The Capacity We Keep Missing in Ageing Economies

Input

Modified

Closing gender and 60+ gaps offsets ageing Frontiers need more hours; laggards need jobs and childcare Use 5-year targets, neutral taxes, late-career training

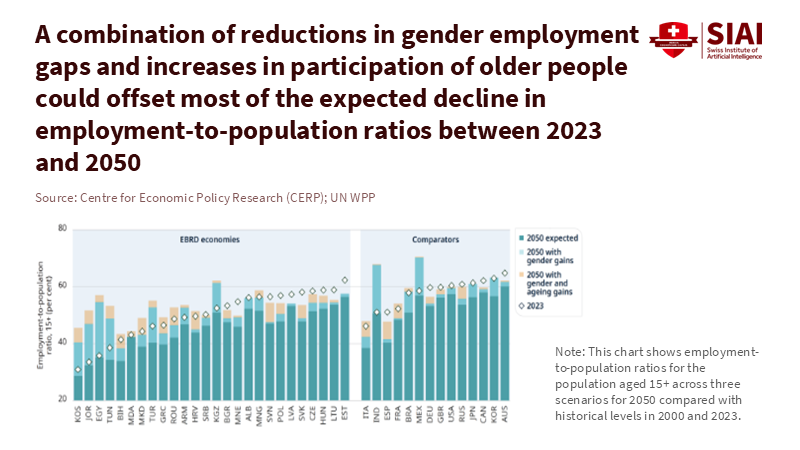

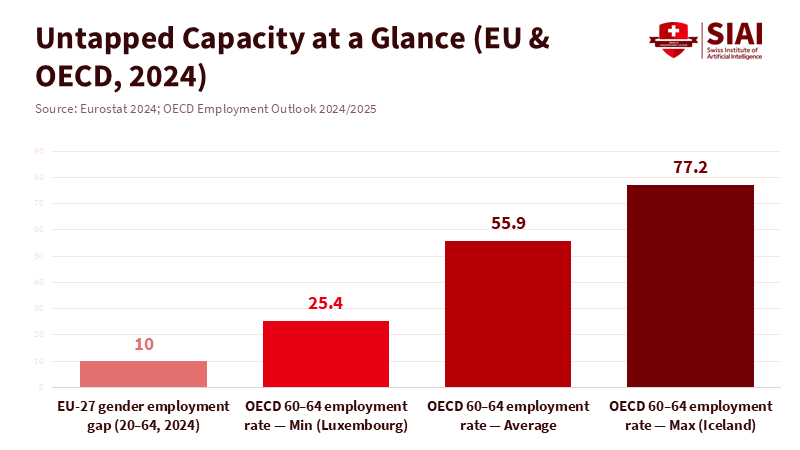

In 2024, the European Union still had a gender employment gap of 10 percentage points. About 80.8% of men aged 20 to 64 were employed, compared to 70.8% of women. Across the OECD, employment among people aged 60 to 64 averaged 55.9%, ranging from 77.2% in Iceland to 25.4% in Luxembourg. These two facts highlight a key truth: the fastest way to counterbalance demographic decline is to increase employment among women and older workers. Lagging countries have a significant opportunity for growth; those that already perform well see smaller gains. New research from CEPR shows that closing gender gaps and increasing employment for those over 60 could offset most of the expected decline in employment-to-population ratios caused by ageing. This isn't a distant issue. It's a set of immediate choices about childcare, taxes, training for older adults, and pension policies that can either turn untapped potential into jobs or let it go to waste as the population ages.

Women and Older Workers Employment: The Overlooked Growth Lever

The policy debate often focuses on long-term fertility, AI productivity, or limits on migration. Yet the real opportunity is right in front of us. In 2024, the EU recorded a high employment rate of 75.8% among people aged 20 to 64. Still, this figure masks significant differences by sex and age. Women's employment remains ten points lower than men's, and activity among those in their early 60s varies widely by country. This variability is essential. Countries close to the performance frontier will gain little from broad targets; countries farther back can achieve substantial results. OECD evidence shows that employment among older workers has risen over time. However, there is still plenty of room for improvement for those aged 60 and above. This is where policy can have quick benefits: small increases in participation lead directly to higher output and tax revenues without waiting decades for demographic changes.

What scale is at stake? The latest analysis from CEPR shows that reducing the gender gap while increasing employment among those aged 60 to 64 and 65 and older can counteract much of the expected decline in employment ratios in many ageing economies. The idea is straightforward. Where social norms, institutions, and incentives hold women and older adults back, employment rates lag behind robust comparators. Raising those rates to match the top performers can yield immediate, measurable benefits. The OECD warns that without such changes, ageing alone will slow income growth through 2060. Increasing participation among women and older individuals is the first and often only cushion with immediate impact. For this reason, women's and older workers' employment should be central to macroeconomic strategy, not on the sidelines.

Europe's Split Screen: Same Ageing, Different Barriers

Europe presents a divided picture. On one side are high-employment countries that still waste hours and skills. The Netherlands and Germany exemplify this. Female employment is high, yet many women work part-time. In 2023, over half of employed women worked part-time in the Netherlands and Austria; in Germany, nearly one in two did. German mothers are particularly likely to work fewer hours compared to fathers. Journalists and economists attribute this to gaps in childcare and to tax policies such as joint taxation and "mini-jobs" that discourage second earners. When many women intentionally limit their hours, the economy misses out on skilled workers, and the pension system faces future funding shortfalls. Europe cannot afford a scenario in which high participation masks persistent underuse of work hours. The solution is straightforward: better childcare options, fairer tax treatment for second earners, and more part-time leadership roles—all proven strategies.

On the other side are countries with low overall employment where both women and older adults face barriers. Italy's situation is stark. In 2024, only 67.1% of those aged 20 to 64 were employed, the lowest in the EU; Greece and Romania were also below 70%. These gaps are structural, not temporary. They reflect inadequate childcare options in some regions, ongoing informality, regional disparities, and, in some areas, conservative attitudes toward women working full-time. They also show that leaving the workforce in the early 60s is a challenge. Moving these countries even halfway toward the EU average could transform their growth trajectories and public finances. Eurostat's 2024 data indicate that the EU average is solid. The issue lies in distribution. Closing the employment gaps for women and older workers is the most straightforward way to raise the lowest levels—and to do so with policies that national governments can control.

Japan's Underused Engine and What It Teaches

Japan illustrates two things: policy can engage sidelined workers, and work hours still matter. In 2024, Japan's labor force reached a record 67.8 million, thanks to more seniors and women entering the workforce. However, total work hours did not rise. This situation—more workers, flat hours—suggests that just increasing employment won't boost growth unless jobs come with the right hours, skills, and productivity. Japan's female labor force participation rate hit about 52% in 2024, according to World Bank data. This marks progress, but it still lags behind many European countries, indicating further potential, especially if social norms, care facilities, and pathways to returning to work continue to improve. Since the mid-1990s, Japan's working-age population has declined by about 16%. The case for bringing more women and older adults into the workforce is mathematical, not ideological.

For other aging economies, Japan's lessons are practical. First, allowing flexible work hours for late-career employees keeps valuable workers engaged. Second, creating a pathway for women to return after raising children must be intentional, not a rarity. Third, reducing hours without raising productivity won't close the gap. The key takeaway is clear: connect women's and older workers' employment to sectoral demands, not just overall numbers. Expand mid-career training linked to skill shortages, develop transition programs that help part-time workers move to full-time roles within a year, and fund short courses that upgrade digital and management skills for those over 55. OECD employment reports highlight the potential to increase employment rates for the 60 to 64 age group, easily surpassing many current national averages if pension ages, partial-retirement options, and workplace designs change together. The right combination, not just the slogans, is what creates meaningful change.

From Levers to Timetables: What to Do Now

The first step is to focus on the areas with the most significant potential for growth in each country. In high-employment Northern Europe, the key issue is increasing hours, not just jobs. Tax systems need to stop penalizing second earners; childcare must adequately cover the needs of full-time work; and promotions should recognize part-time leadership as standard, not atypical. Germany's ongoing discussions about tax splitting and "mini-jobs" serve as an example: aligning incentives with full-time opportunities for women could quickly improve both hours and productivity. In lower-employment Southern and some Eastern European countries, the top priority is simply getting more people into their first jobs. This means providing more subsidized childcare slots in areas with low availability, activating support for women returning to work after long breaks, and making ergonomic changes to maintain the involvement of people in their early 60s. Across the EU, these initiatives should complement, not oppose, technological advancements and immigration. They represent a near-term growth strategy that doesn't rely on what happens in Brussels, Washington, or markets next.

Timetables are just as important as action lists. Set a five-year timeline with annual goals for women's and older workers' employment, categorized by age, region, and sector. Designate a responsible party for each goal. Offer quarterly updates tracking childcare availability, return-to-work statistics after parental leave, uptake of part-time leadership roles, average hours for mothers with school-age children, and employment rates among 60 to 64-year-olds. Link financial support to progress. The economic rationale is solid. The OECD estimates that without intervention, ageing alone will lower income growth through 2060. Increasing participation among women and older adults is one of the few strategies that can soften the impact right now. The EU's record employment rate shows the system can change; the question is whether we will act on the critical areas. The evidence, from Eurostat to CEPR, suggests the same answer: target gaps that can be closed within a single political term.

The initial numbers set the benchmark. A 10-point gender employment gap in the EU. A 50-plus-point difference in employment rates for those aged 60 to 64 across wealthy countries. We should not wait for a fertility rebound. We don't need to rely on breakthroughs in AI. We need to boost employment for women and older workers in places where policies, social norms, and incentives still hold them back. In nations near the performance frontier, hours are the key issue. For those far from it, securing the first job is the step that can ignite growth, financial flexibility, and equitable pensions. The approach will differ by location, but the underlying idea is the same: leverage the capacity already available. If we address the evident gaps, we can mitigate much of the demographic drag that feels unavoidable today. The costs of inaction are tangible. They include slower growth, weaker public services, and reduced retirements. The solutions are also clear. They involve timelines, budgets, and regulations that prioritize this needed shift.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

CEPR (2025). “Raising employment among women and older workers: A policy lever for ageing economies.” VoxEU, 4 December 2025.

Eurostat (2025a). “EU’s employment rate reached almost 76% in 2024.” Eurostat News, 15 April 2025.

Eurostat (2025b). “Employment gaps for women & people with disabilities.” Eurostat News, 27 May 2025.

Le Monde (2024). “Why women’s working hours in Germany are still hindering the country’s growth,” 2 September 2024.

Nippon.com (2025). “Seniors and Women Boost Japan’s Labor Force to Record High,” 18 February 2025.

OECD (2024a). “Labour Market Situation—Updated April 2024.” Statistical Release, 17 April 2024.

OECD (2024b). OECD Employment Outlook 2024. OECD Publishing, July 2024.

OECD (2025a). OECD Employment Outlook 2025. Chapter “Navigating the golden years: Making the labour market work for older workers,” 9 July 2025.

OECD (2025b). “Without Remedy, Countries With Aging Populations Are Set for Weaker Income Growth.” Media coverage of OECD findings, 9 July 2025. Wall Street Journal.

World Bank (2025). “Labor force participation rate, female (% of female population ages 15+)—Japan, 2024.” DataBank.

Comment