Who Wins When Rare Earth Export Restrictions Bite?

Input

Modified

Export restrictions shift rare earth profits and risks inside producing countries Indonesia and China gain leverage but concentrate benefits in big firms Stronger labour and environmental rules are needed so local communities share the gains

In 2025, a top Chinese rare-earth producer informed investors that its net profit for the first three quarters had increased by about 280 percent compared with the previous year. Prices for key rare-earth products had risen. New rare-earth export restrictions were tightening the supply. Meanwhile, governments and commentators warned that these controls could limit the availability of materials for electric cars, wind turbines, and defense equipment. We usually hear stories about geopolitics and trade wars. However, in the mining regions supplying this system, a quieter story is developing. Rare-earth export restrictions are not only a tool of foreign policy. They also serve as a domestic lever, shifting income, risk, and bargaining power among miners, large firms, local communities, and the state. Suppose the discussion focuses solely on global value chains. In that case, we miss a fundamental question: who really wins and who loses at home?

Reframing Rare Earth Export Restrictions

Most public discussions view rare earth export restrictions as weapons aimed externally. China’s licensing rules, technology bans, and controls on products containing its minerals are seen as responses to Western trade and technology restrictions. Indonesia’s 2014 ban on nickel ore exports is celebrated as a bold effort to move up the value chain. Export restrictions do influence global power, but they also reshape the domestic mining economy. They determine who sets prices, who reaps large profits when international prices rise, and who faces job losses and environmental impacts when demand drops or regulations tighten. In practice, rare earth export restrictions resemble industrial policy directed inward rather than simple trade policy.

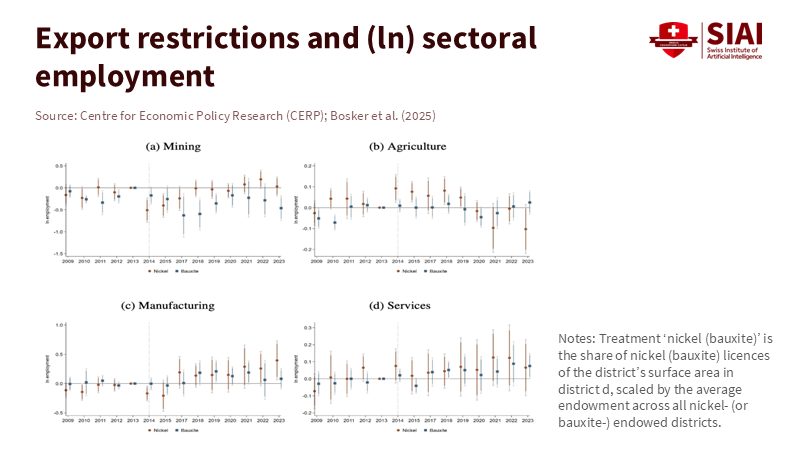

Evidence from Indonesia’s nickel situation makes this clear. Recent research on the 2014 export ban shows that employment in nickel-rich districts eventually rose by about 3 percent. This translates to about 3,400 additional jobs per average nickel district, totaling nearly 58,000 across all nickel districts. Initially, mining jobs decreased but recovered once smelters opened, and local processing grew. In contrast, bauxite districts with minimal new investment lost about 1.5 percent of jobs, or around 23,000 positions overall, with most losses in mining. The same export restriction thus created clear winners and losers within one country. It shifted bargaining power from small miners to larger downstream companies that could wait out the shock.

Indonesia’s Nickel Ban as a Cautionary Tale

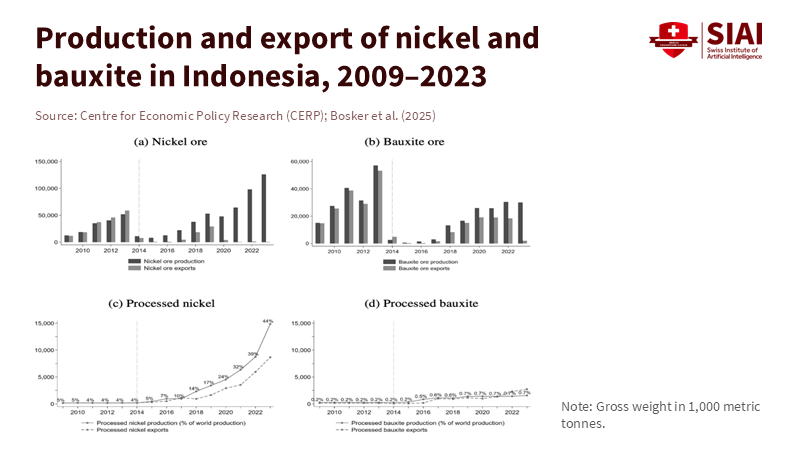

Indonesia now exemplifies how export controls can increase domestic value. In 2023, it mined about 1.8 million tons of nickel, close to half of global output. By that year, it had attracted roughly $30 billion in investment for smelters and industrial parks processing nickel at home. Processed nickel products contribute nearly 10 percent of exports, making Indonesia a leading stainless-steel exporter. One detailed study reports that value added in the iron and steel industry rose by about 5.6 percent between 2011 and 2020, increasing the value-added share of total exports by roughly 1.1 percent. Nationally, these figures look impressive. On paper, the export ban seems like a clear win.

However, life on the ground is more complex. Fieldwork and local statistics suggest that the export ban lowered domestic ore prices and empowered a small group of smelter operators. A major industrial park in Central Sulawesi employs around 38,000 workers, including several thousand from China. Yet, poverty in the surrounding district has only decreased from about 15 to 12 percent since the mid-2010s. This decline is only slightly faster than the national average. Reports from nickel regions reveal dangerous working conditions, weak unions, and communities trading cleaner land and water for uncertain wage benefits. Much of the profit goes to foreign investors and domestic business elites. At the same time, residents bear the bulk of the social and environmental costs.

The political lesson is clear. Export bans can increase domestic value and change a country’s position in global supply chains. They do not guarantee widespread local development. They lower prices for upstream miners, channel benefits to capital-intensive midstream factories, and leave local governments to handle pollution, land conflicts, and worker safety. This is the complete picture of Indonesia’s nickel policy once we look beyond export totals. It serves as a warning to countries considering rare-earth export restrictions as an easy route to wealth without addressing tougher reforms at home.

China’s Rare Earth Export Restrictions and Soaring Profits

China controls most of the world’s rare earth processing and magnet manufacturing capacity. Recent estimates indicate it accounts for about 90 percent of refining and a similar share of separation and purification, as well as the majority of permanent magnet output. In 2025, it strengthened its grip by adding new rare earth export restrictions to existing quotas and a 2023 ban on exporting key processing technologies. Licenses are now required for exports of selected heavy rare earths and finished magnets. Many products made abroad with Chinese-origin rare earths also need approval. New rules prohibit Chinese engineers from assisting overseas rare earth projects without permission. Concurrently, Beijing has consolidated hundreds of producers into just two large state-owned groups that hold the central mining and separation quotas. These actions give the central government much greater control over who can mine, process, and export rare earths, and under what terms.

The domestic rewards for large companies have been significant. Industry data show that a widely watched rare-earth price index rose by around 40 percent between late 2024 and mid-2025, signaling a sharp price rebound. The benchmark concentrate price for a major light rare earth producer also surged from about 16,700 yuan per ton in the third quarter of 2024 to over 26,000 yuan per ton in late 2025, marking an increase of more than 50 percent. Based on these prices, one leading company reported more than 40 percent revenue growth and about 280 percent net profit growth in the first three quarters of 2025. Another firm saw its net profit rise by almost 200 percent over the same period. Unlike Indonesia’s nickel miners, who faced lower domestic prices after the export ban, China’s consolidated rare-earth groups are enjoying substantial profits from export restrictions and strong global demand.

These profits conceal a more brutal reality for many miners and communities. Years of consolidation and stricter regulations have closed numerous small mines and informal operations. New management regulations for rare earths, enacted in 2024, require companies to track rare earth movements, meet state-set quotas, and report data regularly, placing the entire sector under a much tighter security-focused framework. Recent enforcement actions have shut down unlicensed sites in the interest of safety and ecological protection. Studies and journalism reports severe contamination in major mining areas, with toxic waste damaging soil and water, raising concerns about long-term health risks. Simultaneously, disruptions in rare-earth supply from neighboring Myanmar, where rebel forces control key heavy rare-earth deposits, have put additional pressure on legal mines in China and raised prices for elements like terbium. The domestic landscape that supports rare-earth export restrictions comprises a small number of state-backed firms with pricing power. At the same time, many workers and residents struggle with job insecurity and ongoing environmental damage.

The main point is that China’s rare earth export restrictions now serve three functions. They act as a bargaining chip in trade disputes. They direct high-value exports toward preferred industries and partners. They also discipline domestic producers through quotas, licensing, and technology controls. Each of these functions has clear winners and losers within China. Export licenses and technology rules determine which firms survive, which regions thrive, and which mines close. However, most policy discussions still highlight Western vulnerability and global supply diversification. This emphasis obscures domestic costs, including jobs lost when a region is rezoned, farmers who lose access to clean water, and small processors pushed out of the quota system.

Policy Lessons: Managing Domestic Costs of Rare Earth Export Restrictions

What should policymakers, educators, and industry leaders learn from these stories? The first lesson is that rare earth export restrictions represent domestic industrial policy as much as foreign policy. In both Indonesia and China, value is shifted among miners, processors, manufacturers, and the state. Evaluating them solely for their ability to elevate a country in the value chain overlooks their internal consequences. A more honest assessment should start with three questions: Who will experience price changes? Who will gain bargaining power in new licensing and quota systems? Who will be left handling long-term environmental damage?

The second lesson is that export leverage can diminish faster than local harm. China’s dominance in rare-earth processing and magnets provides strong short-term power, but responses elsewhere are growing. Public programs and private investors in the United States, the European Union, Japan, and Australia are funding mines, separation plants, and magnet factories. Recent industry analysis indicates that non-Chinese supply could account for roughly 35 to 40 percent of global rare earth output by 2030 if planned projects succeed. If that occurs, the price surge currently benefiting Chinese profits may decrease. Research on Indonesia’s nickel policy also suggests that greater domestic value added can occur alongside lower average productivity, as small, inefficient firms enter protected downstream sectors. Export bans can thus leave countries with ingrained inefficiencies and damaged environments just as their leverage over buyers begins to weaken.

For educators and analysts, this calls for a change in how critical minerals are taught and discussed. Courses on global economics and development should use rare-earth export restrictions as case studies of domestic bargaining under international pressure, rather than solely as instances of trade conflict. Universities in resource-rich regions can gather detailed data on jobs, wages, health, and environmental quality before and after export measures are implemented. Their findings can help steer national debates beyond simple export values and corporate earnings. They can share stories from Baotou, Sulawesi, or Myanmar alongside graphs of prices and trade flows.

For policymakers, the practical steps are straightforward in principle, even if challenging in practice. Any new round of rare earth export restrictions should include domestic safeguards. These should feature clear rules for quota allocation, minimum wage, and safety standards in mining and processing, targeted support for workers and communities facing job losses or pollution, and independent pollution monitoring with regular public reports. Rare-earth export restrictions will remain attractive as demand for magnets and batteries continues to grow. Indonesia's experience shows that increased domestic value does not automatically ensure shared benefits. Without safeguards, the primary winners will be a small group of large firms and political insiders. At the same time, miners, residents, and future generations bear the burden.

Time horizons also present a key issue. Export restrictions often arise during heated geopolitical disputes, but their domestic impacts unfold over decades. In China’s rare earth sector, consolidation into two giant state-owned groups and the introduction of technology and export controls have already changed who mines, processes, and profits. In Indonesia, the nickel ban has locked in a development pathway dominated by large factories and foreign investment, with only modest poverty reduction in affected districts thus far. Suppose critical minerals are to support a fair energy transition. In that case, policies must treat miners and local communities as central stakeholders rather than collateral damage in broader trade strategies. Rare earth export restrictions are likely to persist. The fundamental policy challenge is whether governments can convert this moment of strategic advantage into lasting shared prosperity at home rather than allowing domestic inequality to deepen under the guise of national security.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Baskaran, G., & Schwartz, M. (2025). China’s new rare earth and magnet restrictions. Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Bosker, M., van den Herik, E-M., Pelzl, P., & Poelhekke, S. (2025). The (un)intended consequences of export restrictions. VoxEU/CEPR.

Discovery Alert. (2025). China’s rare earth magnet dominance: Strategic risks and global responses.

International Energy Agency. (2025). Critical minerals policy tracker: Regulations on the Management of Rare Earths (China, 2024).

Kee, H. L., & Xie, E. (2025). Nickel, steel and cars: Export ban and domestic value-added in Indonesia (Policy Research Working Paper 11249). World Bank.

Kim, O. (2025). Indonesia climbs the chain: Nickel, industrial policy, and poverty reduction. Global Developments.

Longbridge / WallstreetCN. (2025). Rare earth “dual heroes”: Performance soars in 2025.

Rare Earth Exchanges. (2025). Rare earth processing 2025 – Global capacity and key players.

U.S. Geological Survey. (2024). Mineral commodity summaries 2024: Rare earths.

Yale Environment 360. (2025). In Myanmar, illicit rare earth mining is taking a heavy toll.

Reuters. (2025). Myanmar rebels disrupt China rare earth trade, sparking regional scramble.

Comment