Tax Exodus and the Informal Economy: How High-Tax Fixes Can Shrink the Base

Input

Modified

Informality and “tax exodus” rise when governments hike taxes in downturns UK and France show wealth flight Predictable, narrow rules keep money formal

One key fact should guide every budget meeting this winter. In certain parts of Europe, about one euro in three is earned off the books. This is the average size of the informal economy in Southern Europe from 1999 to 2020, and it continues to change. When governments raise taxes during downturns, informality increases and becomes entrenched. Tax hikes can lead to exits from the formal system that are difficult to reverse, even after growth returns. This is the troubling aspect of today’s tax exodus, the legal counterpart to informality, now seen in wealthy countries. France is attempting to address a deficit projected at around 5.4% of GDP in 2025, with debt near 116% of GDP.

Meanwhile, the UK is considering an exit tax for wealthy emigrants. Simultaneously, Dubai’s prime property values have risen sharply over the last five years, and British buyers have increased their presence. The trend is clear: when high-tax solutions meet low-trust environments, money and activity seek an exit. Governments can slow this trend, but they need to differentiate aggressive headline tax policies from sustainable tax strategies.

From Informality to Tax Exodus

In tough times, the instinct is to rely on the formal sector. This reaction is understandable, yet it misinterprets how behavior changes when tax signals meet risk and distrust. Research indicates that informality is counter-cyclical and highly responsive to fiscal tightening. When governments raise rates or broaden tax bases during periods of weak growth, some businesses and earners move into the shadows and remain there, leading to lower future tax returns. The outcome is a smaller and more fragile tax base, even after the crisis ends. While the underground economy is less prominent in advanced economies than in emerging markets, the underlying mechanism remains the same: if legal compliance feels punitive or unpredictable, individuals will navigate away from the formal system. Today’s tax exodus is the international version of this behavior. France is discussing changes to its wealth tax to address its budget; the UK is considering a 20% exit tax on unrealized gains for wealthy residents leaving. Both proposals aim for immediate revenue and fairness. Both could hasten the decision to relocate activities or residency before the rules become solidified. The experience from the UK’s non-dom regime is telling: despite a decrease in numbers for 2023-24, total revenue from current and former non-doms still reached about £12.5 billion, highlighting how heavily reliant revenue is on a small, mobile group. Push too hard, and you not only alter tax bills; you also change tax bases.

The geography of the tax exodus can be observed in asset markets. Dubai’s prime property values have surged since 2020, driven by rising demand from the UK. Brokers report that UK buyers have become the leading foreign group, with British investment in Dubai homes increasing by over 60% year-on-year in the second quarter of 2025, as developers have even established London sales offices. Real estate data can be inconsistent and promotional; however, the overall direction matches policy updates in London and Paris. When high-income taxpayers question the stability of domestic rules—concerning inheritance, capital gains, and exits—they take precautions by changing where they live and where they hold assets. This is entirely legal. The fiscal impact at home is similar to that of informality: the taxable base shrinks, enforcement becomes more challenging, and each subsequent tax increase yields less than the previous one.

Why High-Tax Fixes Shrink the Base

The instinct to “tax where the money is” can backfire when both money and activity are easily movable. Across the OECD, the tax burden on an average single worker reached 34.9% of labor costs in 2024, the highest level since 2017, driven by broad, incremental tightening after the pandemic. However, labor tax burdens only tell part of the story. What matters for base erosion is not the headline tax rate but credibility, predictability, and perceived fairness in the system. France’s fiscal outlook illustrates this tension: staff projections indicate the deficit will narrow this year but remain high without additional measures, and debt levels will rise if consolidation falters. In such situations, new taxes or revivals of wealth taxes suggest that more is on the way, even if the initial impact is minimal. Behavior shifts in response to signals, not merely to laws.

The UK’s tax discussions offer another lesson. HMRC’s latest statistics show that the number of non-dom taxpayers has declined slightly from pre-pandemic levels. At the same time, tax revenue from this group has increased. The Office for Budget Responsibility’s costing documents and independent analyses stress that the revenue from changes to non-dom rules hinges significantly on how many high contributors depart, the speed of their departure, and the structure of their investments. This responsiveness is considerable, even with a minor change in numbers, since a small group pays a large portion of the tax bill. A poorly thought-out tax exodus charge can reinforce the idea that it’s wiser to leave now, rather than later. Given that many G7 nations already have exit or departure taxes—France on significant shareholdings, the United States on certain expatriates, and Germany on extensive holdings—UK policy must align with international practices while avoiding punitive, retroactive elements that could lead to legal disputes and harm its reputation.

There’s an additional complication. Lowering tax rates alone usually does not significantly reduce informality; businesses and workers respond to the quality of enforcement, ease of administration, and perceived fairness of services as much as to the tax rate itself. Therefore, an approach focused solely on incentives—paying individuals to stay in the formal system—can be both costly and ineffective if compliance is poor and services fall short. Similarly, a strict crackdown can increase costs and push borderline actors underground. The most effective solution is a combination of reliable rules that are difficult to manipulate, straightforward systems for small businesses, and transparent, fair, and prompt enforcement.

What Holds People in the System

The right question for near-distressed states is not, “How much more can we collect this year?” but rather, “What keeps the marginal euro within the formal system next year?” Three key factors matter. First, stability is more important than generosity. OECD data show that many countries increased tax burdens in 2024. If revenue must be raised, do so with temporary measures that are clearly defined and automatically scheduled to end, accompanied by a clear plan detailing when and how the additional charge will be removed. Permanent taxes are a way to lose tomorrow’s base for today’s income. The plan must be detailed enough for investors to assess and for courts to evaluate.

Second, design with mobility in mind. An exit tax can be justified if it aligns with international standards: focus on unrealized domestic gains in significant holdings; allow deferrals and bonding, particularly within the EU/EEA; and credit foreign taxes to reduce double taxation. France already implements this with automatic deferrals within the EU and on-demand deferrals beyond it; Germany charges a notional tax on gains for residents leaving with substantial shareholdings. If the UK moves forward, it should adopt these protections, not just the main tax rate. Construct the system as a specific integrity rule, not a general anti-emigration penalty.

Third, reduce the costs of being formal. Research from the IMF on turnover taxes indicates that simple, low-rate systems for micro-enterprises—around 2-3% of sales—can engage small participants without the burdens of profit tax accounting. The idea is not that a 2.5% turnover tax is perfect everywhere; instead, friction and fear—not just price—influence compliance. When these systems are paired with visible service improvements, such as quick licensing, digital invoicing, and vendor financing from public banks, informality decreases more significantly than with simple tax rate adjustments alone.

The Policy Test: Revenue Now, Formality Later

What actions should ministers take in countries facing difficulties? Start by replacing flashy symbols with lasting solutions. If a wealth tax is necessary in France to meet EU fiscal requirements, limit it to specific, less mobile asset types and include an expiration clause in the law. Pair it with genuine spending limits, as IMF staff suggest, because attempting to bridge a structural gap with mobile capital will likely lead to disappointment. If the UK implements a tax exodus fee, keep the scope narrow, provide detailed guidance before it takes effect, and offer a grace period for transferring assets into clearly taxed vehicles. The objective is to minimize opportunities for manipulation and reduce uncertainty, not merely to grab headlines.

Next, focus on areas where behavior is most responsive. In labor markets, tax burdens on average workers increased throughout much of the OECD in 2024. Avoid further pressure there if you can boost revenue by improving compliance in capital and corporate taxes. Strengthen ownership registries and information sharing; invest in audits that analyze payment data; and publish enforcement statistics every quarter to reset expectations. The message must communicate that formal activity is easier and safer than alternatives, both local and overseas. This is how to slow the movement into the shadows and the rush to leave.

Finally, monitor the asset markets that reflect this situation. British home purchases in Dubai surged after a major tax announcement. At the same time, luxury transactions in France stalled amid discussions of a wealth tax. These are significant signals. They indicate whether the tax base will grow or shrink in the coming months. The trends offer feedback; ignoring them transforms a temporary fix into a long-lasting issue.

The informal economy is not a moral failure; it serves as a macroeconomic signal. When governments in wealthy countries resort to blunt, obvious tax solutions in weak economies, they provoke two forms of pushback: the traditional escape into invisibility and the modern tax exodus across borders. Both reduce the tax base, become more entrenched over time, and worsen debt situations. The choice isn’t between fairness and growth; it’s about selecting between superficial measures that pursue a dwindling tax base and less glamorous reforms that keep the base from diminishing. The route forward is straightforward. Use temporary, time-limited surcharges as needed. Align any exit charges with international practices and safeguards. Make formal participation more affordable and linked to tangible service benefits. Accept that credibility serves as a revenue tool. Suppose we create rules that people can depend on. In that case, the marginal euro will remain in the light, and the subsequent downturn won’t push a third of the economy back into the shadows.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Financial Times. (2025, Aug.). Non-dom tax take jumped £100mn in 2023–24 despite falling numbers.

France24. (2025, Oct. 31). French parliament debates duelling proposals to tax the wealthy.

The Guardian (Rawlinson, K.). (2025, Nov. 1). Rachel Reeves considers 20% tax on assets of people deciding to leave UK.

HM Revenue & Customs. (2025, Jul. 17). Statistical commentary on non-domiciled taxpayers in the UK.

International Monetary Fund. (2023). Designing a Presumptive Income Tax Based on Turnover (WP/23/267).

International Monetary Fund. (2025). France: 2025 Article IV Consultation—Staff Report (Country Report No. 25/179).

Knight Frank. (2025). Why the success of Dubai’s property market looks set to continue in 2025.

OECD. (2025). Taxing Wages 2025: Effective tax rates on labour income in 2024.

Office for Budget Responsibility. (2025, Jan. 30). Costing of reforms to the non-domecile regime (Supplementary release).

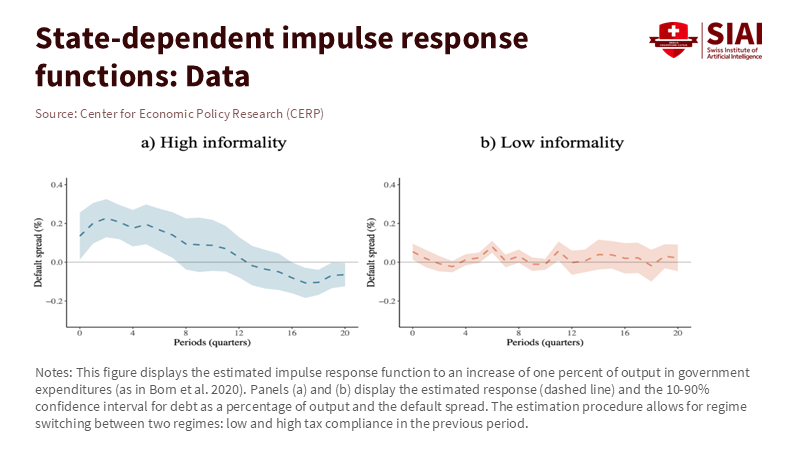

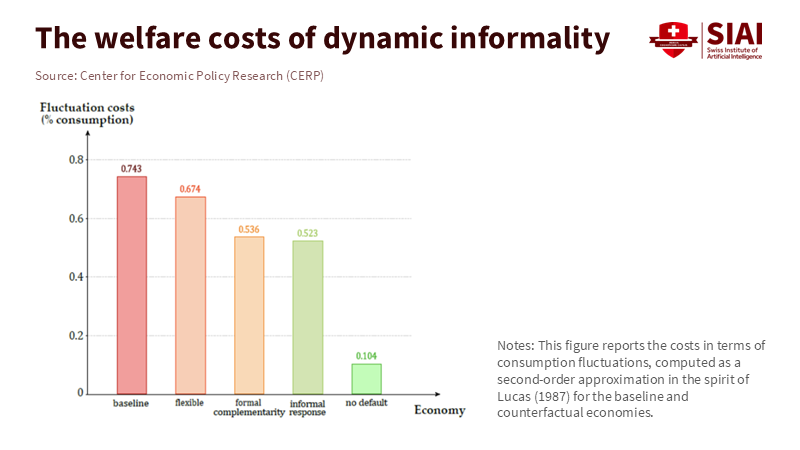

Pappadà, F., & Zylberberg, Y. (2025, Nov. 1). The hidden cycle: How informality shapes fiscal policy and sovereign default. VoxEU/CEPR.

Reuters. (2025, Oct. 31). French lawmakers weigh wealth-tax options to fix budget hole.

Reuters. (2025, Sept. 7). Dubai looks to capitalise on weak dirham to lure British home buyers.

The Independent (Devlin, K.). (2025, Nov. 1). ‘Settling-up charge’ being considered for wealthy leaving UK.

UK Government. (n.d.). Taxing Wages 2025: The United Kingdom (country note). OECD.

Comment