Short-Video Nationalism: Viral War Dramas Are Cheap Politics with High Costs

Input

Modified

Short-video nationalism is entertainment-driven but spreads grievance fast When it targets Japan, boycotts and tourism losses impose real costs Teach short-form literacy and use narrow, transparent rules to curb harms

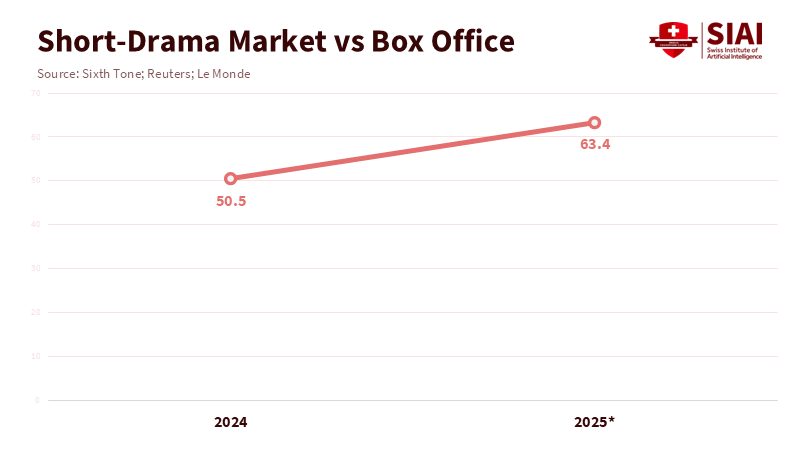

A single figure shapes the discussion. China’s short-drama market hit 50.5 billion yuan in 2024, surpassing the national box office for the first time. Growth is expected to reach 63.4 billion yuan in 2025. This surge is driven by micro-episodes designed for quick viewing—rapid revenge plots, intense emotions, and easy sharing. In short, short-video nationalism has become a popular form of entertainment, not just a niche propaganda tool. The content often engages with wartime memories, occasionally in an absurd way. It also faces domestic regulatory criticism, even as viewers continue to watch. This should ease some concerns: the priority is still on the spectacle akin to TikTok. However, there's a downside. When viral storytelling exaggerates enemy portrayals—especially of Japan—it can lead to real boycotts, declines in tourism, and stalled policies. Those repercussions outweigh any quick political gains. Educators and policymakers do not need a culture war over phones. They need a strategy that cools tensions while improving historical learning and media literacy.

Reframing the Argument: short-video nationalism is spectacle, not a state agenda

We should not assume that every viral clip is part of a larger plan—the attention market rewards shock and quickness. Short dramas thrive because they deliver these elements. Platforms and producers notice what works and scale it up. The state takes notice and sometimes responds with patriotic campaigns; it also attempts to control the worst excesses. In July 2025, China’s broadcasting regulator cautioned against absurd war storylines and introduced stricter oversight for wartime short dramas. Reports that month highlighted dozens of releases in just a few months, racking up hundreds of millions of views. The issue is not that censors control everything. It is that the political system reacts to a commercial trend it didn’t create and can’t completely manage. This trend—fast, adaptable, and meme-friendly—better explains the format’s reach than any singular propaganda theory.

This conflict appears in memory politics. Official commemorations aim for solemnity and narrative control. Viral videos seek popularity, even if a 1944 drone suddenly appears on the front line. Analysts have shown how the Party has tried to shape the memory of the war through educational efforts and curated media. However, the ultra-short format challenges that model. When attention, rather than accuracy, is the focus, memory turns into a playground. Regulatory pushback arises because the spectacle can sometimes trivialize the very history that official narratives seek to honor. In short, short-video nationalism leans on market incentives that overlap only partially with the state’s objectives. This makes it chaotic and, at times, flashy, but not centrally directed. The spectacle is genuine; the connection to policy is not.

The real price tag: trade, tourism, and trust

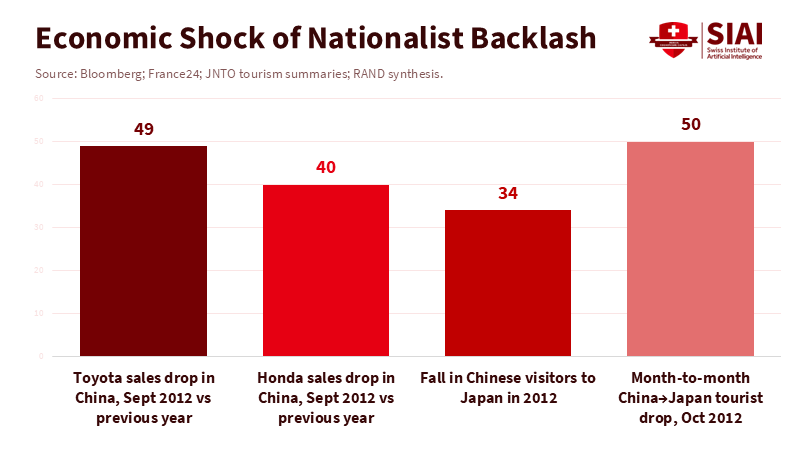

If the politics are inexpensive, the consequences are not. We've seen this before. During the 2012 conflict over the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands, Japanese car sales in China plummeted: Toyota dropped by about 49%, and Honda fell by about 40% in September. This decline reflected boycotts, fears of vandalism, and a reluctance to display Japanese brands publicly. Tourism also took a hit. The number of Chinese visitors to Japan decreased by 34% in 2012, with a nearly 50% drop from September to October. These are real losses for both supply chains and service sectors. They also outlast any viral trend. Economic ties rebuild slowly once consumer trust is broken.

Extensive research since then explains why these shocks hurt. Studies of the 2012 boycotts reveal that most of the sales drop was due to cancellations rather than simple brand switches. In straightforward terms, people didn’t choose a rival car—they stopped buying cars altogether. This impacts output and jobs in China, as many Japanese-brand vehicles are produced in Chinese factories with local suppliers. Broader studies on political boycotts in China show how nationalist movements disrupt trade, investment, and tourism in ways that linger. Short-term approval gains at home are offset by stalled agreements, investment holdups, and damaged city economies that experienced protests. Minor disruptions add up to a sustained drag on growth and regional trust.

What’s actually different now: scale, speed, and short-video nationalism

Two new factors change the risk assessment. First, the scale of mobile video is enormous. Chinese micro-dramas represent an industry worth $5–7 billion annually by 2024–2025, with audiences in the hundreds of millions. Global platforms like TikTok surpassed 1.0 billion monthly users worldwide in 2024. In 2025, reports suggest more than 660 million micro-drama viewers in China alone—about half of all internet users. The implications are clear. A mood shift that used to spread through prime-time TV now ripples through a constant feed. This doesn’t turn the content into a propaganda factory. However, it means that a framing mistake or an outrage-inducing story can spread quickly and reach more people, including students, before educators can respond.

Secondly, speed shortens the gap between content and consequences. Research on consumer boycotts in China from 2008 to 2021 documents 90 incidents targeting foreign companies. The newer incidents are organized and amplified online. Viral calls to “buy national” or “cancel trips” can arise within hours, outpacing the slower, measured statements that diplomats prepare. Even if officials prefer to maintain low tensions for economic reasons, online feeds can rapidly boost public sentiment. In this environment, short-video nationalism acts as a catalyst. It makes it easier for low-cost political messages to resonate and harder for long-term interests to prevail in the moment. The result is a policy dilemma: leaders can ride the wave for a brief approval boost, or they can endure political challenges now to prevent economic harm later.

A more thoughtful response for educators and policymakers

Treat the cultural trend as entertainment with side effects. Don’t ban it; set boundaries. In schools and universities, this means incorporating short-form analysis into history and civics classes. Students should learn how to analyze framing, recognize anachronisms, and verify clips against sources in two languages whenever possible. They should also understand why narratives can become entrenched around grievances and how those grievances spread through algorithms. None of this requires scolding students about phones. It demands teaching how short videos work: shot-reverse-shot for moral alignment, jump cuts for escalation, cliffhangers for retention. This is how we create a filter that sticks when the next viral story appears. Educators will have better success with this strategy than with blanket warnings that resemble another culture war.

Policy should focus on reducing tensions and improving communication. Governments in the region can provide clear, specific guidance for platforms on misleading war content that impersonates official statements or manipulates archival footage without labels. Regulators should enforce visible provenance tags on historical clips and advocate for cross-platform communication channels so ministries can promptly flag harmful forgeries. Importantly, do not center policy on a single offending platform. The behavior spreads across different ecosystems. It’s better to set outcome rules—on disclosure, remix labeling, and takedown speed—than to chase the latest app. This keeps the focus on harms rather than symbols that voters tend to protect.

Keep the politics cheap—and the diplomacy expensive—in perspective

The hardest choice is to show restraint. It is tempting for leaders in China or Korea to stoke anti-Japan sentiment when poll numbers decline. The short-term benefits are real. However, the regional history is clear: boycotts hurt exports, damage local industries, and reduce travel. South Korea’s 2019 anti-Japan backlash prompted a domestic backlash as business costs rose. China’s 2012 protests caused visible damage and enduring commercial fallout, which researchers have documented in corporate outcomes and tourism statistics. None of this created lasting power; it wasted cash and trust. If we desire stability—and growth that covers social needs—governments should model composure. They should view short-video nationalism as a cultural trend to navigate, not as a weapon to wield. Leave the cinematic emotions to the duanju studios. Reserve national policy for the careful work of trade, study abroad, and joint historical projects that yield benefits long after a viral trend passes.

The initial figure still matters: 50.5 billion yuan and rising. This is the scale of the short-drama economy, which now features much wartime storytelling. It captures the essence of this argument. Short-video nationalism is a commercial spectacle with political fragments, not a scripted agenda. As entertainment, it is engaging and occasionally silly. In politics, it is inexpensive. But the consequences, when public sentiment spills into protests or affects purchasing decisions, are substantial—lost sales, vacant hotel rooms, delayed investments, and another year of sluggish progress on regional trust. Educators can mitigate the worst outcomes by teaching students how the format functions and where it misrepresents history. Policymakers can target harms, not platforms, and keep open crisis communication channels. The message is clear: stop turning viral dramas into state narratives. Invest in the steady, unexciting work of building ties—classroom to classroom, city to city—so a viral story cannot derail an entire region. That is how we keep phones enjoyable, politics serious, and diplomacy focused on the future, not the trends.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Barwick, P. J., Pan, L., & co-authors. (2023). Commercial Casualties: Political Boycotts and International Disputes (working paper). Retrieved from Cornell/author webpage PDF.

Bloomberg. (2012, Sept. 17). Protests to hurt Japanese car sales in China, dealer group says.

Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. (2012, Sept. 24). The Economics Behind the China–Japan Dispute.

France24. (2012, Oct. 9). Japanese car sales nosedive in China over island row.

Le Monde. (2025, Aug. 17). Chinese Hollywood races to cash in on the minidramas boom.

Nippon.com. (2014, Aug. 29). Chinese Tourists in Japan: Return of the Big Spenders (JNTO data summary).

RAND Corporation. (2022). Countering China’s Coercion Against U.S. Allies and Partners.

Reuters. (2024, Sept. 21). Low-brow and vulgar? Micro dramas shake up China’s film industry, aim for Hollywood.

Sixth Tone. (2025, July 24). Fantastical, False, and Absurd: Ultrashort War Dramas Come Under Fire.

The Diplomat. (2019, Aug. 8). Voices Grow in South Korea to Oppose Anti-Japan Movement.

East Asia Forum. (2025, Nov. 1). Viral ultra-short dramas are challenging China’s memory politics.

Backlinko (eMarketer summary). (2025, Sept. 2). TikTok statistics you need to know in 2025.

Swedish National China Centre (Kinacentrum). (2022, July 11). Chinese consumer boycotts of foreign companies, 2008–2021.

Comment