The Taiwan Bargaining Chip Is Now Industrial Policy

Input

Modified

Taiwan’s advanced chips make it a bargaining chip in U.S.–China–Japan rivalry Tariffs, subsidies, and new fabs turn semiconductor leverage into day-to-day industrial policy Education must build chip literacy and procurement buffers to withstand supply shocks

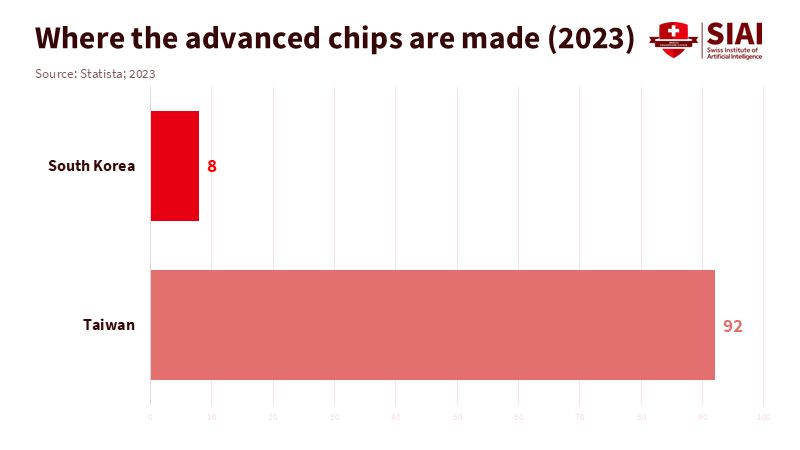

A single fact defines the risk this decade: Taiwan produces most of the world's most advanced logic chips. This concentration is critical for AI, data centers, and modern weapons systems. It is also central to the rivalry between the U.S. and China. The outcome is not just words. It is leverage. It is the "Taiwan bargaining chip." Washington now talks about tariffs, production ratios, and “on-shore or else.” Tokyo emphasizes subsidies, economic security, and factory openings in Kyushu. Beijing sees both as pressure. When a technology choke point drives growth, it becomes the policy. And Taiwan is that choke point. This is why the discussion over deterrence has merged with a struggle over fabs and supply chains. It explains why every summit headline now reflects a semiconductor theme. It is also why education systems should view chip policy as essential civic knowledge, not just a part of industrial policy.

The Taiwan bargaining chip: from metaphor to policy

Seeing Taiwan as a bargaining chip is no longer just a metaphor; it is a strategy. It is now a daily tool in trade talks, alliance politics, and domestic messaging. This view solidified in 2025 as the White House combined tariffs and summit meetings with indications that support for Taiwan could change with the current deal. News coverage and analysis revealed a pattern: increase the economic stakes, suggest concessions, then adjust the pressure based on Beijing’s response. Markets recognized this shift. So did Taipei. In late October, U.S.–China discussions at APEC coincided with tariff actions and signals about technology flows. Reports suggested some levies would decrease while others would remain. This showed how security and trade now operate together, with Taiwan positioned between them. This is the practical application of the Taiwan bargaining chip.

Critics argue this is just bluster. They claim any president who openly sacrifices Taiwan would lose Congress and public support. There is some truth in this. Public opinion and elite consensus tend to be hawkish on China and supportive of Taiwan. Analysts highlight the political cost of a visible “trade-away.” However, even without an explicit sacrifice, the day-to-day transactional approach creates uncertainty. It encourages businesses to hedge. It leads allies to secure their own options. It also gives Beijing reasons to probe for inconsistencies between words and commitments. The chip is used not only in the final agreement; it plays a role in the process. This is what Taipei fears. This urgency drives Congress, Tokyo, and Brussels to turn statements into concrete timelines, provide guarantees, and build collaborative capabilities. The headline pledge matters, but the effort behind it matters even more.

How semiconductors turn leverage into law

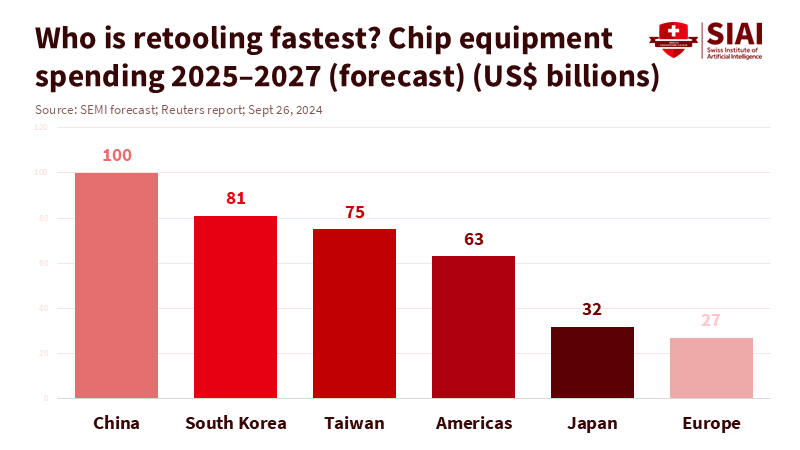

The bargaining chip had a significant impact once fabs became part of U.S. law. The CHIPS and Science framework transformed risk reduction into funding, tax credits, and procurement. It also turned a single company into a strategic hinge. TSMC’s U.S. expansion received a multibillion-dollar award in 2024. By January 2025, officials were celebrating the initial runs of 4-nanometer production in Arizona, with a pathway for next-generation nodes later in the decade. The explicit policy goal is to capture a significant share of leading-edge capacity by 2030, where the U.S. previously had very little. This strategy mixes money, rules, and messaging. It tells allies: come build here. It tells Beijing: our choke points won’t stay in one place forever. And it informs businesses: align your supply plans with the subsidy and tariff maps.

The rhetoric goes even further. Senior officials have suggested ratios that would require chip makers to balance domestic production with imports or hinted at strict production splits for the U.S. market. Taiwan has publicly pushed back against this. Industry analysts have also raised concerns about these numbers, pointing out the challenges of quickly relocating supplier ecosystems. Yet this is the point: the discussions themselves serve as leverage. They influence decisions today, even if the goals are years away. For Taiwan, the risk is clear. Suppose the U.S. demands increased domestic output while China maintains high trade barriers. In that case, Taipei must grow at home while helping allies expand abroad. This dual requirement is costly. It also reinforces the perception that Taiwan’s principal value to Washington is leverage over China through semiconductors. The Taiwan bargaining chip essentially becomes the foundation for policy.

Japan’s play: economic security, Kumamoto, and quiet signaling

Japan has adopted a different tone with a similar goal. It has integrated a chip strategy within “economic security” and funded concrete projects. Tokyo supported TSMC’s first Kumamoto plant and allocated billions more for a second fab that will start operating later this decade. The message is quiet yet firm: embed Taiwan’s ecosystem within allied territories, connect suppliers to Kyushu, and regard resilience as a form of national defense. Prime Minister Fumio Kishida’s visits and speeches at these sites emphasize that this work is both about alliances and industry. This approach also signals to Beijing without causing drama while establishing facts on the ground. If Taiwan is the bargaining chip, Japan’s strategy is to hold part of it by hosting it.

Tokyo’s second approach is Rapidus—the domestic push towards next-generation nodes with collaborations in the United States and Europe. This project is part of a broader economic security law and a METI strategy that channels substantial subsidies into advanced manufacturing and packaging. The goal is not to outpace Taiwan instantly. Instead, it is to ensure that, if a crisis occurs—or if political leverage shifts—Japan can maintain a minimum viable supply for its automotive, robotics, and defense sectors. For Beijing, this effort looks like containment. For Washington, it signifies burden-sharing. For Taipei, it represents both a lifeline and a concern: a lifeline because allies will keep purchasing and co-investing; a worry because every wafer produced outside Hsinchu slightly weakens the “silicon shield.” The overall effect is to normalize Taiwan's bargaining chip as shared infrastructure rather than a single point of failure.

What educators should do when the Taiwan bargaining chip moves

Education systems must pay attention to this landscape. The use of AI in classrooms relies on chips and cloud technology. If supply becomes tight, device refresh cycles will slow, and software costs will rise. Planning should account for supply disruptions, not just price fluctuations. Universities and technical colleges should expand semiconductor curricula to include policy knowledge, including export controls, trusted foundry models, and related standards. Teacher training programs should incorporate basic chip and supply-chain knowledge into civic education. Students should graduate able to interpret a tariff headline and understand its impact on a school’s IT plan. This is practical, not abstract, because procurement cycles are lengthy and budgets are constrained when hardware costs soar.

Research policy should adopt the same level of realism. Cross-border lab partnerships will face more compliance requirements and delays. Funding sources should include secure compute access and contingency plans if a provider faces sanctions or a facility outage. National agencies can assist by publishing shared advice for ed-tech buyers on assessing “resilience claims” from vendors—what their contracts entail, which nodes they depend on, and where they package. Moreover, when public funding supports AI in education, grants should evaluate compute costs per learner under both normal and constrained chip-supply conditions. This approach turns the Taiwan bargaining chip from a potential risk to a bargaining factor.

Administrators also have a role to play. School systems can push suppliers to disclose dependencies and geographic distribution in simple terms, allowing boards and parents to understand the exposure. They can prioritize vendors who diversify fabrication and packaging across allied locations. Additionally, they can participate in consortium purchases to secure capacity in advance. None of this requires taking sides in politics. It requires treating the chip policy as a utility policy for digital learning. Suppose we keep saying AI will transform teaching. In that case, we must also prepare for the costs and availability of the silicon that drives it. The Taiwan bargaining chip is not only about ships in the Strait. It is about laptops and classroom learning time.

Anticipating the critiques

Skeptics may argue that the “bargaining chip” perspective exaggerates the risk. They highlight that Washington has strong political incentives not to trade away Taiwan and that deterrence still functions. They are correct about the incentives, and surveys support their views. However, incentives do not eliminate uncertainty. They do not erase tariff shocks, delayed deliveries, or ambiguous statements that influence capital and policy. Deterrence can coexist with transactional bargaining. In fact, this is the balance we currently experience. The responsibility for educators and policymakers is not to weigh intentions in Washington, Beijing, or Tokyo. Instead, it is to create safeguards against a policy approach that impacts markets through public statements. This starts with recognizing the power of the Taiwan bargaining chip and budgeting for its movements.

The world’s most advanced chips still cluster on one island. This reality is not changing quickly, even as facilities in Arizona and Kyushu are being developed. It provides Washington with a tool—a plan for Tokyo—and a grievance for Beijing. It also presents a planning challenge for schools and universities. We should not dismiss this challenge as niche. Every digital learning promise relies on silicon. Every procurement depends on nodes and locations. The appropriate response is not panic; it is literacy and safeguards. Teach students and boards the significance of Taiwan as a bargaining chip. Secure contracts that spread risk. Reward vendors who are transparent and diversify. Support research that considers computing as an essential input with a real cost. And keep teaching, even as headlines change. The best way to mitigate leverage is to reduce vulnerability to it. This is the role of education in a world where industrial policy also equates to security policy—and where Taiwan, like it or not, remains the bargaining chip that drives the market.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

AP News. (2024, November 15). Biden administration announces $6.6 billion to ensure leading-edge microchips are built in the U.S.

East Asia Forum. (2025, November 4). Trump’s transactionalism turns Taiwan into a bargaining chip.

FPRI — Foreign Policy Research Institute. (2025, May 27). Why Trump won’t sacrifice Taiwan.

Japan METI. (2024, July). Outline of Semiconductor Revitalization Strategy in Japan.

Quartz. (2025, September 29). Trump wants Taiwan to move half of its U.S. chip supply to America. Don’t count on it.

Quartz. (2025, October 1). Taiwan says 1:1 chip split did not come up in recent U.S. trade talks.

Reuters. (2024, February 6). TSMC to build second Japan chip factory, raising investment to more than $20 billion.

Reuters. (2024, February 24). Tokyo pledges a further $4.9 billion to help TSMC expand Japan production.

Reuters. (2025, January 10). TSMC begins producing 4-nanometer chips in Arizona, Raimondo says.

Reuters. (2025, March 31). TSMC affirms commitment to Taiwan with new domestic fab amid overseas expansion.

Reuters. (2025, October 30–31). Taiwan talks trade with U.S. at APEC; progress reported though tariffs persist.

U.S. Department of Commerce — NIST. (2024, November 15). CHIPS incentives award to TSMC Arizona.

CSIS — Center for Strategic and International Studies. (2024, January 5). Previewing Taiwan’s 2024 presidential election (note on Taiwan producing ~90% of advanced chips).

BBC News (Live page). (2025, October 30). Trump lowers “fentanyl tariff” after talks with Xi.

Comment