Globalization and Inequality: A New Compact for the Remote-Work Era

Input

Modified

Digital services trade is booming, shrinking global gaps but widening domestic ones Remote work and uneven AI adoption heighten wage pressure and regional divides Adopt a compact: wage insurance, sectoral training, portable benefits, and remote-first, AI-literate education

One crucial number should change how we discuss globalization and inequality. In 2024, exports of digitally delivered services reached about US$4.64 trillion, growing faster than trade in goods and making up over half of global services trade. This change is not just a detail in trade statistics. It shows how a software tester in Lagos, a bookkeeper in Cebu, or a support agent in Jaipur can now compete with their counterparts in Detroit or Dublin. Firms must respond to this shift. When competitors cut costs by hiring talent from other countries, it becomes difficult to maintain local wages. The result is familiar: inequality decreases across countries as incomes converge, while inequality within countries becomes more apparent and frustrating. In this context, the issue is not about choosing between open markets and fairness. It is about figuring out how to create a system that keeps trade benefits while sharing them domestically—before people lose their patience.

Globalization and Inequality: From "China Shock" to a Wider Service Shift

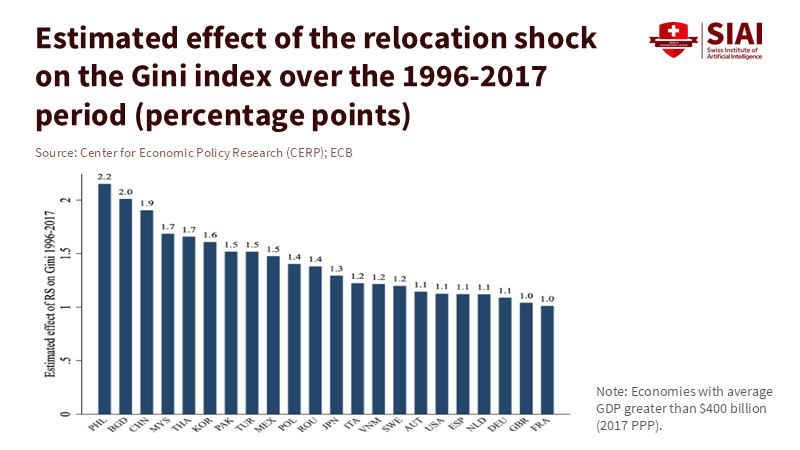

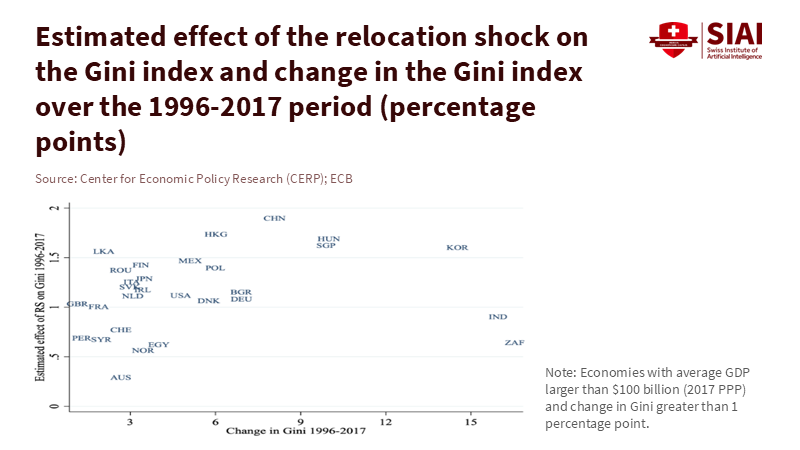

The first wave of recent discussions about globalization and inequality focused on manufacturing. The "China shock" studies showed that import competition from China led to significant and lasting job losses and income declines in various parts of the United States and Europe. These effects continued long after the initial disruptions. This information is important because it challenges the old belief that workers quickly find new jobs after trade shocks. In many areas, they did not. The lesson is not to halt trade but to stop pretending that labor markets always recover quickly. We can expect similar trends as more service jobs become tradable across borders.

Over the past two decades, global inequality between countries has decreased, with fewer economies now considered high-inequality and more moving into lower-inequality groups. This reflects income increases in large emerging markets that have become export leaders. However, within advanced economies, income gaps remain substantial—on average, the richest 10% earn over 8 times as much as the poorest 10% across the OECD. Recent national data also show that inequality pressures have risen in some countries after the pandemic. The simultaneous decrease in gaps between countries and the stubborn gaps within them are the core issues. It explains why globalization appears successful in one chart and strained in another, and why policy must focus on domestic income distribution without hindering international trade.

The second wave is about services. Trade in services reached about US$8.7 trillion in 2024, with digitally delivered services being the most dynamic segment. These are not just high-end exports like cloud computing. They also include payroll, customer support, design, tutoring, and various "office" tasks. This is how the story of Adam and Ananda plays out today. The economics are clear. When a job's output can be sent online, the location of work and local wage standards become disconnected. That is beneficial for global progress, but challenging for local workers competing against a larger talent pool. We've seen this situation with goods trade; now services are following the same pattern.

Globalization and Inequality in a Remote-First Market

Two main factors make this new adjustment challenge different. First, remote work broadens the range of tasks that can be traded. Oxford's Online Labour Index and similar research show a consistent rise in cross-border gigs, with employers sourcing talent from different time zones. This is not a small market; it represents the leading edge of white-collar trade. Second, AI adoption varies among firms. Companies that effectively integrate AI see faster productivity gains and higher pay, while those that do not fall behind. This technology can therefore widen pay disparities within occupations. The combination of remote work options and uneven AI adoption makes local labor markets more competitive and stratified, accelerating the shift of tasks to lower-cost regions or to smaller, more productive teams.

Trade data supports this view. International organizations now estimate that digitally deliverable services make up about 55% of global services trade. Growth rates in 2024 exceeded 8%, outpacing goods trade. Developing economies surpassed the US$1 trillion mark in these exports in 2023, a notable milestone that indicates where new jobs and wages are heading. This does not mean every accounting clerk in Chicago will suffer, or that every coder in Nairobi will benefit. It suggests shifts in relative bargaining power. Hiring managers have more alternative options; workers with rare skills benefit, while those in abundant, routine roles may face downward pressure on wages and job stability.

Regional differences within countries are also likely. Areas with universities, venture capital, and digital infrastructure will attract high-value tasks, while others will face more challenges. This trend resembles the geography of the China shock. Still, policymakers now need to focus on education systems, professional standards, and portable benefits as much as on tariffs or subsidies. If we only look at trade balances, we miss the larger picture. The market has shifted to online platforms, and our new adjustment tools should follow suit.

Globalization and Inequality: A Practical Compact for Workers and Firms

The key question is not whether "Adam" deserves help. It is about creating support that speeds up re-employment, boosts productivity, and keeps companies competitive. Three tools can work together effectively. Wage insurance helps cover income losses when displaced workers take new jobs that pay less, without forcing them out of work. Training tied to employer demand improves earnings in a lasting way. Lastly, portable benefits that follow the worker rather than the job make it easier to switch employers, contracts, or platforms. This approach has a common principle: assistance should follow the person to their next job, not stay tied to their last one. Research from randomized trials in the United States shows that well-designed sector-specific programs can lead to significant, long-term earnings increases for low- and mid-skilled adults by training them to meet, and then clear, hiring-related standards. That is the type of scalable investment we need.

We already have a model for trade-related adjustment, even if it requires improvement. The U.S. Trade Adjustment Assistance program, which lapsed in 2022 and is now being discussed for reauthorization, provides combined training, job search assistance, and income support for workers affected by trade. Its performance varied, but its basic idea—linking resources to confirmed trade displacement—works for the remote-work era with updates. These updates are straightforward: eligibility should include digitally delivered trade displacement in addition to goods, and support should favor earn-and-learn models along with wage insurance to promote quicker returns to work. Other advanced nations can adapt this approach to their labor systems. The goal is not to freeze the market but to make transitions faster and fairer.

Funding this compact should align with economic growth. A small, time-bound public investment in worker transitions can pay off if it helps people move into higher productivity roles. Local support—such as tech hub initiatives or regional partnerships—can succeed when they connect training providers with real job opportunities, rather than focusing solely on generating publicity. The main challenge is not money. It is sticking to a plan: concentrate on programs that show measurable, repeatable earnings improvements, publish results, and eliminate those that do not succeed. Countries that treat adjustment as ongoing infrastructure—updated every year, not just after a crisis—will retain more political support needed to remain open.

Globalization and Inequality: What Schools, Colleges, and Policymakers Must Do Now

Education systems are crucial in this process. If globalization and inequality now intersect through remote services and uneven AI adoption, then curricula, credentials, and career services must evolve accordingly. First, programs should focus on skills needed for remote work: project management across time zones, clear writing, data organization, version control, client communication, and basic cybersecurity. These skills are essential; they define success in distributed teams. Second, AI training should transition from experimental programs to standard practice. Students need repeated opportunities to use AI as a partner and to understand its limitations. This allows them to join the growing number of jobs that will benefit from AI rather than the many that risk being left behind.

Third, institutions should emphasize demonstrating competencies rather than simply spending time in classes. Micro-credentials are effective when three conditions are met: the skill is defined, employers validate the assessment, and the credential contributes to a degree or industry qualification. This stackability is vital because workers frequently change roles as tasks cross borders and new tools emerge. Fourth, career services must focus on placing students in jobs, measured by starting salaries and job retention rates. Partnerships in sectors with actual hiring demand—like health tech, cloud support, digital operations, and advanced manufacturing—are proven paths to better earnings. The emphasis should be on scale and reliability rather than invention.

Policymakers should anticipate resistance. Some may argue that providing adjustment support subsidizes businesses that offshore jobs. Others may assert that open markets will inevitably drive down local wages. Both viewpoints miss the reality. Countries that combine openness with substantial investment in human capital and risk-sharing for workers tend to gain more from globalization while maintaining a broader political coalition for free trade. Those who sidestep either strategy risk moving toward protection without the benefits that usually come with it. The data is precise: services trade is increasing, digitally delivered exports are growing faster than goods, and AI will change the nature of tasks across industries. The issue is not trade versus fairness; it is about thoughtful design versus drifting along.

We started with a number—US$4.64 trillion—that reflects the rapid changes taking place. It illustrates why globalization and inequality feel different today. The focus has shifted from ports to online platforms. If left unmanaged, this change will increase wage disparities within countries, even as gaps narrow between them. However, if we handle it wisely, we can create more opportunities than in any past trade wave. The solutions are within reach: wage insurance for quicker re-employment, sector-based training with employer engagement, portable benefits that follow the worker, and education that prepares for remote work and AI challenges. None of this asks companies to abandon competition. It calls on the government to support quicker learning and safer transitions, enabling people to adapt, switch jobs, and advance. Suppose we want to maintain the benefits of open markets and societal support. In that case, we need to establish that system now—before the next statistic compels us to act.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Autor, D., Dorn, D., & Hanson, G. (2021). On the persistence of the China shock. Retrieved from MIT/UCSD working paper archive.

Dorn, D., & Levell, P. (2024). Labour market impacts of the China shock. University of Zurich working paper.

International Monetary Fund. (2024). Gen-AI: Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Work (Staff Discussion Note). Washington, DC.

J-PAL North America. (2022). Sectoral employment programs as a path to quality jobs: Lessons from randomized evaluations. Cambridge, MA.

OECD. (2024). Society at a Glance 2024: Income and wealth inequalities. Paris.

OECD Statistics Blog. (2025, April 17). 5 things you should know about international trade statistics. Paris.

Oxford Internet Institute. (n.d.). Online Labour Observatory / iLabour Project. Oxford.

Peters, G. (2025, April 14). Trade Adjustment Assistance Reauthorization Act of 2025 [Press release]. Washington, DC.

World Bank. (2024). Poverty, Prosperity, and Planet 2024: Overview. Washington, DC.

World Bank Open Data Blog. (2025, January 29). Declining trends in national inequality. Washington, DC.

World Trade Organization. (2025). Annual Report 2025. Geneva. (Digitally delivered services reached US$4.64 trillion; +8.3% in 2024).

World Trade Organization. (2025). Global Trade Outlook 2025. Geneva. (Global services exports; growth context).

World Trade Organization. (2025, October 7). Trade Outlook Update (news release and statistical note). Geneva. (Projected growth of digitally delivered services).

UNCTAD / Business Standard. (2024, December 8). Developing economies cross US$1 trillion in digitally deliverable services exports. Geneva/New Delhi.

Comment