Gene Editing Access at a Crossroads: From Breakthroughs to a Public Playbook

Input

Modified

CRISPR cures are real, but access is narrow High costs, fragile care pathways, and shaky investment block scale Share risk on payment, build training and data networks, and enforce anti-eugenics rules to make gene editing access a public good

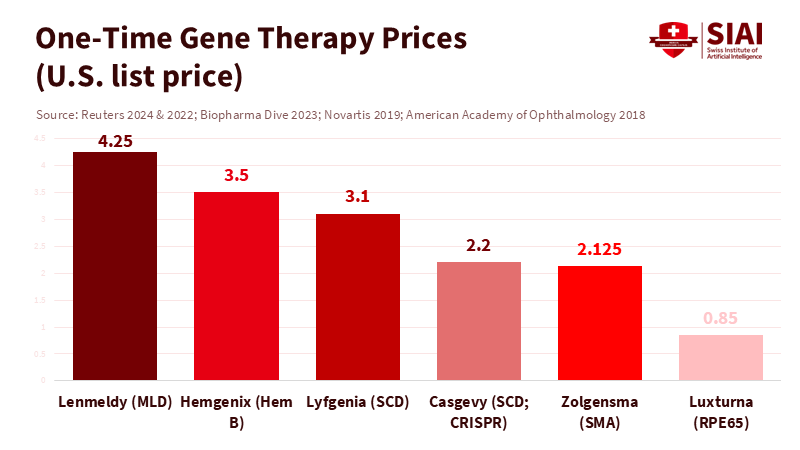

Ninety-five percent of rare diseases still lack effective treatment. This fact highlights both the potential and the challenges of access to gene editing. While a few one-time therapies are available, their costs range from about $2.2 million to $3.5 million per patient. These therapies can change lives, but they have not yet transformed the healthcare system. The first CRISPR-based gene-editing therapy has received regulatory approval, with more on the way. However, the field is shifting from demonstrating concepts to a challenging reality: securing funding, hiring staff, and navigating ethical issues to deliver services at scale. To ensure that precise cures reach classrooms, clinics, and communities—rather than just being showcased at conferences—we urgently need a public playbook that cuts costs, reduces risks, and avoids the possibility of eugenics. The central question has shifted from “Can we edit?” to “How do we create fair and sustainable gene editing access?”

The promise and the bottleneck in gene editing access

The scientific signal is clear. Regulators have approved the first CRISPR therapy for sickle cell disease, and other genetic treatments are in development. Clinical trials show real benefits for conditions that once meant a lifetime of suffering or a significantly shortened life. This marks a significant achievement for both science and patients. Still, these advances do not guarantee broad access to gene editing. Each indication represents a small market with its own biology and manufacturing processes. There is no single solution, which makes scaling difficult. Because each product targets a specific group, the per-patient costs remain high, and payers hesitate. This mirrors a familiar pattern in rare-disease care: significant breakthroughs that help a few while leaving many behind. Regulatory approval opened the door, but did not create a wider pathway.

Pathways to care remain complicated. Most ex vivo editing requires myeloablative conditioning, often using busulfan, to make space in the bone marrow before reinfusion. This leads to the need for specialized centers, weeks away from work or school, and creates real risks such as infections and liver complications. Manufacturing must align with apheresis appointments, hospital beds, and pharmacy capacity. If a vial is delayed, conditioning cannot begin. These are not abstract issues; they are everyday operational challenges. They push access to gene editing toward a small number of academic hospitals and away from the locations where many patients live. No matter how sophisticated the editing, the system will fail if the care model is fragile.

Investment obstacles add to the pressure. After record funding in 2020 and 2021, investment in cell and gene therapy dropped sharply in 2022 and 2023. Many companies scaled back their programs and workforce. There are signs of selective recovery, but overall funding has shifted to shorter-term investments. This trend slows infrastructure expansion and keeps capacity limited. When the market signals caution, payers and hospitals hesitate, leaving patients waiting with them. The outcome is clear: groundbreaking science, narrow margins, limited capacity, and uneven access to gene editing.

Gene editing access needs a different economics

High prices make headlines. Casgevy’s listed price in the U.S. is about $2.2 million, while a competing sickle-cell gene therapy costs about $3.1 million. Several earlier gene therapies had prices ranging from $2.1 million to $3.5 million. One-time cures can be cost-effective over the long term, but the initial cost can shock budgets. Insurance plans change members every year, meaning the payer who funds the cure may not benefit later. This turnover creates a classic public goods issue. Without new contracts, coverage will be slow and uneven. Access to gene editing will depend more on insurance design and employer size than on clinical effectiveness. This is not a scientific limitation but rather a policy choice.

There are practical solutions. Outcomes-based contracts tie payment to actual benefits over time, and annuity models spread costs over several years. Subscription models—sometimes referred to as the “Netflix model”—swap volume risk for access and have demonstrated their ability to facilitate treatment at scale in hepatitis C programs. In Louisiana, prescription fills increased more than fivefold under a subscription deal. A 2025 analysis indicates broader improvements with intentional implementation. These approaches do not resolve every uncertainty, but they create better incentives today. Payers typically want at least five years of reliable benefits to justify costs; therefore, contracts should reflect this. For gene editing access, the immediate goal is not to have perfect evidence but to share reasonable risks so patients do not find themselves without coverage while data develops.

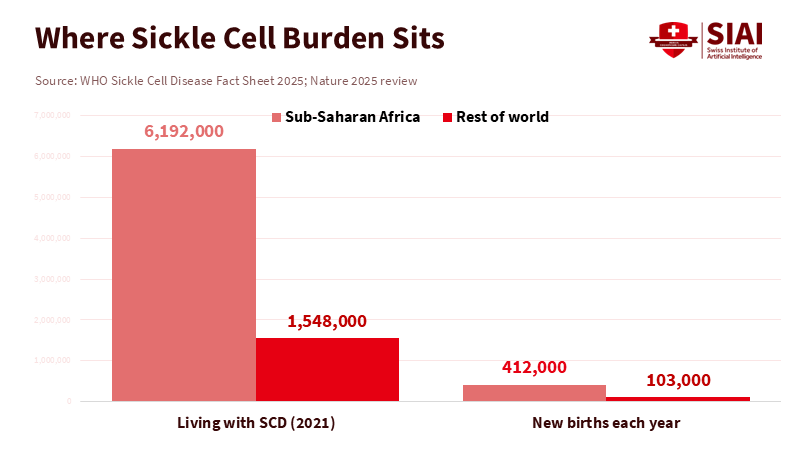

Global equity raises a more challenging issue. Sickle cell disease is most prevalent in areas where health systems are least equipped. About 80% of people with this condition live in sub-Saharan Africa, with hundreds of thousands of babies born with it each year. A $2–3 million autologous therapy requiring transplant-level infrastructure will not be available to them anytime soon. Suppose we aim for access to gene editing. In that case, we need tiered pricing, technology transfer, and public manufacturing of essential components, such as vectors and reagents. We need simpler in vivo methods that bypass conditioning and reduce hospital stays. Funders must also recognize equity as a central performance metric rather than just a corporate social responsibility aspect.

Guardrails for gene editing access, not a Gattaca slide

Therapy and enhancement are not the same thing. The international consensus since 2023 is clear: heritable human genome editing is unacceptable. The science is not ready, and the governance is not established. Somatic editing to treat disease is advancing, and it should continue to do so. However, access must expand within strict guidelines to prevent the creation of markets that favor wealth over necessity. The quickest way to invite a “Gattaca” future is to underfund therapeutic programs while letting enhancement services dictate the standard. The best way to avoid this is to craft policies that prioritize patients who stand to benefit the most and can pay the least. Access to gene editing can uphold that priority if regulators and payers work in unison.

These guidelines exist on paper. The World Health Organization’s governance framework establishes a baseline for oversight of somatic, germline, and heritable editing. National laws and professional standards provide additional layers of protection. However, rules on paper are only as effective as their funding and enforcement. As prices fall and technology improves, pressure will increase to offer edits for traits beyond disease. This is where access and ethics intersect. By creating transparent registries, clear clinical guidelines, and independent review processes, gene editing access can expand without sliding into eugenics. Failing to do so will allow market forces to fill the gap.

A public roadmap for gene editing access

Educators hold the first key. Genomic literacy should not be optional. Healthcare programs and teacher-training colleges can include modules on inheritance, risk, and the nature of edited therapies. Students should understand what an apheresis unit is, why myeloablation matters, and what informed consent entails for adolescents. Nursing and public health schools can incorporate micro-credentials in cell and gene therapy operations. Another pressing need is genetic counseling. The world currently has just over 10,000 genetic counselors across more than 45 countries. That marks progress, but demand is growing faster than supply. Degree programs can expand enrollment and establish remote counseling rotations at regional hospitals, thereby bridging access gaps to gene editing.

Administrators can build a strong foundation. Regional networks of certified centers can share clean-room time, staff, and data. Hospital groups can create shared apheresis schedules and on-call pharmacy teams so that conditioning and infusion occur on time. Data registries should track outcomes for years—not just months—to support value-based contracts. Newborn screening can serve as a multiplier, as early diagnosis enhances eligibility and outcomes. England’s Generation Study is sequencing 100,000 babies to assess the real-world value at scale. With consent and privacy protections, this model can inform broader outreach and determine which edits should be included in national benefit packages. Administrators should view data management as a clinical asset rather than just a compliance obligation. That is how access to gene editing becomes part of standard care.

Policy is where the bottleneck can be resolved. Governments can test subscription models for specific gene-therapy groups, beginning with conditions that incur high lifetime costs. Health-technology assessors can publish “reference contracts” that combine outcome tracking with staggered payments. Tax regulations can allow payers to distribute one-time cure costs over several years, aligning cash flow with benefits. Regulators can expedite manufacturing changes that lower costs without sacrificing quality and support local vector production to mitigate supply risks. Public-private partnerships can back platforms for in vivo editing that eliminate the need for busulfan conditioning. Lastly, cross-border initiatives should standardize ethical guidelines to ensure that access to gene editing does not devolve into a competition over lax oversight. The main point is simple: we already possess many of the necessary tools; we need to integrate them effectively.

The primary statistic remains unchanged: more than nine out of ten rare diseases lack a proven treatment. That is why the discussion on gene editing access must shift from fascination to action. We have cures available; now we need a market and a public system to deliver them fairly. Prices will remain high unless we share risks. Capacity will remain limited unless we train more people and streamline the care process. Ethical standards will flounder unless we establish clear guidelines and fund them. Suppose we align payments with outcomes, expand genomic literacy, invest in centers and data, and maintain strict boundaries on heritable editing. In that case, we can broaden access without slipping into eugenics. The first generation of patients has demonstrated what is possible. The next generation will assess whether we built a system that lives up to the science—and whether access to gene editing became a public resource rather than a private privilege.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Alliance for Regenerative Medicine. (2024). Sector Snapshot: Review of the 2024 Cell and Gene Therapy Approvals.

Biopharma Dive. (2023, Dec. 8). Pricey new gene therapies for sickle cell pose access test (Casgevy $2.2M; competitor $3.1M).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). Data and Statistics on Sickle Cell Disease.

Genomics England. (2024–2025). Newborn Genomes Programme (Generation Study).

ICER & NEWDIGS. (2024). Managing the Challenges of Paying for Gene Therapy (white paper).

JAMA Health Forum. (2021). Medicaid Subscription-Based Payment Models and Access to Hepatitis C Medications (Louisiana experience).

Labiotech.eu. (2024, Nov. 11). Gene therapy investment struggles: What’s driving the slowdown?

National Bureau of Economic Research. (2025). Lessons from Louisiana’s effort to eliminate hepatitis C (Working Paper No. 33617).

Reuters. (2022, Nov. 22). CSL prices hemophilia B gene therapy at $3.5 million (Hemgenix).

Royal Society. (2023, Mar. 8). Statement from the Organising Committee of the Third International Summit on Human Genome Editing (“heritable … remains unacceptable”).

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2023, Dec. 8). FDA approves first gene therapies to treat patients with sickle cell disease (first U.S. CRISPR approval).

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2023). CASGEVY Package Insert (myeloablative conditioning guidance).

World Health Organization. (2021). Human genome editing: recommendations (governance framework).

World Health Organization. (2025). Rare diseases: draft resolution text (notes >95% of rare diseases lack effective treatment).

World Health Organization. (2025). Sickle-cell disease: Fact sheet (global burden and regional distribution).

Comment