When Voters Lead, Law Follows: Public Opinion and Climate Policy After the IRA

Input

Modified

Support is broad, underestimated Local clean jobs drive votes Show local data; build pipelines

The most crucial fact in climate politics today is not about a molecule or a megawatt. It’s a number: 89%. That’s the share of people across 125 countries who believe their government should do more regarding climate issues. Two-thirds, or 69%, say they would donate 1% of their income each month to make it happen. However, most citizens feel they are in the minority. They think only 43% of others would contribute. This gap between reality and perception hides a crucial force. Public opinion and climate policy are now closely connected, but misunderstandings of social norms blur this connection. In the United States, this unclear connection still influences votes, investments, and classroom discussions. It also explains why information about costs and jobs often does not resonate. Closing the perception gap and showing that support is widespread, intense, and local will determine how quickly climate law aligns with public demand.

Public Opinion and Climate Policy: The Hidden Majority

American views on climate are clear; they are consistent and enjoy majority support on many policies. For instance, in late 2024, 83% of Americans supported tax credits for home energy efficiency, and 79% backed tax credits for companies developing carbon capture technologies. Furthermore, 69% said large businesses are doing too little about climate change, and 8 in 10 felt frustrated by political gridlock. These are not marginal numbers; instead, they represent the center of the electorate. Importantly, they coexist with strong support for clean energy basics: the Yale Climate Opinion Maps report 77% support for funding renewable energy research. Taken together, this provides a solid foundation for effective climate law and is broad enough to cross party lines on specific measures, even when elite opinions differ. The problem, however, is not a lack of public interest. It is a lack of connection between stable preferences and legislative results.

Yet connection improves when the public can see itself. Global evidence shows strong support for climate action, but a widespread misunderstanding of that support. People back climate policies, but they underestimate others’ willingness to contribute by an average of 26 percentage points. This collective underestimation forms the key perception gap: people assume there is far less support than actually exists. This misperception is significant because cooperation often depends on the belief that others will act. The solution is not vague messaging; it is visible majorities that are relevant to local contexts. Where voters learn the proper level of support, their willingness to act increases. When they see benefits nearby, skepticism fades. This is why credible, district-level opinion data and specific, localized results should be part of the policy process, not just included in press releases after votes. Show the majority to the majority, and make it relevant to their county and main street.

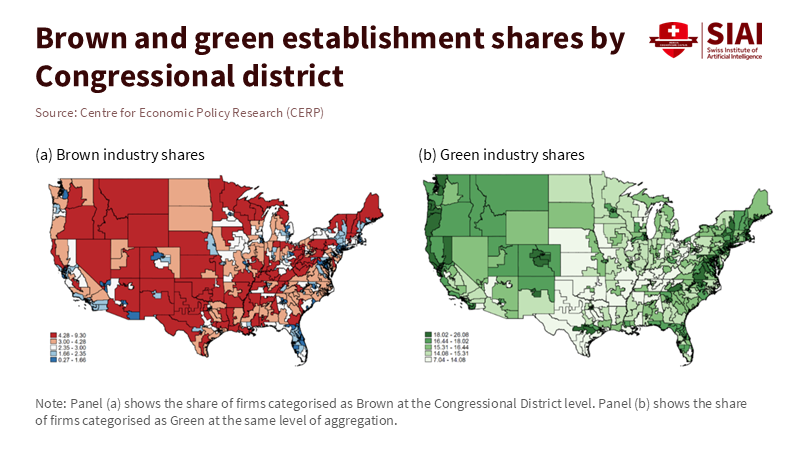

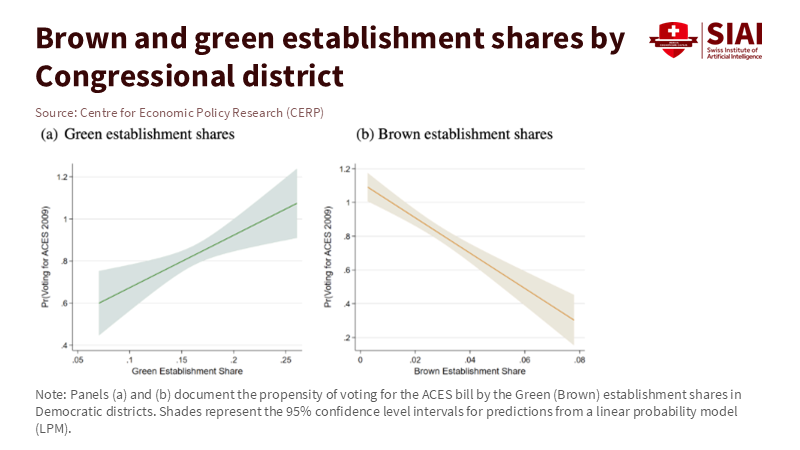

According to research by Johannes Matzat and Aiko Schmeißer, workplace unions can influence the political attitudes of both workers and management, potentially shaping how local economies and job sectors influence climate policy votes. When they vastly outnumbered the brown ones. According to a report from OpenSecrets, in the 2024 Congressional elections, candidates who raised the most money from outside their states or districts tended to perform strongly: 82 percent of House candidates and 58% of Senate candidates in the top 50 for non-local donations won their races. Representatives respond to their district’s major employers, especially in competitive seats. Public opinion influences votes, but local job dynamics often weigh heavily.

According to Energy Innovation, the Inflation Reduction Act has significantly impacted local job markets by helping to create over 400,000 new jobs and spurring $600 billion in private investment in clean energy since its enactment.S. clean energy and transportation investment hit $75 billion, 5.3% of private investment, with over half from household EVs, heat pumps, and distributed systems. According to the Clean Investment Monitor, utility-scale clean energy and industrial decarbonization projects attracted $23 billion in investment during the second quarter of 2025, with $22 billion allocated to clean electricity and $1 billion to industrial decarbonization. The report notes that as factories and supply chains expand, local employment and wages increase. This shift slowly redefines who is considered “our” employer and reshapes the incentives for regional representatives. Jobs gradually adjust the boundaries of ideology.

Bridging the Perception Gap in Public Opinion and Climate Policy

Policymakers often misjudge public sentiment due to the same perception gap. In 2025, researchers surveyed delegates at the UN Environment Assembly. On average, they estimated that only 37% of people would contribute 1% of their income to climate action, far below the actual global figure of 69%. This underestimation is a clear example of the perception gap at the leadership level and breeds caution, slowing lawmaking. It also skews media narratives, which focus on conflict while overlooking consensus. Closing this gap is a policy tool, not just a nice addition to communication efforts. It is cheaper than subsidies, faster than lawsuits, and more genuine than tribal signals. If leaders recognized that a vast public wants action—and is willing to contribute a little for it—they would be more inclined to push for necessary reforms: upgrading the grid, speeding up permits, and cleaning up industries. The mandate exists; the reflection remains unclear.

That clarity begins with district-level opinions, not national averages. For example, Yale’s maps reveal a supermajority of support for funding clean-energy research across most of the country. To build on this, combine those local opinion facts with local benefit details. Track, by county, the jobs, tax revenue, and energy savings from new projects, and create a simple “Opinion-to-Outcome” table that any resident can understand. Furthermore, require agencies to attach this to major decisions, as we do with environmental impact statements. In schools and colleges, develop civics modules that challenge students to estimate their community’s climate views, compare these with actual data, and write a short memo to their city council. Each time a community realizes it is less divided than it thought, the political cost of action decreases—and the possibility of law increases. That is how public opinion and climate policy can support each other.

From Opinion to Outcome: Institutional Design That Works

Salience matters. So does fairness. Americans strongly support policies they can see and use, such as home-efficiency credits, support for new technologies, and upgrades that reduce bills. Meanwhile, cost myths persist. However, the pricing reality is straightforward. In 2024, 91% of new utility-scale renewable projects generated power at a lower cost than the least expensive new fossil alternative. Specifically, onshore wind averaged $0.034/kWh and solar PV $0.043/kWh. Worldwide, renewables saved $467 billion in fossil fuel costs. These are not trivial savings. In fact, they translate to savings for households, school districts, and small businesses. When citizens recognize that the cheapest kilowatt is clean, and when they connect a local project to lower bills or better-paying jobs, support shifts from being a preference to part of their identity. That is when public opinion evolves from mere survey responses into a driving force.

To realize this evolution, design institutions need to ensure the transition. First, increase the visibility of shared support: publish quarterly state and county “opinion briefs” alongside project dashboards, and have agency leaders testify about them. Next, highlight fairness in the distribution of benefits: maintain popular targeted credits and visible community reinvestment in the areas where projects are developed, because voters favor policies that treat them as partners. Third, incorporate local jobs into policy planning: involve training providers and school districts early, and require that new facilities demonstrate a clear link from local classrooms to local employment. Importantly, none of this requires changing mindsets. It requires closing the perception gap, making the benefits clear, and aligning incentives where laws are crafted: in districts where employment-based changes occur one plant at a time. That is how public opinion and climate policy can stop missing each other and start moving in syn.c.

The public has already moved. According to a report from Stanford University, Resources for the Future, and ReconMR, most Americans still support increased government action on climate change. However, support for some specific policies has declined since 2020. The remaining challenges—misunderstood norms, outdated views of local industries, and the false belief that campaign money can override job-based incentives—are solvable. Illuminate the true majority. Record district-level opinions and benefits before votes. Continue to establish clean factories where brown jobs once anchored the economy. Then measure and share the results in classrooms that prepare future voters and officials. The key fact remains: the majority is not quiet—it is unheard. When policymakers recognize it, the law will follow the voters, as it should. This is the challenge facing educators, administrators, and legislators now: make the hidden majority visible and allow it to lead.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Andre, P., Boneva, T., Chopra, F., & Falk, A. (2024). Globally representative evidence on the actual and perceived support for climate action. Nature Climate Change, 14, 253–259.

Clean Investment Monitor. (2025, November 20). Q3 2025 update. Rhodium Group & MIT CEEPR.

Fang, X., Ettinger, J., & Innocenti, S. (2025). United Nations Environment Assembly attendees underestimate public willingness to contribute to climate action. Communications Earth & Environment, 6(622).

International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA). (2025, July 22). Renewable Power Generation Costs in 2024 (summary and press materials).

Pew Research Center. (2024, December 9). How Americans view climate change and policies to address the issue.

Frey, C. B., & Llanos-Paredes, P. (2025, December 4). The political economy of climate policy: Evidence from the American Clean Energy and Security Act. VoxEU (CEPR).

Yale Program on Climate Change Communication. (2025). Estimated support for renewable energy funding.

Comment