The Grab GoTo Merger and Competition: Regulate Scale, Not Just Size

Input

Modified

Grab–GoTo could control ~85–90% of ride-hailing, risking lock-in Approve only with guardrails—data portability, fair access, pricing caps, driver-earnings floors—or block Educators and ministries should bake these rules into procurement and curricula

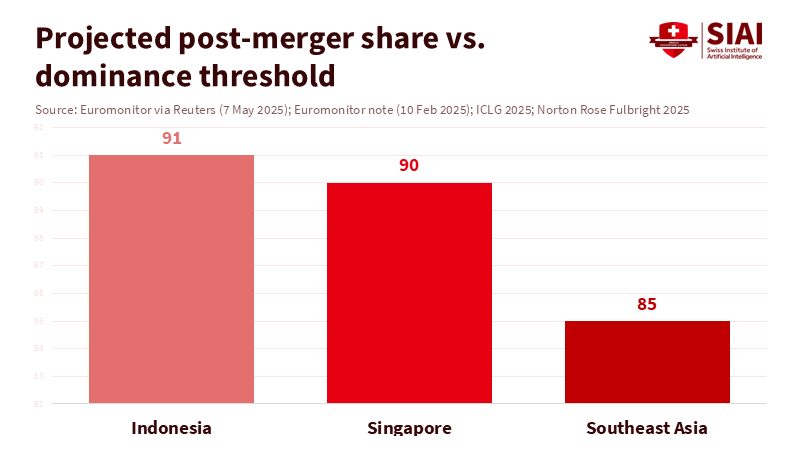

One key number should guide this discussion: 85-90%. If Grab and GoTo merge their mobility and delivery networks, the new company could control about 85 percent of Southeast Asia’s ride-hailing Gross Merchandise Value (GMV) and around 90 percent in key markets such as Indonesia and Singapore, according to recent reports. This is not just a standard efficiency move; it represents a significant shift that poses real risks for riders, drivers, restaurants, and small businesses. Singapore’s competition authority has already set guidelines on dominant ride-hailing mergers, having penalized Grab-Uber and imposed measures to maintain competition. Indonesia’s regulator has outlined the legal standards that trigger scrutiny. At the same time, the region’s digital economy is rapidly expanding—expected to reach US$263 billion in GMV by 2024, a 15 percent increase year-over-year—so the stakes grow with each quarter. The takeaway is straightforward. Scale can be beneficial. Unchecked dominance can lock up markets. The goal is to maintain the benefits of scale without encouraging market control.

Why the Grab GoTo merger debate matters now

The Grab GoTo merger challenges governments to balance two conflicting goals: fostering regional champions and keeping markets open. Southeast Asia needs firms that can invest on a large scale in AI, logistics, and payments. However, a deal that results in 90% control over the core market could reduce price competition, slow innovation, and lower driver incomes. Indonesia’s KPPU assumes that a firm is dominant at 50% alone and at 75% for two or three firms. This assumption is crucial because it shifts the burden of proof. These firms must demonstrate that real competition will persist and that consumers and small businesses will benefit, not just shareholders. The agency has indicated it is currently assessing risks related to a potential deal. Singapore’s CCCS, which has been asked for guidance, has noted it has not yet received a formal notification but will take action if competition weakens, as seen in the 2018 Grab-Uber decision. The context is a regional platform market that is still consolidating, where effective remedies—not just slogans—determine outcomes.

Synergy claims are credible. A merged firm could combine driver resources, improve dispatch, reduce unnecessary trips, and offer financial and insurance products. It could also eliminate duplicate costs in cloud services, customer support, and compliance. These savings can lead to lower prices or higher profits—or both. The issue is how these gains are distributed in a highly concentrated market. In May 2025, driver groups across Indonesia protested low wages. They expressed concerns that a merger would push earnings down as rates increase. In a market with two large networks, drivers can switch between services when incentives change. However, in a market dominated by one player, that flexibility disappears. This data does not prove harm, but it serves as a warning: when options diminish, labor pressure tends to increase. A remedy-first approach is not anti-growth; it ensures that the benefits of scale do not come at the expense of those who keep the network running.

Dynamic competition exists, but it is not guaranteed

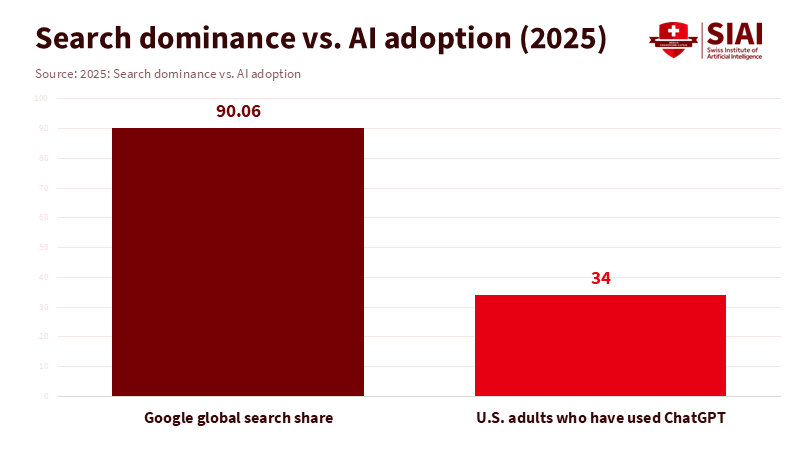

One counterargument suggests that market dominance can vanish quickly in tech. Proponents cite search engines as an example: AI tools can shift user habits in a matter of months. While there is some truth to this, a core reality in search remains hard to ignore: Google holds about 90 percent of the global search engine market. Established systems with deep habit loops, default settings, and distribution advantages change slowly. In ride-hailing and delivery, these advantages include payments, fraud prevention, merchant integration, driver onboarding and safety checks, and airport and mall pickup slots. The reality is that while dynamic entry is possible, it does not happen automatically. It requires an environment that permits it—through data access, portability, and fair access to vital connections—especially if one firm nears ninety percent post-merger.

The same trend is evident in Southeast Asia’s platform data. Analysts estimate that the Grab GoTo merger would control about 85 percent of regional ride-hailing and over 90 percent in Indonesia, its largest market. These figures may vary by method, but the trend is clear: a single network would overshadow competitors like Maxim or inDrive. This is why Indonesia’s watchdog emphasized legal thresholds and initiated risk assessments even before any formal filing, and why Singapore’s past cases are essential. In 2018, the CCCS found that the Grab-Uber merger harmed competition, raised fares, and required penalties and behavioral remedies to restore market dynamics. Agencies recognize that these markets are tightly integrated. They also understand that remedies are most effective when crafted before competition intensifies.

A remedy-first approach for the Grab GoTo merger

The policy choice is not simply to approve or block based on market share alone. It is about approving with safeguards, or blocking if those safeguards cannot function effectively. The safeguards should address the specific issues that make it difficult to compete in mobility and delivery markets. First, require data portability and rights for riders, drivers, and merchants to switch platforms. Users should be able to export trip histories, ratings, and preferences via standard APIs to enable easier multi-homing. Second, demand fair, non-exclusive access to critical resources—such as pickup points at airports or malls. Third, impose temporary limits on prices and fees: set clear caps on commission rates and surge pricing above a set baseline for a defined period, such as 24 months, with a sunset clause that activates when an independent competitor reaches a market share threshold. This mirrors an earlier CCCS approach, which conditioned the easing of rules on a rival achieving a sustained 30 percent share of rides. These targeted measures maintain flexibility while keeping markets open during the merging firm's integration.

Fourth, establish minimum earnings for drivers. When regulators permit a merger that elevates concentration beyond dominance levels, they should require the platform to set effective hourly wage floors and transparent rules for deactivations and penalties. This ensures service quality and reduces turnover, which could negatively impact consumers. Fifth, mandate clarity in algorithms related to fairness: clear, verifiable documentation on how dispatch, dynamic pricing, and incentive budgets function. The intent is not to disclose proprietary secrets; it is to enable regulators to verify claims about efficiency and benefits. Sixth, approach cross-market bundling cautiously. Suppose the merged company also manages financial services, such as wallets or insurance. In that case, it should not link rides or deliveries to these financial products in a way that sidelines competitors. Indonesia’s regulations already view a high market share as a warning sign for monopolistic risks; these practical assessments translate into everyday oversight. If such safeguards are denied or manipulated, the case for blocking the merger becomes stronger.

Finally, prepare for measured divestitures if the behavioral safeguards cannot maintain competition. This might involve selling city clusters, specific sectors (such as grocery delivery), or logistics assets in markets where the new firm exceeds stable dominance thresholds. Divestiture is not a sign of strategic failure; it is often the most effective way to revive competition and sustain pressure for innovation. None of this prevents industrial policy. Regions can still support champions, promote cross-border payments, and advocate for AI research. However, these goals should complement competition rather than undermine it. The best approach is conditional approval with strict, clear rules that protect users and workers while leaving room for future challengers.

What educators and policymakers should do now

Education leaders will be affected by the outcome of the Grab GoTo merger, regardless of regulators' decisions. Universities, vocational schools, and educational systems extensively use platform services, providing transportation for students, food delivery, and logistics for campus events. The first step is to enforce procurement discipline. Link campus contracts to data portability, open APIs, and fair-access terms for pickup locations. Vendors should disclose fee structures and honor their ratings if a student or merchant switches apps. This is not just theory; it reflects the remedies that agencies have implemented in prior ride-hailing cases and aligns campus needs with competitive practices. Systems that establish these terms now help shape markets going forward.

Second, update educational content. Schools of public policy, business, and law should teach “competition within industrial policy” using current examples from Southeast Asia. Students should model how benefits are transferred under high concentration, simulate how data portability affects customer churn, and test surge-pricing caps against driver-earnings minimums. They should study why established players in search remain strong despite advancements in AI—34 percent of U.S. adults have used ChatGPT, yet Google maintains around 90 percent of the market—then consider what that implies for mobility, where defaults and logistics play a more significant role. A good course will engage students in how design choices—APIs, access rules, and disclosures—materialize into genuine competition, rather than merely in theory.

Third, establish a regulatory lab focused on platforms. Ministries can bring together regulators, companies, and researchers to test standard frameworks for driver data, universal rules for pickup zones near schools and hospitals, and methods for auditing pricing algorithms. The lab can explore how different fee controls affect wait times and driver availability, and publish results that provinces can implement. This logic parallels efforts that enhanced payment systems across ASEAN. The digital economy’s projected US$263 billion size gives ministries leverage; through clear trials, this leverage can create norms that persist beyond any single merger cycle. If the deal is blocked, these labs remain valuable. If it proceeds, they become crucial.

The critical figure—85 to 90%—is a caution, not a conclusion. The Grab GoTo merger could facilitate cost savings and faster growth. However, it could also create obstacles and harm those with less bargaining power. History in search shows us that dominance can persist even amid technological changes. Case law in Southeast Asia illustrates how specific remedies can protect space for competitors and consumers. The necessary action now is explicit. Regulators should insist on data portability, fair access to critical nodes, transparent pricing guidelines, and minimum driver earnings as conditions for any approval. They should implement straightforward deadlines tied to genuine competitor market share. Educators and administrators should incorporate these rules into procurement processes and classroom discussions, translating policy into real-world applications. If the safeguards are inadequate, agencies must be prepared to reject the merger. If they are sufficient, the region can enjoy the benefits of scale without sacrificing future competition. This is how we can create a digital economy that grows while remaining fair, one regulation at a time.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Bain & Company; Google; Temasek. (2024). economy SEA 2024 (Report PDF).

Competition and Consumer Commission of Singapore (CCCS). (2018, September 24). Infringement decision and directions in Grab-Uber merger (case register and media release).

East Asia Forum. (2025, July 3). Grab’s acquisition of GoTo is a big test for Indonesia’s competition regulators (op-ed).

East Asia Forum. (2025, November 4). Who benefits from picking digital winners? (op-ed).

Euromonitor International. (2025, February 10). Three key implications of the Grab and GoTo merger (analysis note). Norton Rose Fulbright. (2025). Indonesia competition law fact sheet (dominance thresholds: 50% single; 75% two-three firms).

Pew Research Center. (2025, June 25). 34% of U.S. adults have used ChatGPT, about double the share in 2023.

Reuters. (2025, February 4). Grab and GoTo in advanced merger talks, sources say. https://www.reuters.com.

Reuters. (2025, March 19). Singapore competition watchdog says no guidance yet on Grab, GoTo merger plans.

Reuters. (2025, May 21). Indonesia’s antitrust body looking into risks from reported Grab-GoTo merger.

Reuters. (2025, May 20). Ride-hailing drivers in Indonesia hold protests to demand better pay.

StatCounter Global Stats. (2025, October). Search engine market share worldwide (Google ~90%).

Comment