Counting People, Counting Capacity: A Practical Rule for Europe's Optimal Immigration Level

Input

Modified

Ageing Europe needs an optimal immigration level Set ~0.6–1.0% yearly, adjusted by jobs, housing, and language Link flows to capacity and invest to keep growth and trust

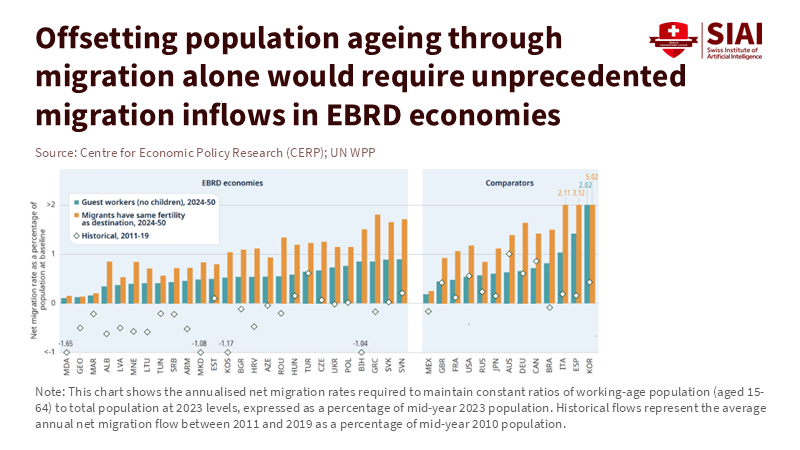

Across the EU, the old-age dependency ratio has risen to around 37%. This means there are fewer than three working-age adults for every person over 65. By mid-century, this ratio is expected to reach the mid-50s, further reducing the support base. Now consider another stark fact. To maintain the working-age share, several aging economies would need net migration at a scale Europe has never seen. Italy and Spain would require annual inflows exceeding 2% of their populations. Slovenia would need about 1.7%, which is almost nine times its average intake from the 2010s. These figures are not alarm bells; they are hard math. Europe needs a policy that views immigration as a crucial factor with clear capacity limits. The goal is to set an optimal immigration level that keeps the economy strong and the social contract intact. The number should be ambitious enough to make a difference and manageable enough to allow for proper integration.

Ageing arithmetic and the limits of substitution

Demographics are not just a trend; they are a reality. Europe is aging quickly, and this trend is here to stay. The percentage of older adults in the EU will continue to rise for decades. By 2050, the EU's old-age dependency ratio is expected to increase to the mid-50s. Fewer workers will mean more retirees. This alone will slow growth and limit funding for schools, training, and research. Immigration can help. However, the scale needed to stop the working-age share from declining is much larger than what political discussions suggest. Recent studies indicate that, even under "guest worker" assumptions, many economies would require annual migrant inflows of 0.5% to 0.9% of their populations. Suppose migrants settle and have children at local rates. In that case, the necessary inflows exceed 1% in nearly half of the affected economies and exceed 2% in rapidly aging countries. Migration can help, but it cannot fully replace births.

The supply side also poses challenges. Aging is now a global issue. The pool of potential migrants is shrinking in many regions. One recent estimate suggests that aging economies will need about 655 million more working-age adults by 2050 to maintain current working-age ratios. Potential contributions from younger areas will not be enough. Europe is not alone in its search; it competes with the United States, Canada, and East Asia for the same individuals. That competition drives wages up and tightens the selection process. In this context, Europe must set realistic targets and ensure strong integration so every newcomer can contribute effectively. The alternative is clear: accept faster aging, slower growth, and increasing pension and health costs. The numbers allow for little compromise.

Defining the optimal immigration level

The false choice between open and closed borders has wasted time. A better framework involves a practical approach. The optimal immigration level is the net migration a country can handle each year while maintaining labor market performance, classroom quality, housing affordability, and social trust. It should be defined as a range rather than a fixed point. The lower limit reflects guaranteed integration capacity, while the upper limit reflects the ability to handle sudden increases in labor demand. Europe has relevant benchmarks. In 2023, the EU issued over 3.7 million first residence permits to non-EU citizens, the highest number ever. In 2024, that figure dropped to about 3.5 million. These numbers show what systems can handle under pressure. They are not a plan for steady conditions. The corridor must align with lasting capacity, not short-term spikes.

A workable corridor for advanced European systems is about 0.6% to 1.0% of the population per year, adjusted for labor-market tightness and local capacity. This is based on earlier studies and recent data: in 2024, about three-quarters of migrants across the OECD were active in the economy, and around 71% were employed, with unemployment rates below 10%. When job matching is efficient and language support is adequate, countries can approach the top of the corridor without overwhelming schools and housing. If classroom and housing capacity lag behind, the safe rate is closer to the lower end—around 0.3% to 0.5%—until those issues are addressed. This is not a moral claim; it is a practical one. Set the optimal immigration level based on what institutions can deliver at a high quality, then invest to raise that capacity year by year.

Paying for assimilation: who contributes and when

The fiscal issue is crucial. The evidence is more nuanced than slogans suggest. Across the OECD, the net budget impact of migrants usually hovers around small fractions of GDP. It depends on employment rates, wages, and access to benefits. When migrants are young and employed, the fiscal balance tends to be neutral or positive. When they face barriers to work or experience slow recognition of their credentials, the budgetary balance worsens. The UK provides a recent concrete example. Skilled workers on work visas contributed about £16,300 in their first year—higher than the £14,400 contributed by the average working Briton, and far above the £800 from the average adult. This is not a universal trend, but it demonstrates what good design can achieve. If you select for work, reduce barriers to employment, and clear pathways, the net fiscal balance turns positive sooner.

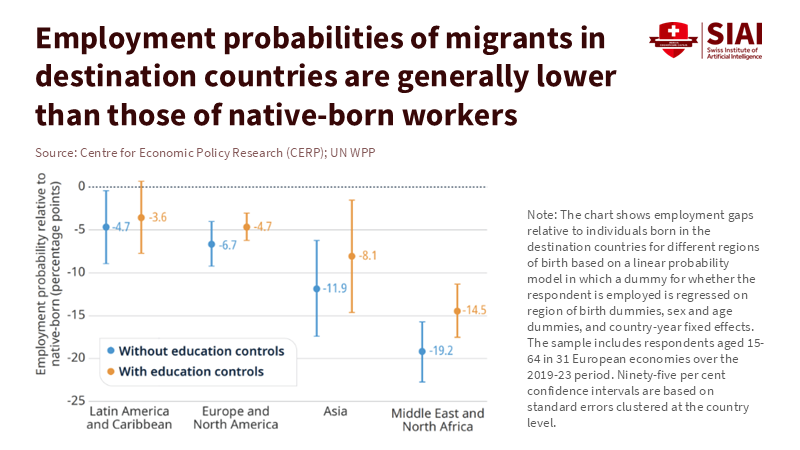

The speed of integration affects both cost and contribution. In European Labor Force Survey data, foreign-born adults have, on average, a 10-percentage-point lower employment rate than natives with similar profiles. After adjusting for education, this gap narrows to about 7.4 points. That is a space relevant to policy. Faster recognition of skills, intensive language training linked to real job openings, and early work rights for humanitarian entrants can close this gap. When employment increases, the fiscal balance improves too. The broader economic benefit is also evident. The 2022 surge in immigration is expected to add 0.2% to 0.7% to potential output in recipient EU countries by 2030, even after factoring in initial congestion in schools and services. The message is clear: the optimal immigration level works best when integration keeps pace with entry.

From politics to practice: a rules-based regime for the next decade

Europe needs a rules-based system that enshrines the immigration corridor in law and encourages capacity enhancements. Start with three indicators. Indicator one is labor-market tightness, measured by job vacancies and employment rates for recent arrivals. When vacancies rise above a certain level, and newcomers' employment exceeds a target, the upper limit of the optimal immigration level can increase. Indicator two is integration capacity: language-class seats and credential assessments completed per 1,000 newcomers; school class sizes; access times for primary care. When these indicators are favorable, flows can approach the top of the corridor. Indicator three is housing supply: new builds per 1,000 residents and rental price inflation. When housing is limited, the corridor naturally narrows. This shifts the discussion from slogans to actual service delivery. It connects border numbers to those in schools, clinics, and construction sites.

A straightforward example illustrates how this rule works. Consider a country with 10 million people. A corridor of 0.6% to 1.0% means 60,000 to 100,000 net migrants annually. If language-training seats cover only 70% of last year's intake and housing construction falls below expected levels, the rule would set the following year's cap at around 0.5%—or 50,000—unless the government invests in new language programs and speeds up permit approvals for building. If, midway through the year, vacancies remain high and language seat coverage reaches 100%, the cap can increase within the corridor. This maintains flexibility and keeps political attention on visible capacity improvements. It also respects local situations. Cities that meet the capacity requirements can accept more migrants; those that do not will not. The result is a managed system that grows with competence rather than headlines.

Objections deserve clear answers. One concern is that large inflows burden welfare systems. They can, especially when newcomers wait months to work or when schools are short-staffed. The solution is not to focus solely on reducing numbers. It is to expedite access to work, connect language training to employment, and provide early fiscal support to communities that host large numbers of new arrivals. Another concern is cultural cohesion and safety. Evidence of crime varies across countries and time. However, it is consistent with the literature that early employment, local support, and school success lower risk. Border security and identity checks matter, but so does a clear path into civic life. The optimal immigration level does not ignore these issues. It addresses them by connecting flows to the systems that help strangers become neighbors.

A final concern is making unrealistic promises. Migration cannot "solve" aging alone. Even Europe's record high intake of first residence permits in 2023 falls short of what is needed to maintain the working-age share in many countries. Global supply constraints loom as other wealthy regions recruit, too. Therefore, Europe needs to broaden its focus. Increase employment for older workers by improving workplace health and flexible hours. Boost female labor force participation through reliable childcare. Keep students on track for middle-skill and high-skill jobs where shortages persist. Immigration is one tool among several. It buys time and talent. It does not eliminate demographic challenges. A rules-based corridor that acknowledges both realities is the best place to start.

The case for an optimal immigration level is not ideological; it rests on calculations and institutional capacity. Europe is already facing a 37% old-age dependency ratio and is projected to reach the mid-50s by mid-century. Several economies would need annual inflows of 1% or more—sometimes 2%—of their populations to maintain the current working-age share. This is unlikely and may not be practical if schools and housing cannot keep up. A capacity-based corridor addresses the right issue. It accepts that migration is essential to slow aging and ties the number of newcomers to the real ability to integrate them effectively. It also compels governments to invest in what makes immigration successful: faster access to jobs, quicker credential checks, larger language programs, and more housing. Set the corridor. Publish the metrics. Adjust transparently. Europe can still shape its future labor force. The only poor choice is to drift into deeper aging without a plan to manage both the numbers and the capacity needed for sustainability.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Bruegel. (2024). Beyond retirement: a closer look at the very old.

CEPR VoxEU. (2024). Macroeconomic implications of the recent surge in immigration to the EU.

CEPR VoxEU. (2025). The scale and limits of migration in offsetting population ageing.

Eurostat. (2024). More than 3.7 million first residence permits in 2023.

Eurostat. (2025). 3.5 million first residence permits in 2024.

Eurostat. (2025). Old-age dependency growing across EU regions.

Migration Observatory (University of Oxford). (2024). The fiscal impact of immigration in the UK.

OECD. (2024). International Migration Outlook 2024.

OECD. (2025). International Migration Outlook 2025.

United Nations. (2024). World Population Prospects 2024: Summary of results.

Financial Times. (2024). Skilled migrants contribute more to public finances than working Britons, report finds.

Comment