearly interest.

Lawful leverage, not confiscation: the new framework

The EU did not immediately move to seizure. In May 2024, the Council adopted a legal package to redirect net windfall profits—not the principal—created by central securities depositories from these immobilised balances. The new rules require a 99.7% financial contribution of net proceeds to the EU budget, after accounting for risk and tax deductions. Of this, 90% is allocated to the European Peace Facility and 10% to reconstruction via the EU budget. Central securities depositories can retain a small portion to meet capital and risk requirements. This is narrow by design. It keeps the principal safe, uses only extraordinary revenues generated by sanctions and rising rates, and creates a lawful path for transferring funds.

The framework has since expanded. In January 2025, the European Commission disbursed €3 billion as part of a G7 loan, which will be repaid using these proceeds. In December 2025, EU leaders decided to indefinitely freeze the €210 billion, linked to a larger plan for a €90–165 billion loan to Ukraine in 2026–2027, backed by revenue from the immobilised portfolio. This model provides bridge financing. It turns irregular annual cash flows into predictable multi-year disbursements now, with repayment linked to future proceeds or to Russia’s eventual reparations. It combines careful legal work and practical budget planning.

Risk, reciprocity, and the custodian’s dilemma

Caution continues. Belgium, Euroclear’s host, has warned of potential litigation and liability risks if the revenue-backed loans are poorly designed. Euroclear itself has noted legal and operational risks as the EU advances the asset-backed model. Russia’s central bank is suing Euroclear in multiple venues. Legal experts note that, while contracts governing custody have expired or are blocked by sanctions, new claims might challenge the line between lawful revenue use and unlawful confiscation. These risks affect risk premiums, custodian behavior, and the cost of Ukraine’s future debt.

Despite these risks, the legal and policy landscape has solidified. The EU’s windfall policy does not affect sovereign principal and is grounded in sanctions law, regulatory standards for central securities depositories, and a public purpose: Ukraine’s defense and reconstruction. The G7 loan structure adds predictability without necessitating outright confiscation. Meanwhile, the scale of immobilised state assets remains large—around €260–300 billion across the G7 and its partners—of which about €210 billion is in the EU, primarily at Euroclear. The law remains in flux; a final court ruling may take years. But the combined framework is defensible and adaptable enough to change if courts set new limits.

Turning a windfall into a pipeline for education

Education should be a priority use of these proceeds because wars not only destroy infrastructure, but they also undermine human capital. A child out of school for a year can lose skills that take years to regain. The Euroclear-immobilised Russian assets now support a funding stream that can be directed to teacher pay, school heating, remote learning, and psychosocial support. The rationale is straightforward: keep spending focused on human capital and system continuity, where each euro spent on stability prevents much greater long-term losses. Policymakers should establish dedicated amounts within the larger Ukraine fund, with clear metrics for teacher retention and student attendance. Education spending during conflict needs the most predictability; the asset-backed loan transforms unpredictable interest into stable multi-year funding.

Two elements make the pipeline effective. First, the 99.7% rule ensures a high capture rate of net proceeds, minimizing losses. Second, the move to an indefinite freeze supports the more extended periods needed to create reliable school-year budgets. But volatility is absolute: reported proceeds fell about a quarter in 2025 compared to 2024’s peak. The solution is not to cut classroom spending; it is to manage cash flow using the loan framework, with annual education amounts committed upfront and adjusted based on actual revenues. If future rates decrease further, the EU and G7 can adjust by extending loan periods or adding guarantees. That approach keeps teachers and students in place while navigating legal challenges and the ongoing conflict.

Accountability without paralysis

Critics argue this approach could politicize financial systems, provoke retaliation, or discourage the use of European services for reserves. These risks must be considered. The current setup targets extraordinary revenues from sanctions, not regular earnings; it affects no principal; and ends with the conflict and legal resolutions. Euroclear and similar bodies can still fulfill their primary role: safe, neutral settlement. To reassure reserve holders, the EU should issue quarterly reports on proceeds, allocations, and balances, have independent boards audit the process, and keep the purpose limited to human capital and essential services. Legitimacy comes from focus and transparent reporting.

There is also a concern that Belgium or Euroclear could face the consequences if lawsuits go poorly. Here, the policy solution is collective. Liability should be shared across the EU (and, ideally, the G7) when measures support a common foreign and security policy. This is already seen in the loan design and in Germany’s announced guarantees. Combine this with a regulatory exception that allows central securities depositories to retain capital reserves and manage risk in a controlled manner. With these safeguards, the system can function effectively without compromising its credibility.

The way forward

Looking ahead, the figures will continue to change. Interest rates may decline. Legal challenges will persist. But the course is clear. The EU has accepted indefinite immobilisation; it has chosen to harness windfall profits lawfully; and it is developing tools to turn inconsistent flows into dependable support. In light of this, education should be at the forefront of these efforts. It keeps families together during displacement. It maintains the skills needed to rebuild communities and economies when the fighting ends. And it offers hope to children whose lives have been narrowed by disruption and fear.

The €210 billion figure is not a trophy. It is a tool. Used wisely, it can stabilize an entire education system through the toughest years of conflict. The call to action is simple: establish a multi-year, education-first fund within the loan; publish straightforward quarterly reports; and keep the legal framework clear—no principal, only net windfall proceeds, dedicated to a well-defined public purpose. If we achieve this, the term “Euroclear immobilised Russian assets” will not symbolize inaction. It will represent that law, finance, and basic decency can still work together in the current reality.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Bruegel. (2024, June 24). How to harvest the windfall profits from Russian assets in Europe.

Council of the European Union. (2024, May 21). Extraordinary revenues generated by immobilised Russian assets: Council greenlights the use of windfall net profits to support Ukraine’s self-defence and reconstruction.

Council of the European Union / EEAS. (2024, May 21). CSDs’ contributions and retention for risk management (explainer).

Council on Foreign Relations. (2025, November 21). How to use Russia’s frozen assets.

European Commission. (2025, January 10). Commission disburses first €3 billion to Ukraine of its part of the G7 loan, to be repaid with proceeds from immobilised Russian assets.

European Parliament Research Service. (2025). Confiscation of immobilised Russian sovereign assets.

Euroclear. (2023, Oct. 26). Q3 2023 trading update.

Euroclear. (2024, Feb. 1). Euroclear delivers strong performance in 2023.

Euroclear. (2024, Apr. 30). Strong first quarter results: sanctioned assets on balance sheet.

Euroclear. (2025, Feb. 5). Euroclear delivers strong results in 2024.

FRANCE 24. (2025, Dec. 9). Euroclear details ‘concerns’ over EU frozen-asset plan.

Lexology. (2024, May 24). Regulation 2024/1496: 99.7% contribution on CSD windfall profits.

Reuters. (2023, Oct. 11). Belgium expects €2.4bn in tax on frozen Russian assets to fund Ukraine.

Reuters. (2025, Dec. 12). EU agrees to indefinitely freeze €210bn in Russian assets, removing obstacle to Ukraine loan.

The Guardian. (2025, Dec. 12). EU to freeze €210bn in Russian assets indefinitely.

Verfassungsblog. (2025, Apr. 4). Frozen Russian state assets: legal pathways and limits.

VoxEU/CEPR. (2025). Euroclear and the geopolitics of immobilised Russian assets.

Comment