From Monopoly to Membership: Recasting China's Rare Earth Strategy

Input

Modified

China’s rare earth strategy is shifting as Western supply chains rapidly diversify Beijing can trade short-term leverage for long-term alliances built on stable access Educators and policymakers should treat rare earths as a core case in managing interdependence

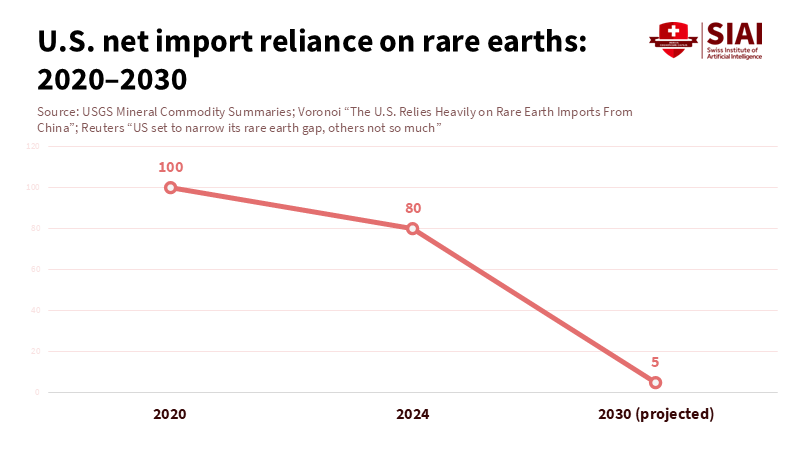

Currently, nearly seven out of every ten tonnes of rare earth ore mined globally come from China. About 70 percent of U.S. rare earth imports between 2020 and 2023 also originated there. This concentration underscores China's strategic importance, making it vital for policymakers and industry leaders to recognize the potential risks and opportunities involved. However, the political landscape surrounding China's rare earth strategy tells a different story. In late October 2025, Beijing announced a one-year suspension of new export controls on rare earth minerals and magnets. During this same period, Washington reduced its steep tariffs and extended key license exclusions. Together with a surge of new projects in the U.S., Europe, and allied producers like Australia, this truce feels more like a countdown than a pause. Within one or two years, crucial parts of the Western magnet and defense supply chains could run with significantly less reliance on Chinese materials. The key question is whether Beijing will take this opportunity to increase pressure or turn rare earths into a foundation for long-term leadership.

China's rare earth strategy is at a crossroads

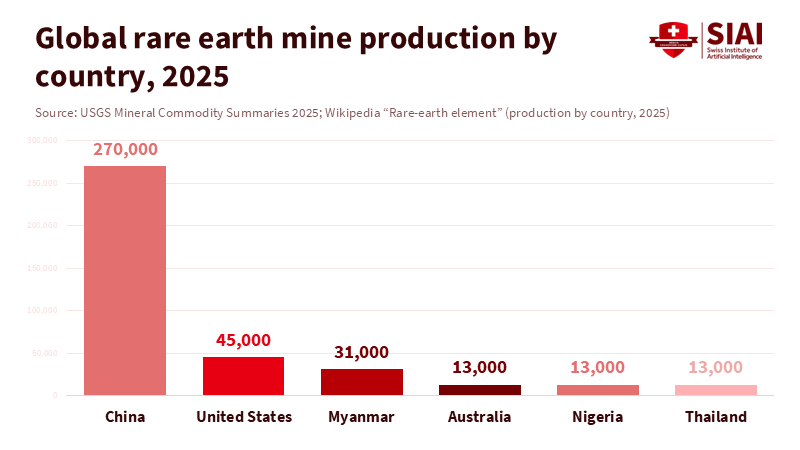

China's rare earth strategy has relied on scarcity. In 2024, China produced about 69% of global rare-earth mine output, totaling around 270,000 metric tonnes, while the United States produced only about 45,000 tonnes. For years, over two-thirds of U.S. rare-earth imports came directly from China. This reliance has allowed Beijing to signal, and sometimes implement, export controls as a foreign policy tool. The new trade truce ensures rare earths will flow for a year, but it also highlights the shifting foundation of that leverage. Recognizing this evolution is crucial for policymakers and educators to understand the changing dynamics of global resource power. What was once a quiet tool is now at the forefront of diplomacy. This rarely signals strength; it usually indicates that leverage is close to peaking.

Meanwhile, the foundation for that leverage is changing quickly. In Nevada, MP Materials has increased its neodymium-praseodymium output and is building a magnet plant that aims to produce around 10,000 tonnes of permanent magnets per year, matching total U.S. magnet demand in 2024. In Malaysia, Lynas has improved its refining hub, expanded its capacity for NdPr-family elements, and is entering heavy rare earth processing with Japanese partners. France has approved Europe's first integrated plant for the separation and recycling of rare earths. EU-funded projects like HARMONY and REEPRODUCE are also testing closed-loop magnet recycling on a small scale. If these initiatives stay on track, by the late 2020s, the United States could meet most of its rare-earth demand domestically or through trusted partners, even though China will still supply the majority of global output.

This is where the short-term politics of China's rare-earth strategy and the one-year truce become relevant. Projections suggest that by 2030, the United States could meet about 95 percent of its rare-earth needs from domestic sources, while still relying on China for over 90 percent of heavy rare-earth processing. Western policymakers are viewing this shift as an urgent priority rather than a distant possibility. The trade deal provides China with a year in which rare earth exports appear stable again, just as capital and technology begin to flow into competing supply chains. What Beijing decides to do during this year will impact whether rare earths remain sources of tension in Washington and Brussels or become part of a more stable framework for shared security and green industry.

China's rare earth strategy as a tool for alliances

There are two paths for China's rare earth strategy: a hard approach and a smarter one. The hard path views the one-year pause as a tactical timeout. In this perspective, Beijing keeps rare earths as a potential threat, reinstates tight controls once new Western capacity comes online, and attempts to use scarcity to slow down the decoupling process. While this approach may provide short-term bargaining power, each use of that power encourages investment in alternatives. This pattern has been evident in previous rounds of export restrictions and in the sweeping limitations announced in early October 2025. Each drastic action encourages more governments and companies to diversify, even at greater costs. Over time, the success of this tactic undermines its own foundation.

The smarter path treats rare earths as a chance for cooperation rather than just a bargaining tool. Beijing is already testing this idea in the broader field of green minerals, where it has proposed an international cooperation initiative with nearly 20 resource-rich developing countries under a new 'green minerals' framework. A similar shift in China's rare earth strategy toward advanced economies would leverage the current window to secure co-investment, technology partnerships, and shared stockpiles with the United States, Europe, Japan, and other advanced economies. Instead of threatening to cut supply, China would offer long-term contracts based on transparent pricing, traceability, and environmental standards. This approach fosters trust and stability, encouraging policymakers and industry stakeholders to see a future of shared benefits rather than conflict.

The comparison with artificial intelligence (AI) is notable. In open-source AI, Chinese labs have moved from being behind to taking the lead. A recent study based on Hugging Face download data shows that Chinese open models now represent a slightly larger share of global downloads than U.S. models, even though U.S. companies still dominate proprietary systems. Chinese firms like DeepSeek and Alibaba's Qwen provide advanced open-weight models quickly and affordably, with DeepSeek launching new architectures that reduce training and inference costs while maintaining performance. Venture capital experts now caution that "open-source AI is China's game right now," which poses a strategic challenge for the West. By releasing accessible systems into the global market, Beijing has transformed code into a tool of influence rather than control. A more generous China rare earth strategy could employ a similar approach in the physical space: offer reliable access, embed Chinese standards and technologies in global factories, and encourage others to think carefully before severing ties.

China's rare earth strategy and the next generation of policymakers

For educators and policy schools, China's rare earth strategy is no longer a niche subject for mining experts. It is a current case study in how materials, technology, and power intersect. Students preparing for roles as officials, engineers, or social scientists will step into a world where the rules for critical minerals remain unsettled. Courses that once treated resources as a static backdrop now need to engage learners with dynamic topics such as export controls, price floors, green subsidy races, advances in recycling, and community resistance to new mines. Rare earths demonstrate that politics does not simply occur after technical decisions are made. Politics influences which technologies receive funding, where facilities are located, and how long monopolies can endure.

This has direct consequences for curriculum design. Law and public policy programs can use the ongoing trade truce as a simulation, prompting students to draft alternative futures for China's rare-earth strategy based on varying assumptions about U.S. self-sufficiency. Engineering and business schools can connect technical training on magnet design with discussions on supply chain ethics and geopolitical risks. International relations courses can compare rare earths with open-source AI, exploring where the analogy holds and where it falls short. Across these learning environments, the goal is not to portray China as the villain or the West as the victim; instead, it's to prepare students to analyze interdependence. They must understand how today's tactical agreements can either limit or expand future opportunities for cooperation.

Policymakers and administrators face their own learning curve. Many still cling to oversimplified narratives: bring all supply chains home, reduce reliance on strategic rivals, and treat every chokepoint as a weapon. Yet, evidence regarding rare earths and AI reveals a more complex situation. The West will reduce its vulnerability to China in certain areas but not eliminate it. Heavy rare-earth processing is likely to remain centered in Chinese or China-linked facilities well into the next decade, even as U.S. mines and allied refineries expand. Meanwhile, China cannot overlook the costs that strict export controls impose on its reputation and its own manufacturers, who depend on stable international markets. A more cooperative approach to China's rare earth strategy does not mean abandoning national interests. Instead, it entails recognizing that lasting influence depends on being viewed as a dependable partner, not just a powerful one.

The main criticism of this argument is that it fails to account for the inertia of existing systems. Critics will point out that new mines require years to obtain permits, finance, and build; that rare-earth recycling is still in pilot stages; and that many Western projects may falter. They will also argue that China has strong reasons to maintain environmental and social stability at home by controlling the most polluting stages of rare earth production. All of this is valid. However, it strengthens the case for a strategic shift. Exactly because China will continue to hold a significant position in rare earths and green minerals, it can exchange some immediate leverage for deeper alliances. A stable, rule-based approach would simplify planning investments for both sides and help universities prepare graduates for the kinds of cross-border projects that clean energy, defense, and digital infrastructure will require.

A second critique is that the analogy with open-source AI may extend too far. Rare earths are heavy, environmentally damaging, and politically sensitive. In contrast, code is lightweight, easily replicated, and less tied to specific locations. Nevertheless, both fields reveal the limitations of strict control. In AI, a recent U.S. government study found that leading American models still outperform key Chinese competitors across many benchmarks, even as Chinese open-source models are catching up in terms of cost and availability. In minerals, while China currently dominates production, it struggles to convert that dominance into lasting goodwill. A forward-thinking China rare earth strategy would acknowledge that others will diversify and instead focus on guiding how that diversification unfolds. This means choosing collaboration over unexpected setbacks and establishing institutions where technical standards, safety measures, and environmental safeguards are negotiated rather than imposed.

The final test is time. A decade from now, the striking figure that opened this column will almost certainly have changed. China will likely remain the largest producer of rare earths, but its share of global output is expected to decline. The United States and its allies will likely control a greater portion of magnet production and recycling. What will matter then is not whether China once held 69 percent of the market, but whether it used that opportunity to deepen distrust or to foster new patterns of cooperation. Educators, administrators, and policymakers can influence this choice by prioritizing China's rare earth strategy as a key teaching and policy issue today. The one-year truce between Washington and Beijing should not be viewed as a break; instead, it should be seen as a chance to shape a different future. If this invitation is taken seriously, rare earths can transform from a symbol of zero-sum rivalry into a testing ground for a more stable and informed global order.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

China Briefing. 2025. “China’s Rare Earth Elements: Dominance in Global Supply Chains.” August 29, 2025.

Council on Foreign Relations. 2025. “United States and China Agree to Trade Truce.” October 30, 2025.

Financial Times. 2025a. “China’s Li Pushes Developing Country Alliance on Rare Earths.” November 24, 2025.

Financial Times. 2025b. “China Leapfrogs US in Global Market for ‘Open’ AI Models.” November 26, 2025.

HARMONY Project. 2025. “HARMONY’s Mission: Recycling Rare Earth Elements for a Circular Economy.”

Hinrich Foundation. 2025. “The US Makes a Big Move to Test China’s Rare Earth Dominance.” August 26, 2025.

Interconnects (Lambert, N.). 2025. “On China’s Open Source AI Trajectory.” September 9, 2025.

Keystone Procurement. 2025. “Sustainable Sourcing of Rare Earth Materials.” May 16, 2025.

Lynas Rare Earths. 2025. “Malaysia Operations: Strategic Global Processing Hub.” October 7, 2025.

MP Materials. 2025. “MP Materials Reports Third Quarter 2025 Results.” November 6, 2025.

REEPRODUCE Project. 2025. “Dismantling and Recycling Rare Earth Elements from End-of-Life Products.” November 11, 2025.

Reuters. 2025a. “US Set to Narrow Its Rare Earth Gap, Others Not So Much.” November 25, 2025.

Reuters. 2025b. “DeepSeek Releases Model It Calls Intermediate Step Towards Next Generation.” September 29, 2025.

Science|Business. 2023. “Weighing the Attractions of Recycling Rare Earth Magnets.” July 11, 2023.

Taglieri, L. 2025. “Made in Europe: Recovery of Rare Earth Elements.” Procedia CIRP.

Tom’s Hardware. 2025. “U.S. Commerce Sec. Lutnick Says American AI Dominates DeepSeek, Thanks Trump for AI Action Plan.” October 2025.

U.S. Geological Survey. 2025. “Mineral Commodity Summaries 2025: Rare Earths.”

Washington Post. 2025a. “U.S. Rare Earth Ambitions Center on Malaysia. But China’s Already There.” November 21, 2025.

Washington Post. 2025b. “China Now Leads the U.S. in This Key Part of the AI Race.” October 13, 2025.

Comment