U.S. Leadership in Asia Isn't Collapsing. It's Consolidating

Input

Modified

US leadership in Asia is consolidating, not fading Japan, Korea, Taiwan, and key ASEAN partners are tightening defense and tech ties with Washington This hardening coalition outweighs rhetoric and is reshaping education and industry

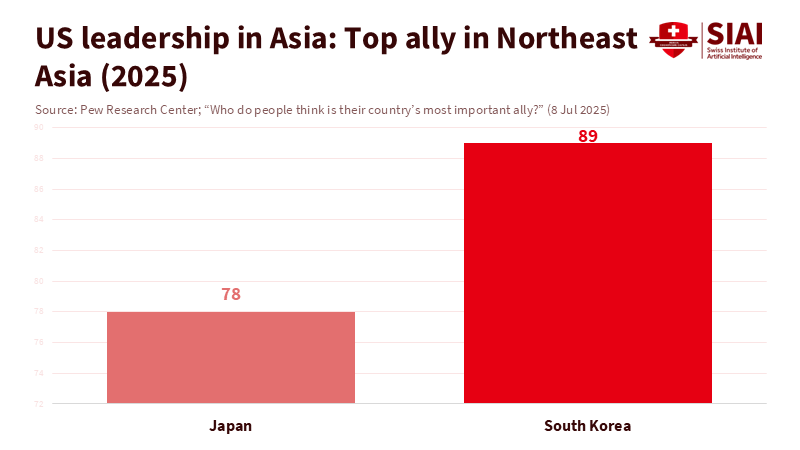

One data point cuts through the noise. In 2025, over 80% of South Koreans identified the United States as the world's top economy. This view, based on real experiences and complex data, reflects trust in direction and capability. It also suggests where U.S. leadership in Asia is headed. If leadership is just about speeches, then Washington's domestic conflicts are indeed a setback. However, if leadership focuses on forming coalitions that can prevent war, share risks, and manage crises, then look north of the Tropic of Cancer. Japan and South Korea have strengthened their partnerships with the United States in defense, technology, and intelligence sharing. Include Taiwan's ongoing, though uneven, defense upgrades and key Southeast Asian partners like the Philippines and Vietnam, and a trend emerges: U.S. leadership in Asia has not diminished; it has concentrated where it counts the most. The coalition is stronger, quicker, and more unified than it was five years ago.

U.S. leadership in Asia is consolidating in the north

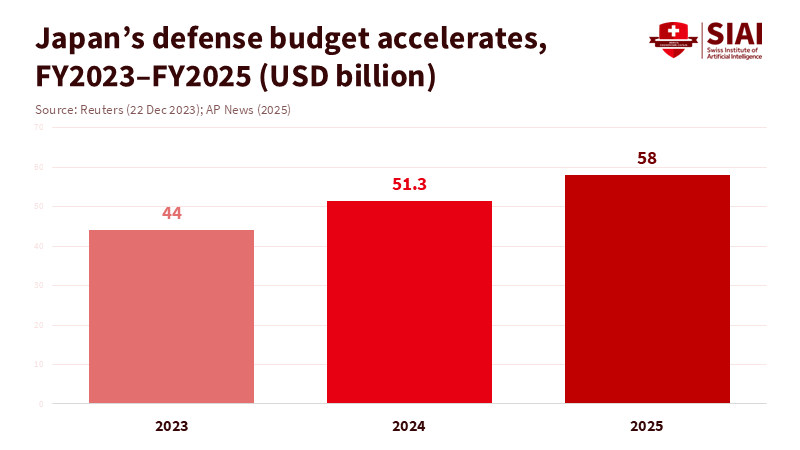

Start with deterrence. Since the Camp David summit in August 2023, Washington, Tokyo, and Seoul have transitioned from occasional cooperation to a structured partnership. They now hold annual leader meetings, commit to consultations, and crucially, share real-time missile warning data that is already operational. While that technical detail may sound dry, it carries political weight. It means these three nations can see, decide, and act together when North Korea launches missiles. Shared warnings reduce decision-making time and connect militaries at the sensor level, not just on paper. Japan has also demonstrated its commitment by approving a record 8.7 trillion yen (USD 58.3 billion) defense budget for 2025, aiming to spend close to 2% of GDP on defense. Public opinion supports this: majorities in both Japan and South Korea have a favorable view of the U.S., especially in South Korea. U.S. leadership in Asia is not just talk; it is firmly established in upgraded hardware, shared software, and consistent public support.

Tokyo and Seoul are also training alongside the U.S. like never before. The new trilateral multi-domain exercise, Freedom Edge, launched in 2024 and expanded in 2025, builds coordination across air, sea, cyber, and missile defense domains. Everyone involved understands the message. Exercises clearly demonstrate that allies can operate together from day one, not after lengthy planning. When cooperation becomes this detailed, and when warning data is shared in real time, deterrence doesn't rely on speeches or who is in the Oval Office. It depends on whether partners can move in sync. That sync is now established in Northeast Asia.

China's coercion is strengthening the coalition

Coalitions form under pressure. This is evident in the South China Sea. A Philippine sailor sustained serious injuries in June 2024 when Chinese forces blocked a resupply mission near Second Thomas Shoal. Washington responded publicly and specifically: attacks on Philippine armed forces or vessels, including coast guard assets, would activate U.S. treaty obligations. A month earlier, the U.S., Japan, and the Philippines released a joint statement condemning aggressive maritime tactics and promising practical projects to enhance capabilities. This diplomatic stance is supported by tangible actions: access to nine Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement sites in the Philippines, increased funding for upgrades at those sites, and the largest-ever Balikatan exercises in 2024. Manila has shifted from hedging to aligning with the U.S. This shift was not based on speeches from Washington; it resulted from confrontations at sea. U.S. leadership in Asia grows when local leaders perceive that the risks of going solo outweigh the risks of partnering with the U.S.

Vietnam tells a quieter version of this same trend. In September 2023, Hanoi and Washington upgraded their relationship to a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership, a designation Vietnam previously reserved for a select few major powers. One year later, both nations reported progress on semiconductors, digital trade, and supply chains. Vietnam will maintain its strategic autonomy. However, it is leaning towards the U.S. regarding technology and market access while managing its relationship with China. By 2025, regional opinion leaders shifted back towards viewing Washington as ASEAN's preferred partner after a brief decline in 2024. The center of gravity in Southeast Asia may not be fixed. Still, pressure at sea and the need for resilient supply chains have pushed several key capitals closer to the U.S. orbit. This represents coalition-building incrementally: a port agreement here, a training exercise there, a rules-based statement following a confrontation, and a growing consensus that joint resilience is better than silence.

Security, technology, and supply chains are becoming intertwined

Security partnerships are increasingly linking to technology and industrial policy. The April 2024 US-Japan leaders' statement prioritized economic coercion, trusted supply chains, and advanced manufacturing in the alliance. Trilateral US-Japan-ROK cooperation has brought shared missile warnings, multi-year exercise plans, and more frequent defense consultations among ministers. Taiwan presents a challenging situation; it lies at the intersection of all three areas. In 2023, the U.S. utilized the Presidential Drawdown Authority to transfer a $345 million package from military stockpiles for the first time, and in 2024, a significant air defense sale was approved. Although there are real delivery delays, and lawmakers want to speed things up, the direction is clear: Taipei is acquiring Abrams tanks, HIMARS, and air defenses, and deepening its training with the U.S. In short, the operational readiness of the region's coalition is improving, gradually but surely, across both military and industrial fields.

Japan's budget initiatives, South Korea's operational integration with the U.S. and Japan, and Taiwan's procurement plans form the backbone of this coalition. Surrounding this backbone are supporting elements: US-Philippine basing access and improvements; trilateral coast guard coordination; and investments focused on reducing risks rather than on decoupling. The technical aspects—air defense integration, real-time data sharing, distributed bases, and repeated training—are significant because they can be quantified, tested, and verified by allies and adversaries alike. U.S. leadership in Asia now relies less on the U.S. taking the lead and more on the U.S. supporting a collective effort. This cooperation can endure through political changes as long as it is seen as a regional safeguard against unilateral use of force.

The Trump factor and the reliability issue

An obvious counterargument is about reliability. Public trust in the U.S. fell sharply in Australia in 2025, and analysts in Canberra express concerns that alliance commitments could drag Australia into an unwanted conflict. This caution is essential. Yet, in Northeast Asia, the trend has been different. South Korea and Japan have intensified defense coordination with the U.S. and with one another, despite changes in leadership and election-related noise in Washington. Trust in American democracy may fluctuate without disrupting essential security ties, particularly when facing coercion alone. In 2025, majorities in Japan and South Korea still favor the U.S., and many South Koreans see it as the leading economy. For decision-makers and educators, the practical lesson is clear: legitimacy is now measured in spreadsheets and schedules—who funds, who trains, who participates—rather than in applause at public events.

There is also an uncomfortable reality for critics: Trump's visit to Asia this autumn did not break the coalition; in some areas, it strengthened it. South Korea hosted a grand ceremony in his honor, presenting him with the nation's highest award and a replica gold crown in Gyeongju. Japan maintained strong connections in areas like deterrence and technology. Meanwhile, US-Japan-ROK drills continued, and Washington reaffirmed its commitments to Manila and Tokyo. The tone can be debated, but the facts on the ground—active data sharing, expanded exercises, rising budgets, and existing access agreements—have not changed. If anything, they have intensified under pressure. U.S. leadership in Asia remains credible because allies are investing in it even when U.S. politics seem unstable.

This has direct implications for education systems, not abstract ones. Universities and vocational schools should incorporate Asian security and technology literacy into their general education and executive programs. Coalition dynamics now influence labor demand across sectors such as semiconductors, shipbuilding, cybersecurity, and logistics. Teacher training programs should update civics, geography, and media literacy curriculum with case studies on the South China Sea and the US-Japan-ROK framework to highlight how rule-making and deterrence actually function. International offices should shift mobility and research partnerships toward Japan, South Korea, and the Philippines while ensuring academic freedom is protected in China, where cooperation is essential. Ministries must align scholarships and micro-credentials with growing sectors—air defense manufacturing, maritime safety, critical minerals, and AI safety—to match workforce needs with the new regional economy. School leaders should prepare for an influx of exchange students from these partner nations by investing in language instruction (Japanese, Korean, Filipino) and student support services that navigate complex political climates both at home and abroad. U.S. leadership in Asia will be evident in classrooms through enrollment shifts, internship opportunities, and research grants long before it appears in textbooks.

Addressing critiques—and responding to them

The first critique argues that the U.S. is too divided to lead anything. The counter to this is institutional: the coalition's key upgrades since 2023 are technical and budget-focused, not just rhetorical. Real-time missile warning systems are now operational. Tripartite exercises are scheduled. EDCA sites have been established and funded. Japan's budget is committed to a long-term increase. These developments are not merely speeches; they represent systems and funding mechanisms that outlast any news headline. U.S. leadership in Asia today is a shared network; it depends on established infrastructure.

The second critique claims Southeast Asia favors China. This held some truth in 2024 surveys, but the 2025 data shows a return to a preference for the U.S. as a partner. More importantly, strategic choices are not either/or. Manila has decisively shifted toward Washington due to immediate pressures in the maritime domain. Vietnam has strengthened ties with the U.S., where it sees the most benefit—technology and supply chains—while maintaining diplomatic space. This is how medium powers balance their interests, and it is how coalitions deepen over time. Educators should view the region as a case study in practical pluralism: partnerships can vary by sector, and the mix evolves as risks change.

The third critique suggests that allies are concerned about being drawn into conflicts, particularly Australia. This concern is valid; trust dipped in 2025. The solution is to ensure coalition actions remain defensive, transparent, and anchored in law. It's crucial for Washington to publicly clarify that treaty commitments are clear—attacks on armed forces and vessels, not every confrontation at sea. It is also essential that exercises focus on interoperability and casualty evacuation rather than regime change. Furthermore, it is important for discussions about allied budgets and basing to occur in open parliaments. In the classroom, this means teaching students to distinguish between deterrence and provocation using primary documents, not just opinion pieces.

The simplest way to understand the region is also the most evidence-based. A coalition centered on Japan, South Korea, and the United States has activated systems that integrate sensing, training, and funding at a pace that seemed unlikely a few years ago. The Philippines has shifted from hedging to alignment under direct pressure at sea. At the same time, Vietnam has upgraded ties in ways that matter for its growth. Public sentiment in Northeast Asia supports this trend; Japan is investing to make it sustainable. Even as trust falters in Australia, the core alignment has solidified. Grand gestures, such as presenting a gold crown in Gyeongju, should not overshadow the foundational mechanisms at work. That infrastructure is why U.S. leadership in Asia appears more like a focused effort rather than a fading influence. The current task is to invest in the human resources that will sustain it: educational programs that build coalition literacy, partnerships that promote student and idea exchanges, and research that contributes to regional safety and prosperity. The coalition is established. Education systems should adapt to it.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

AP News. (2025). Japan cabinet OKs record defense budget as it pushes strike-back capability to deter regional threat.

Biden White House Archives. (2023). Fact Sheet: The Trilateral Leaders’ Summit at Camp David.

Biden White House Archives. (2024). Joint Vision Statement from the leaders of Japan, the Philippines, and the United States.

Japan Ministry of Foreign Affairs. (2024). Joint Statement of the Security Consultative Committee (“2+2”).

Nippon.com. (2024). Japan’s defense budget rising toward NATO target of 2% of GDP.

Pew Research Center. (2025). Views of the United States.

Reuters. (2025). South Korea awards Trump its highest medal, gifts him a golden crown.

State Department (U.S.). (2024). U.S. support for the Philippines in the South China Sea.

The ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute. (2025). The State of Southeast Asia 2025 Survey Report.

U.S. Department of Defense. (2023). United States–Japan–Republic of Korea Trilateral Ministerial Joint Press Statement (missile warning data sharing).

U.S. Embassy & Consulates in Vietnam. (2024). United States and Vietnam: Building on the momentum of the Comprehensive Strategic Partnership.

U.S. Indo-Pacific Command. (2024). Trilateral statement: First execution of multi-domain Japan–ROK–U.S. exercise Freedom Edge.

USNI News. (2024). Philippine sailor severely injured as Chinese forces block South China Sea mission.

War College/DoD. (2023). New EDCA sites named in the Philippines.

White House (U.S.). (2025). United States–Japan Joint Leaders’ Statement.

White House (U.S.). (2023). The Spirit of Camp David: Joint statement of Japan, the Republic of Korea, and the United States.

Comment