The Fixed-Cost Trap: Why Housing Support Unlocks Higher Savings

Input

Modified

High housing costs lock households into hand-to-mouth budgets and suppress saving Targeted housing support and expanded affordable supply free cash for productive spending and learning Prioritize urban renters, index aid to rents, and track overburden rates monthly

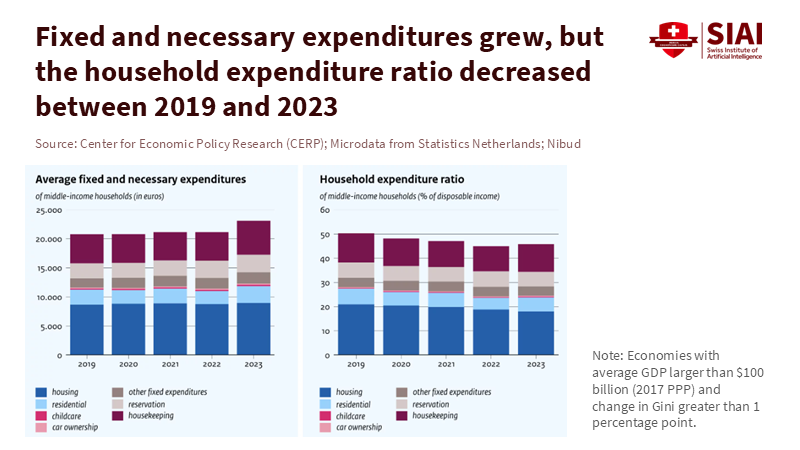

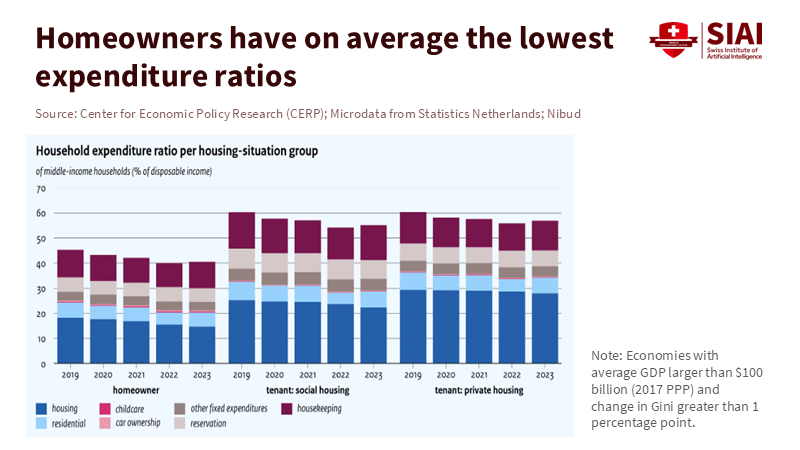

In the Netherlands today, almost half of market-rate renters spend over 40% of their disposable income on housing. This fact reshapes our understanding of household saving. When a fixed bill takes up nearly half of a family's income, there is no room for flexibility. Families can cut back on groceries or hold off on purchases, but rent is due every month. New evidence from Dutch household budgets between 2019 and 2023 shows that fixed and necessary spending increased by about €2,000 in 2023, mainly due to rising energy and food costs, even as disposable incomes also rose. Homeowners faced a lower fixed-spend ratio than renters, with private renters bearing the heaviest burden. The trend is clear: where fixed costs dominate, savings stagnate, even when earnings increase. To encourage more saving and spending, we need to reduce fixed burdens. This is why housing support is not just an extra; it serves as a crucial tool for mobility.

Housing Support and the Fixed-Cost Trap

Economists typically categorize households into two types. Some save consistently from their extra income. Others live paycheck to paycheck, using what comes in because they have little savings. In prosperous economies, the second group is sizable, accounting for about a third of households. This group includes many people with assets but little cash on hand. When we look at housing data, the fixed-cost trap emerges. In the EU in 2023, households spent about 19.7% of their disposable income on housing. In cities, more than one in ten people lived in homes where housing costs exceeded the 40% threshold. For those already close to this limit, it feels more like a cliff than a line. Housing support—through rent allowances, affordable housing, or targeted relief—helps turn this fall into a slope.

Dutch statistics clarify the mechanics. On average, people in the Netherlands spend 23% of their disposable income on housing, which is among the highest shares in Europe. This average, however, hides a significant divide. Urban households face a much greater risk of being overburdened than their rural counterparts. Private-market renters are particularly stressed. For them, overburden rates are very high. When a policy reduces even a small part of that fixed weight, the money tied to rent can instead go toward saving, skills, or a child's laptop. At the macro level, decreasing fixed costs improves the saving rate where it counts the most.

The main takeaway is straightforward. Suppose fixed costs anchor behavior, then cutting those costs frees it up. Housing support achieves this by reducing housing-related budget allocations and stabilizing monthly cash flow. The result is not just a higher saving rate; it also leads to better consumption, including energy-efficient appliances, healthier food, and paid course materials. In essence, flexible budgets lead to productive choices. This connection between social policy and growth is key.

How Fixed Costs Shape Saving Rates

Recent Dutch microdata shows the relationship between fixed and necessary spending by housing type. Homeowners use about 42% of their income on these essentials, while tenants spend roughly 57%. The difference is not about being stingy; it reflects structural issues. Private renters spend about the same amount on essential items as homeowners, but a significantly larger share of their income goes to housing costs. In 2023, fixed expenses increased by about €2,000 compared to 2019-2022, driven mainly by energy and food costs. When basic bills rise, no budgeting tricks can provide flexibility. Housing support, designed for renters and delivered quickly, creates the space for savings to begin.

There is also a dynamic story behind the averages. From 2018 to 2023, household incomes in the Netherlands grew faster than housing costs. Private-market tenants experienced the most significant income growth—about one-third over five years—yet they remain the most vulnerable. This segment has grown since 2018 and is at the heart of the overburden risk. This highlights an essential point for policy: while income growth is necessary, it is not enough when fixed costs are high. To change saving behavior, the policy must directly target the fixed expenses. Housing support acts as the precise tool we need.

Looking at the bigger picture, the macro data aligns with model predictions. A substantial share of hand-to-mouth households—often around 30%—amplifies the impact of fiscal and housing policies on spending. Lowering fixed housing costs helps households escape cash constraints. It decreases the portion of income that must be spent each period. The outcome is a higher savings buffer and a broader base of savers. This is how housing support transforms a tool for distribution into one for growth.

What Works: Housing Support as Productive Policy

International advice is clear. First, increase the supply of affordable and social housing to ease price pressure. Second, direct subsidies to households facing the most risk, particularly private renters. Third, make the private rental market more affordable by balancing tenant protections with incentives for long-term investment. These elements form a solid housing support strategy. They facilitate saving by directly reducing fixed costs. They also minimize volatility, since rent can be a shock when prices rise but remains a stable expense when prices fall.

Evidence from health and social policy boosts the economic argument. Reviews of housing support models—such as housing-first, tenancy support, and assisted living—show savings and better outcomes, even when financial assessments are incomplete. Fewer hospital visits for older adults, more stable independent living, and smoother transitions from care are common benefits. These are not just minor advantages; they define public value. When a rent supplement or a supported tenancy prevents a crisis, public budgets can avoid costly emergency responses. Those savings can then be allocated to education, skills, and family support. Housing support is, in effect, a productivity policy.

For the Netherlands, the policy map is clear. Overburden mainly affects market-rate renters, especially in urban areas. Data show that urban housing costs significantly outstrip those in rural areas. This is where new housing, focused allowances, and cost-saving standards yield the most benefits. The OECD’s report on the Dutch economy emphasizes the need to increase affordable rental options while maintaining investment incentives. Aligning housing support with these supply-side strategies quickly reduces overburden, lowers fixed costs, and boosts savings.

Design Rules for Educators and Policymakers

Education leaders should view housing support as part of the learning structure. When students and families have stable housing, attendance and focus improve. Across Europe, the rising cost of living has forced many young adults to remain at home longer. It has severely impacted student budgets, especially in areas where rent exceeds available support. Reports from statistical offices and research institutes highlight increasing accommodation pressures, which lead to more absences, stress, and a higher risk of dropouts. Housing needs to be included in the strategy for student achievement. It is not a distraction from learning; it is essential for it.

What should universities and school systems do? Begin with targeted stipends or emergency grants linked to local rent levels. Work with local governments to expedite student access to housing support programs and social housing waitlists where possible. Where institutions control housing, they link rents to maintenance loans or to student needs rather than to seasonal market rates. Education departments can test “housing-linked maintenance” that provides extra support when rent inflation exceeds student aid. This is not a shift in mission; it aligns with it. Research on housing quality and children's well-being is also clear: poor living conditions can negatively impact mental health and behavior. Ensuring stable housing, then, is a vital part of the learning environment.

National treasuries should prioritize high-impact areas. Increase the availability of affordable rental homes in cities where overburden is a significant issue. Enhance the targeting of housing support so that the most critical amounts reach market-rate renters facing the highest fixed costs. Provide temporary relief during price spikes, but phase it out as markets stabilize. The goal is not to subsidize shortages; it is to eliminate them. This message aligns with the OECD’s approach. Supply and support must move in tandem, or we will create a fixed-stock bottleneck. When done correctly, the outcome will be a significant reduction in overburden, higher household savings, and more effective spending on education and health.

The opening statistic isn't just a trivial fact. When nearly half of market-rate renters in a wealthy country spend more than 40% of their income on housing, the savings issue is clear. It’s not a mystery of choices; it’s a matter of simple math. Fixed costs restrict buffer savings. That is why housing support should be central to economic policy. It helps break the fixed-cost trap, nudges families living paycheck to paycheck towards saving, and frees up cash for investments in essentials—like books, devices, transportation, and training. We need to pair targeted support for renters with a push for affordable housing supply. We must align education policy with housing stability. We should monitor overburden rates just as we track unemployment. If we take these steps, the consumption-income curve will flatten as it should. Families that struggle to save today will be able to do so. And the public will see benefits each month, as more households can save while still meeting their rent obligations.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

ABN AMRO Research. (2025, April 30). Housing market monitor: EU housing markets share common problems.

CBS (Statistics Netherlands). (2024, May 28). Housing costs in the Netherlands higher than in most EU countries.

CBS (Statistics Netherlands). (2025, June 5). Share of income spent on housing fell between 2018 and 2023. Retrieved November 5, 2025.

Eurostat. (2024). Housing in Europe — 2024 edition.

Eurostat. (2025). Housing cost overburden rate (tespm140/tessi164).

Kaplan, G., Violante, G. L., & Weidner, J. (2014). The wealthy hand-to-mouth. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity.

OECD. (2021). Building for a Better Tomorrow: Policies to Make Housing More Affordable. Paris: OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2025). OECD Economic Survey: Netherlands — Towards a more accessible and sustainable housing market.

UK Collaborative Centre for Housing Evidence (CaCHE). (2024, February). The economic and social benefits of housing support. Glasgow: CaCHE.

van der Plaat, M., & Huizinga, A. (2025, November 4). Dutch households spend less of their income on fixed and necessary expenditures. VoxEU/CEPR.

Comment