The Omnibus Isn’t Neutral: Why Europe’s Shortcut to “Simplification” Could Lock In Big Tech—and How Others Should Respond

Input

Modified

Omnibus simplification risks deepening Big Tech lock-in Bind it to portability, open APIs, and switching If others copy, copy the guardrails—not consolidation

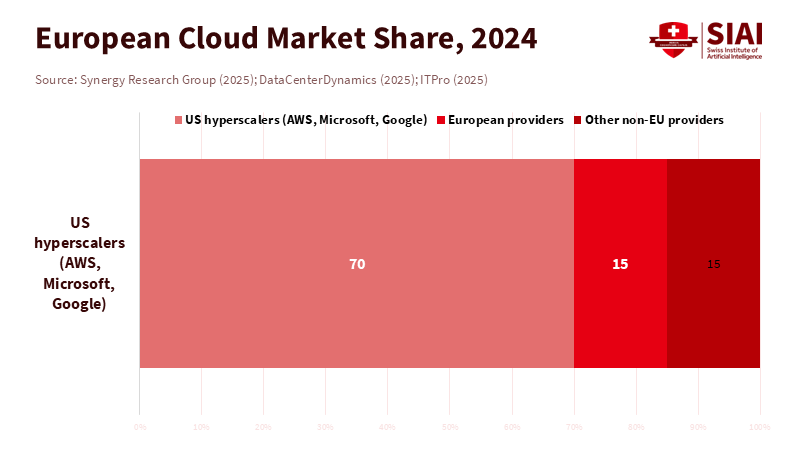

Europe spent roughly €61 billion on cloud services in 2024. Local providers captured only about 15% of that market, a share that has remained steady even as spending increased. The rest largely went to three U.S. tech giants. This outcome is not by chance. It highlights deep structural power in data, infrastructure, and switching costs. Now consider the new EU Digital Omnibus Regulation package, which is presented as a way to cut red tape and save billions in compliance costs. If simplification targets markets that already favor established companies, it can deepen the divide rather than level the playing field. This is the main policy risk, especially for education systems and young edtech firms that rely on fair access to data, interoperable standards, and open procurement. Countries from London to Canberra will be looking at the EU. If they follow the EU's surface-level promise without its essential support structures, they will likely face the same results: quicker dominance and less innovation.

EU Digital Omnibus Regulation: what it does and why it matters

The EU Digital Omnibus Regulation comprises two proposals adopted by the Commission on November 19, 2025. One focuses on implementing the AI Act, while the other streamlines parts of the broader digital rulebook. Supporters argue that the package reduces redundant filings, aligns timelines, and creates predictable obligations for smaller firms. Critics caution that simplifying regulations across markets could undermine hard-earned protections under the GDPR, the Data Act, and e-Privacy rules. The most significant aspect is timing. The Commission suggested postponing stricter "high-risk" AI compliance until late 2027, framing it as a reasonable, business-friendly bridge. In concentrated markets, such delays are not neutral. They favor larger firms with resources, legal teams, and computing power. These firms are the most prepared to deliver products.

Despite tripling revenues since 2017, European cloud providers’ market share fell from 29% to 15% as global firms grew. EU cloud spending will likely rise in 2025, but market share lags. Meanwhile, only 55.6% of Europeans have basic digital skills—short of the 2030 goal of 80% and below the target for ICT specialists. As education systems buy more digital services, smaller domestic suppliers and skill pipelines fall behind. The Omnibus may reduce bureaucracy, but could entrench incumbent power without reforms to switching, procurement, and enforcement of the Digital Markets Act.

A wave of analysis from European policy institutes has converged on this point. They argue that the omnibus approach may weaken safeguards while failing to open markets meaningfully. Europe needs more than just consolidation to make digital services competitive. Some experts warn that a deregulatory trend, disguised as “innovation,” will shift bargaining power from public institutions to dominant platforms. Others link simplification to strategic risks in cloud and AI supply chains if not paired with pro-competitive measures. The message is clear: simplify, but ensure guardrails are in place and that tools promote entry and interoperability.

Copycat risks and opportunities beyond Europe

The EU Digital Omnibus Regulation will not just be considered in Brussels. Legislators in the U.K., Canada, Australia, Japan, and Singapore are grappling with the same balancing act: reduce friction so firms can deliver products faster, while preventing an advantage for established companies. The EU often sets the agenda. When it standardizes how AI, data, and privacy rules interpret overlapping obligations, other countries typically follow suit to ease cross-border challenges. This presents both an opportunity and a risk. If the EU’s model emphasizes timeline relief and filing relief without a strong pro-competitive design, others will replicate the same imbalance in their markets, particularly in areas where procurement is centralized and public services are purchased at scale.

Consider education technology and research computing. Public universities from Toronto to Sydney are increasingly adopting managed platforms that integrate identity management, learning analytics, storage, and proctoring. In markets dominated by larger firms, slight compliance relief tends to favor companies with all-in-one solutions. Smaller local vendors still face high integration costs and barriers to accessing data. The result is a form of dependency that seems efficient in the first year but becomes costly in the fifth year, when switching costs become significant. Policymakers who mimic the EU Digital Omnibus Regulation without complementary measures—such as portability mandates, interoperability in contracts, and assistance with cloud switching—will find that “simplification” accelerates consolidation in public-sector digital services.

There is also a fiscal angle to consider. Many countries rely on public procurement to support local edtech innovation. Venture funding is often cyclical; when it drops, stable contracts become crucial. Europe’s edtech funding fell from about $1.2 billion in 2023 to roughly $839 million in 2024, even as the number of deals held steady. This signals challenges for young firms that need steady revenue to survive funding downturns. If omnibus-style reforms reduce compliance costs but do not create procurement opportunities for smaller suppliers with guaranteed data access, the policy will lessen paperwork but deprive the industry of necessary resources. The lesson is straightforward: tie simplification to competition, or it will amount to deregulation under a different name.

What it means for education systems and edtech

For ministries and university leaders, the EU Digital Omnibus Regulation highlights a systemic issue. Schools are becoming more digital each year, yet the skill base is thin and inconsistent. Only 55.6% of the EU population has basic digital skills, while the 2030 goal is 80%. Every EU household should have gigabit internet, and all populated areas should be covered by 5G by 2030, but progress remains uneven. In practice, larger vendors compensate for local capacity deficiencies with bundled services, credits, and integration efforts. This addresses immediate needs but shifts power dynamics over time. Educators and administrators should view every procurement as an opportunity to foster a more competitive market, not just a quicker way to deploy tools. This means prioritizing open data formats, enforcing data portability in contracts, and demanding modular designs that allow smaller vendors to integrate without reverse-engineering proprietary systems.

The funding landscape emphasizes this need. After a surge during the pandemic, European edtech investment cooled, then showed a cautious rebound in the first half of 2024 before declining again in the second half. The slowdown does not indicate a lack of demand for improved digital learning or assessment. Instead, it reflects tighter capital availability, a more challenging path to scaling, and buyer reluctance. Policymakers often respond by easing compliance to “simplify” things for suppliers. This may help slightly. However, the real issue is market access, not just paperwork. If procurement becomes centralized with single-vendor platforms using proprietary data systems, smaller edtech companies cannot compete or even test their products. A more effective strategy is to link omnibus simplification to a “competitive demand” toolkit: modular contracts with limited lot sizes, data portability rules that remain intact regardless of vendor changes, reference architectures for identity, consent, and learning records, and funds to help universities transition to new providers without disrupting academic activities.

A smarter playbook for regulators

What would a pro-competitive, education-focused version of the EU Digital Omnibus Regulation look like? How should other countries adapt it? Start by addressing the timing issue. If high-risk AI rules are postponed to December 2027, use this time to require strong, verifiable risk management in public-sector deployments now. Make algorithm transparency and human oversight prerequisites for public education contracts, rather than optional add-ons. Link simplification to better enforcement of existing responsibilities under the Digital Markets Act, paying explicit attention to cloud switching and fair licensing in research and education. The goal is not to slow down rollouts; instead, it is to create an environment where many firms can compete based on quality and trust, not just size.

Next, turn procurement into a tool for shaping the market. Provide guidance stating that any platform acquired by a public education entity must (a) export all user data in open, documented formats every month; (b) allow third-party modules via published APIs with fair, reasonable, and non-discriminatory terms; and (c) pass a staged switching assessment, in which a small unit can switch in 60–90 days without help from the vendor. Fund this switching assessment through a pooled facility accessible to universities, financed by national digital budgets or innovation funds. Though it may seem procedural, it is key to facilitating market entry. This approach also mitigates the competitive advantage that might otherwise arise from omnibus simplification.

Lastly, address the skills and infrastructure gap that benefits established companies. The 2030 goals—80% basic skills, every household on gigabit internet—are not soft targets; they are essential market conditions. Every euro spent on digital skills and AI training decreases reliance on bundled "all-inclusive" offers that hinder long-term flexibility. Every improvement in campus connectivity reduces the dependence on proprietary systems. And since the digital skills gap in Europe is behind target, the focus should be on prioritizing teacher training and data stewardship—so public purchasers can confidently demand portability and modularity.

Finally, acknowledge the concentration issue. Europe’s cloud market remains controlled mainly by a few non-European companies. This dominance is long-lasting because it is rooted in data gravity and developer communities, not just pricing. Simplification alone will not change this. Other countries considering an omnibus approach should combine it with portability requirements and, when relevant, structural solutions against tying arrangements or anti-competitive licensing. They should also pursue targeted industrial policies that work—such as shared platforms for privacy-conscious learning analytics, national research clouds with open interfaces, and collaborative investments in reference datasets that any qualified provider can access under equal terms. These actions are not protectionist but rather competitive strategies that render simplification safer.

Returning to the initial fact: In 2024, Europe spent €61 billion on cloud services, with local providers capturing only 15%. If policymakers implement the EU Digital Omnibus Regulation as merely "cleaning up the rulebook" without establishing switching rights, open procurement, and skills development, that 15% will serve as a ceiling rather than a foundation. Education will be among the first to feel the consequences. Universities will struggle to change tools, negotiate contracts, or adopt privacy-conscious AI independently. Young firms with valuable ideas will be hindered by proprietary data systems. There is an alternative route. Simplify regulations, but ensure simplification is tied to competition. Use public procurement to demand data portability. Invest in skills so that schools and universities prioritize quality over the false security of all-in-one solutions. If Europe takes this approach, other regions will follow its example rather than merely imitating the label. Copy the EU Digital Omnibus Regulation only if you also include the necessary safeguards. Otherwise, you will duplicate the concentration.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Brighteye Ventures. (2024). The European Edtech Funding Report 2024. (Deal trends and totals). Retrieved January 2024.

Bruegel. (2025). The European Union needs more than the digital omnibus to make digital services competitive. (Policy analysis).

CEPR VoxEU. (2025). Simplification without disempowerment: Rethinking the Digital Omnibus Regulation. (Column).

European Commission. (2024). Report on the State of the Digital Decade 2024. (Skills and connectivity targets).

European Commission. (2025). Digital Omnibus package press materials. (Proposal overview).

ECFR. (2025). Thrown under the omnibus: How the EU’s digital deregulation fuels US coercion. (Commentary).

EdWeek Market Brief. (2025). European ed-tech venture capital investment fell to $839 million in 2024. (Market analysis).

Reuters. (2025). EU to delay ‘high-risk’ AI rules until 2027 after Big Tech pushback, as part of the Digital Omnibus. (News report).

Synergy Research Group. (2025). European cloud providers’ market share steady at ~15% as market hits €61 billion in 2024. (Industry data).

Comment