Power of Siberia 2 and Asia's Energy Price Reset

Input

Modified

Power of Siberia 2 shifts China’s energy risk from tankers to pipelines With Alaska LNG, Asia gains buyer leverage and softer price spikes—not an oil crash Winners will master contract design, sanctions exposure, and long build timelines

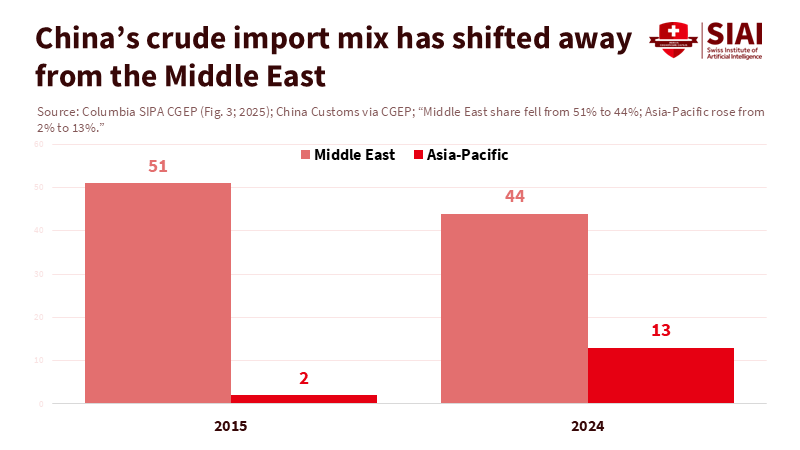

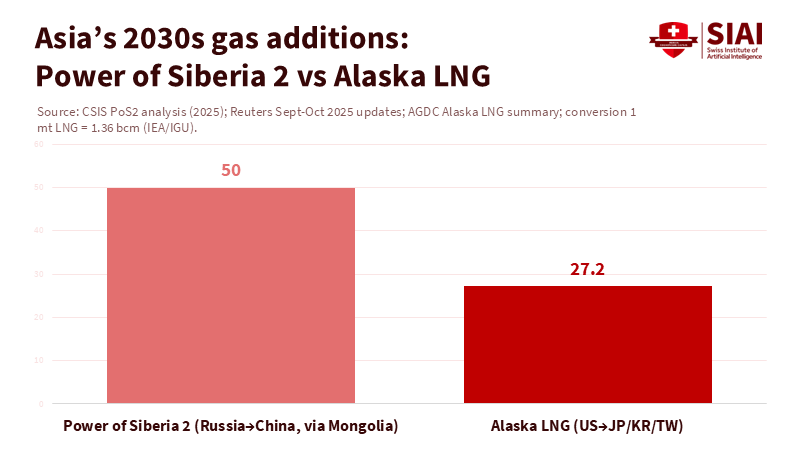

China's new energy situation can be summarized with one number: 50 billion cubic meters a year. That is the planned capacity of Power of Siberia 2, a pipeline that, if built as intended, would transport about 0.9 million barrels of oil per day from Russia to China. When combined with the 20 mtpa Alaska LNG project, which is currently seeking Japanese, Korean, and Taiwanese buyers, Asia could see around 77 bcm of additional gas by the early 2030s. This development comes as China's fuel demand appears to have peaked, and the share of crude imports from the Middle East has decreased from about 51% to 44%. The main story is not a sudden crash in oil prices. It is a shift in bargaining power: more reliable gas for China, a reduced geopolitical risk premium on oil, and tougher negotiations for every supplier—from OPEC's leading players to U.S. LNG advocates—especially if Power of Siberia 2 progresses on schedule.

Power of Siberia 2 and the end of one-way energy risk

For the past decade, China's instability has been framed around Middle Eastern oil, U.S. LNG, and key maritime chokepoints. That view is outdated. Beijing has diversified its suppliers, increased its reserves, and shifted towards pipeline gas, which is harder to sanction and cheaper to transport. Energy trade between China and the U.S. has shrunk to nearly zero, creating more fiscal space for Russia-China relations and promoting long-term gas hedging over volatile spot LNG. Power of Siberia 2 extends this hedge: a 2,600-km route through Mongolia that is designed for up to 50 bcm/year, building on the first Power of Siberia line, which is now nearing 38 bcm/year. In practical terms, this means China can secure a larger share of its winter heating and industrial fuel through contracts rather than scrambling on the spot market during price spikes. This shifts the regional focus from tanker routes to pipelines.

The strategic implications are not balanced. Russia needs this project more than China does, which is why discussions have been slow regarding price indexing, capital expenditure, and transit conditions. Moscow's urgency has increased as pipeline sales to Europe have plummeted, while Beijing's has not, thanks to growing gas options. In September, Gazprom and CNPC signed a legally binding agreement for Power of Siberia 2. They expanded existing routes, but pricing and financing remain unresolved. Reuters' timeline is cautious: even with a deal next year, initial deliveries could take about five years, and half-capacity may not be realized before 2034-35. This gradual ramp-up is the key policy insight. Power of Siberia 2 resets leverage immediately by altering expectations and contracting behavior, even if the gas arrives later.

How much oil would Power of Siberia 2 actually displace?

We must be clear: Power of Siberia 2 is a gas project. Gas competes with coal in power generation and with coal and oil in industries, freight, and heating. It does not replace gasoline in personal vehicles. The pipeline's 50 bcm translates to about 45 Mtoe per year, or roughly 0.9 mb/d oil-equivalent—a significant number that invites broad claims about oil. Yet oil accounts for only about 18% of China's primary energy, and demand growth is now driven by petrochemicals rather than fuels. The IEA states that oil demand in China has plateaued, with combined gasoline, diesel, and jet fuel consumption remaining at pre-pandemic levels. In 2024, China's crude imports even dropped by roughly 1.9% compared to the previous year. These trends indicate why Power of Siberia 2 will primarily pressure LNG prices first and oil risk premiums second, rather than causing a direct crash in Brent prices.

The impact on oil is indirect. The share of China's crude imports from the Middle East has dropped from about 51% to 44%, as increased flows from Russia and Asia-Pacific sources offset the decline. This reduces the geopolitical premium associated with Gulf disruptions, as it becomes more difficult to pressure China. At the same time, Beijing's quick rollout of electric vehicles and LNG trucks in heavy freight is taking a toll on diesel and gasoline. Analysts now estimate that China's EV fleet is already displacing around 1 mb/d of inferred oil consumption, while LNG trucks are capturing a significant share of heavy-duty sales. In this context, Power of Siberia 2 is another factor that pushes oil down the priority list: gas replaces oil at the margins in specific industrial and transport sectors and, importantly, allows China to purchase oil as an option, rather than being held hostage to price increases.

Pricing, sanctions, and the Alaska LNG counterweight

The main points of contention between Moscow and Beijing focus on who will pay for the pipeline and transit costs, how prices will be indexed, and how long-term market risk will be shared. Carnegie's analysis of pricing is relevant here: Russia's breakeven point is near $125 per 1,000 m³, while LNG alternatives have averaged around $370 per 1,000 m³, allowing room for negotiation until risks from sanctions and financing costs are factored in. This is where U.S. policy comes into play. In March 2025, Donald Trump threatened significant tariffs on buyers of Russian oil. Then he linked participation in Alaska LNG to tariff relief for Japan, Korea, and Taiwan—an approach designed to limit Russian volumes in Asia's future demand. Letters of intent soon followed, with JERA, POSCO, and Tokyo Gas expressing interest in offtake as Glenfarne seeks financing. The Alaska project aims for ~20 mtpa with a startup date of around 2030-31, pending final investment decisions.

If both Power of Siberia 2 and Alaska LNG proceed, Asia's gas landscape in the 2030s will look very different. The IEA predicts a surge in global LNG supply through 2030, while China's LNG requirements declined by 17% year-on-year in the first three quarters of 2025 as piped volumes from Russia increased and domestic production rose. This combination reduces Asia's vulnerability to winter price spikes, which previously drove oil substitution in 2022. It also strengthens buyers' bargaining power in contract negotiations. In September, Russia indicated a desire for closer pipeline ties to China. Yet, reports from Reuters, OIES, and others anticipate a slow ramp-up for Power of Siberia 2 and considerable uncertainty regarding pricing formulas. In short, expect a prolonged pricing negotiation influenced as much by sanctions dynamics and financing politics as by engineering.

What should universities and ministries do now?

Educational institutions and government agencies need to keep pace with the market design landscape, not just the raw materials story. Curricula in economics, energy systems, and international relations should cover contract structures, pricing mechanisms, and sanctions-related risks, in addition to pipelines and reserves. Students should understand how an oil-indexed gas contract can adversely impact a utility, how secondary sanctions affect bank compliance, and why the Mongolia transit segment alters bargaining dynamics. This requires practical, case-based learning focused on the Power of Siberia 2 negotiations and the Alaska LNG commercial model. It must also involve reviewing datasets from the IEA and the Energy Institute to measure how gas and oil interact in real-world demand situations, rather than assuming one replaces the other. The next generation of energy leaders will need to craft procurement agreements and establish national stockpiling regulations, not just write theory papers.

Administrators and policymakers should conduct scenario drills to test procurement and public finance risks across three possible outcomes: Power of Siberia 2 delayed, on time, and alongside Alaska LNG. In parallel, ministries should assess the potential for oil-to-gas switching in industry and heavy transport, and eliminate remaining regulatory obstacles to gas distribution where it can replace oil. Most importantly, they should prepare budgets for transition risks associated with long-term gas infrastructure: potential stranded assets if demand declines more quickly, counterparty risks if sanctions expand, and vulnerabilities to pricing formulas that can fail in a tight market. The data points to cautious optimism: China's fuel demand is plateauing, global LNG supply is increasing, and pipeline gas to China is picking up. However, optimism alone is not a policy. The correct response is to build the capabilities of individuals who can navigate contracts as skillfully as they would a map.

The argument for a structural reset is strong. Power of Siberia 2 promises 50 bcm of firm gas to China. Alaska LNG contributes an additional 20 mtpa to the same area. China's fuel demand seems to have peaked, and its reliance on Middle Eastern crude imports is dwindling. None of this ensures a drop in oil prices. Instead, it does something subtler and more sustainable: it reduces the risk premium stemming from overdependence on tankers and contested maritime routes, and shifts power to large Asian buyers, who can now leverage pipeline, LNG, and storage against one another. The policy challenge is to develop institutions and educational programs that can assess these risks in real time, negotiate contracts effectively, and avoid being cornered by any single supplier. If we achieve this, Asia's energy costs in the 2030s will be lower and more stable—not because oil has disappeared, but because Power of Siberia 2 and similar projects have changed the rules of the game.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Carnegie Politika. (2025, Sep. 22). Why Can't Russia and China Agree on the Power of Siberia-2?

Columbia SIPA CGEP. (2025). China's Oil Demand, Imports and Supply Security.

CSIS. (2025, Sep. 5). How the Power of Siberia 2 Deal Could Reshape Global Energy.

East Asia Forum. (2025, Oct. 31). Power of Siberia 2 reshapes China's energy security calculus.

Energy Institute. (2024). Statistical Review of World Energy 2024.

IEA. (2025, Oct.). Gas 2025—Medium-term market report (and Executive Summary, datasets).

IEA. (2025). Global Energy Review 2025—Natural Gas.

IEA. (2025, Mar. 11). Oil demand for fuels in China has reached a plateau.

IEEJ. (2025, Sep. 2). The New Pipeline Agreement Between Russia and China.

IEEJ. (2025, Oct. 10). Now and the Future for Alaska LNG Project.

OIES. (2025, Sep. 1). China–Russia: the gas hedge (Comment).

Reuters. (2024, Dec. 2). China completes full pipeline for Power-of-Siberia gas; 38 bcm in 2025.

Reuters. (2025, Jan. 13). China's crude oil imports fall in 2024, first time in two decades outside COVID.

Reuters. (2025, May 21). Sinopec sees China gas demand peaking near 620 bcm between 2035–2040.

Reuters. (2025, May 22). U.S. invites Asian officials to Alaska; eyes $44 bn LNG project.

Reuters. (2025, Sep. 2). Gazprom, CNPC sign agreement to increase gas supplies; PoS2 memorandum.

Reuters. (2025, Oct. 7). Russia's pipeline deal with China seen taking a decade to boost exports.

Reuters. (2025, Sep. 10). Japan's JERA inks LNG offtake from Alaska's $44 bn export project.

S&P Global Commodity Insights. (2025, Apr. 9). Major Alaska energy deal could narrow U.S. trade deficit.

The Guardian. (2025, Mar. 30). Trump threatens tariffs on buyers of Russian oil.

Comment