European Debt Guilt and the Hard Math of Public Choices

Input

Modified

European debt guilt is deep-rooted and won’t be reversed by information campaigns Rising interest costs, defence needs, and ageing populations are crowding out core services Be honest: set real plans and rank priorities

As we delve into the intricate web of European fiscal policy, it's crucial to understand the urgency of our situation. The hard truth is that we're facing a budgetary squeeze, and it's time to make some tough decisions. The facts are stark: in 2024, government interest payments in OECD countries soared to 3.3% of national income, the highest share since 2007. This figure surpassed combined spending on defense, policing, and housing, marking a significant shift in fiscal priorities. It's a clear indicator of the trouble we're in. Interest rates are higher, the post-pandemic debt is substantial, and refinancing is constant. With Europe’s significant defense buildup and rising aging costs, there is little room left. Amid this, European debt guilt—the belief that debt is something shameful—does not simply disappear with public information campaigns. It strengthens. Voters remember the cuts, not the exceptions. They notice bills arriving faster than services improve. Our task is not to “teach people to love debt,” but to be honest about the numbers and the choices they require.

The Limits of “Education”: Why European Debt Guilt Runs Deep

A 2025 study, conducted across multiple European countries, found that using the guilt-laden term for “debt” in Germanic languages lowers support for public borrowing and decreases genuine willingness to borrow, even when it makes financial sense. Context is important—people are more open when the purpose is clear—but the base effect is evident: words and moral frames stick. European debt guilt is not just a way of speaking; it shows up in behavior. This reality makes it a poor candidate for quick fixes through messaging campaigns.

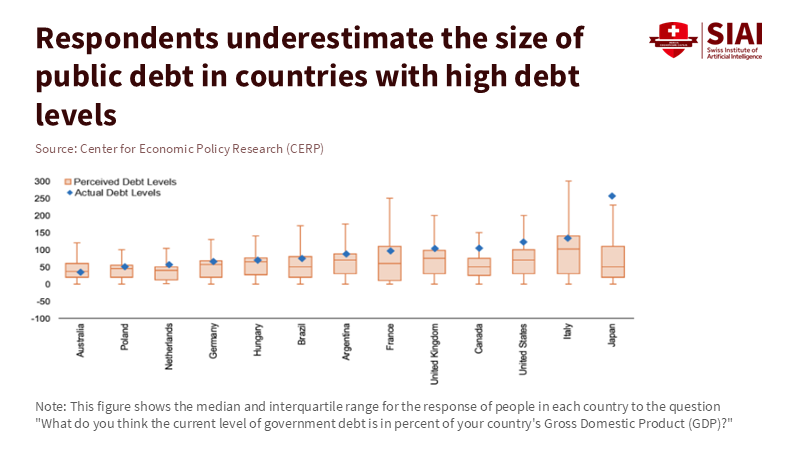

A second 2025 study across multiple countries challenged the optimism that “more information” would change views. When people in 13 countries received better facts about debt, their expectations shifted slightly and were influenced by past experiences. Those who had lived through cuts expected more losses; their trust diminished when spending decreased. Information helped some groups, in some places, but it did not erase the core belief that public debt creates future losers—and that “loser” might be them. This is European debt guilt in action: a mix of memory and risk aversion, not a misunderstanding that a simple leaflet can resolve.

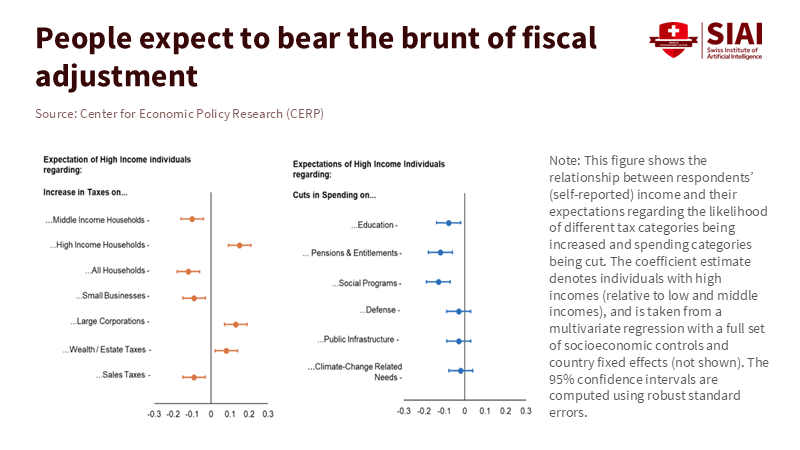

If we want public support for realistic budgets, we need to start where voters actually are. Many people underestimate overall debt while overestimating the personal costs they will face from adjustments. They hold on to past shocks. They find moral significance in fiscal language. This captures the political landscape accurately. Assuming that a new explainer video will change deep-seated beliefs does not reflect reality.

The Squeeze Is Real: Interest, Defense, and Aging Crowd the Budget

The fiscal squeeze is clear; it’s reflected in budget items. Interest costs are rising as cheap pandemic-era debt matures. On average across OECD countries, the share of GDP devoted to interest payments increased in 2024. It will likely remain high as debts mature. This creates a non-negotiable claim on revenue before funding any classrooms, clinics, or rail cars.

Defense is a second source of pressure, and it is increasing. NATO reported a record jump in allied spending since 2014; by 2024, 23 allies had met or exceeded the 2% of GDP goal. Europe’s total military spending rose 17% in 2024 to $693 billion, the highest since the Cold War ended. The European Commission’s spring forecast notes that defense spending is growing as a share of economic activity, especially near Russia’s borders. Suppose the United States reduces its role in Europe. In that case, the financing issue becomes more serious: the International Institute for Strategic Studies estimates that around $1 trillion would be needed over time to replace US conventional capabilities, along with personnel, leadership roles, and the intelligence backbone currently provided by Washington. This is more than just a messaging issue. It is a budget reality.

Aging is the third factor. Europe’s most significant government function is social protection. In 2023, social benefits accounted for about 26.8% of EU GDP, and social protection accounted for roughly 39% of total government spending. Pensions alone consume about 12% of GDP on average. Even if nominal spending levels off, demographic changes raise the baseline. The space for new priorities—like defense, climate adaptation, and productivity-boosting investments—shrinks. European debt guilt intensifies when citizens see interest payments and defense spending take precedence over the local services they rely on daily.

Honesty Over Persuasion: What Transparent Budgets Should Look Like

When it comes to budgeting, transparency is key. If we acknowledge that attitudes change slowly, the right policy approach is transparency, not reframing. Start by publishing credible, multi-year primary balance projections that reflect realistic interest rates and growth potential, rather than optimistic averages. Demonstrate how net spending rules translate into department-level limits. Pair every spending plan with an honest explanation of its impacts by income and demographic group. Do not promise that “no one will pay”; discuss the trade-offs. This is how we build fiscal trust.

Next, test budgets against defense scenarios that security experts consider likely. A sensible baseline would maintain current NATO spending, given that Europe may need to take on a larger share of the alliance’s defense burden. This means the budget should be prepared for a scenario in which Europe is responsible for a significant share of the alliance's defense spending. Use the IISS replacement estimate to guide equipment and workforce requirements, then calculate the logistics, munitions, and industrial capacity needed for support. Put those numbers alongside health, education, and pensions in one table. Citizens can handle the arithmetic; they dislike marketing tactics.

Third, protect vulnerable groups with automatic stabilizers while revising universal subsidy policies. Set triggers to maintain means-tested support if unemployment rises or food and energy prices spike, but phase out broad rebates that drain fiscal resources. The aim is not punishment but a sensible sequence. In a high-interest environment, every euro spent without a clear growth or resilience benefit increases tomorrow’s taxes or reduces future services. European debt guilt will only ease when voters see a steady, rules-based approach that protects essentials, meets promises, and recognizes limits.

What to Cut, What to Keep: A New Spending Order

Europe requires a revised spending hierarchy—one that prioritizes funding based on its potential to enhance long-term capacity, rather than who shouts the loudest. First, focus on investment with proven growth benefits, such as early childhood education, targeted skills training, and maintenance that prevents expensive failures. Second, prioritize defense capabilities and stocks that quickly address alliance shortages. Third, implement pension and health reforms that reduce costs without breaking commitments—such as raising retirement ages in line with life expectancy, consistently means-testing universal benefits, and reforming procurement to cut waste in hospital and drug spending. This is not about austerity for its own sake; it is triage in a high-interest world.

On the revenue side, do not assume that growth will automatically “pay for itself.” The Commission has already proposed new sources of funding to stabilize the EU budget. Member states will need efficient tax reforms: fewer loopholes, fewer special rates, and transparent bases that are hard to exploit. Small tax increases that affect the same salaried middle class are politically unstable and contribute to the skepticism represented by European debt guilt. Broadening the tax base and eliminating low-value exemptions is more effective than flashy surcharges that yield less than promised.

Finally, governments should publish a dashboard each budgeting season showing interest-to-revenue, defense-to-GDP, pension-to-GDP, and the share of “freely programmable” spending left after fulfilling entitlements and debt obligations. In Germany, analysts warn that disposable income may decline sharply without reform as debt payments and age-related costs rise. Becoming comparable across capitals would spark a necessary conversation: what gets cut when everything is protected?

Choose Honesty Over Campaigns

Interest costs at 3.3% of GDP, now larger than the combined budgets of several key public safety functions. This is not a failure of communication. It is the budget reflecting a decade of easy money and a rapid shift in Europe’s security landscape. It also explains why European debt guilt won’t fade with better brochures. People are facing a real financial squeeze: rising interest payments, increasing defense expenses, and aging systems that promise more than their contributions can support.

The way forward is not to convince citizens to love debt. We must first be honest: show the multi-year figures, acknowledge limits, prioritize what matters, and pair every new promise with a specific way to pay for it. This approach may not dominate news cycles, but it can restore credibility, which is the rarest fiscal resource Europe has. When voters see leaders protecting essentials, funding deterrence, and ceasing to act as if everything can be shielded at once, they will accept difficult trade-offs—even if their feelings about the term “debt” remain unchanged. A political approach that treats people as adults has a better chance of lasting than one that views them merely as targets for persuasion. In a high-interest world, honesty is not only the ethical choice; it is the only sustainable one.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Aksoy, C. G., Dolls, M., Klejdysz, J., Peichl, A., & Windsteiger, L. (2025). Speaking of debt: Framing, guilt, and economic choices. VoxEU/CEPR, 23 Oct 2025.

Bianchi, F., Dabla-Norris, E., & Khalid, S. (2025). When debt perceptions shape fiscal futures. VoxEU/CEPR, 2 Nov 2025.

ECB. (2025). Interest payable (Government finance), Euro area data portal (updated July–Oct 2025).

European Commission. (2025a). Spring 2025 Economic Forecast: Moderate growth amid uncertainty (Executive Summary).

European Commission. (2025b). The economic impact of higher defence spending (Spring 2025).

European Fiscal Board. (2025). Annual Report 2025.

Eurostat. (2024–2025a). Social protection statistics—early estimates (2023).

Eurostat. (2025b). Government expenditure on social protection (COFOG).

IMF. (2025). World Economic Outlook, October 2025.

IISS. (2025). Defending Europe Without the United States: Costs and Consequences. Research Paper, May 2025.

NATO. (2024). Defence expenditure of NATO countries (2014–2024), press materials and data.

NATO/CRS. (2024). NATO’s Washington Summit: In Brief (showing 23 allies at/above 2% in 2024).

OECD. (2025a). Global Debt Report 2025 (and press release).

Reuters. (2024–2025). Allies meeting 2% target; Rutte on potential 3.7% need.

SIPRI. (2025). Trends in world military expenditure, 2024 (Fact Sheet).

Comment