Rebuilding the Center: Multicultural Education Policy for a Changing Australia

Input

Modified

Australia’s diversity is high; classrooms decide cohesion Data show immigrant students succeed with language support and safe schools Priorities: rapid language screening, teacher training, and clear cohort tracking

Australia is now one of the most migration-intensive democracies in the world. In 2023, 30.7% of residents were born overseas — about one in three people — the highest percentage since Federation. In schools, nearly a third of 15-year-olds come from immigrant backgrounds, one of the highest figures among OECD countries. However, net overseas migration, which reached a record 518,000 in 2022-23, is expected to decrease due to tighter rules and costs starting in 2024-25. These numbers tell a straightforward story, but it has a complicated background. The demographic shift will not reverse, even if visa pathways slow. Our institutions will shape the next decade. The critical question is not who belongs but whether our multicultural education policy can convert the country's diversity into stable, shared civic power during times of economic pressure and political noise.

Multicultural education policy as core state capacity

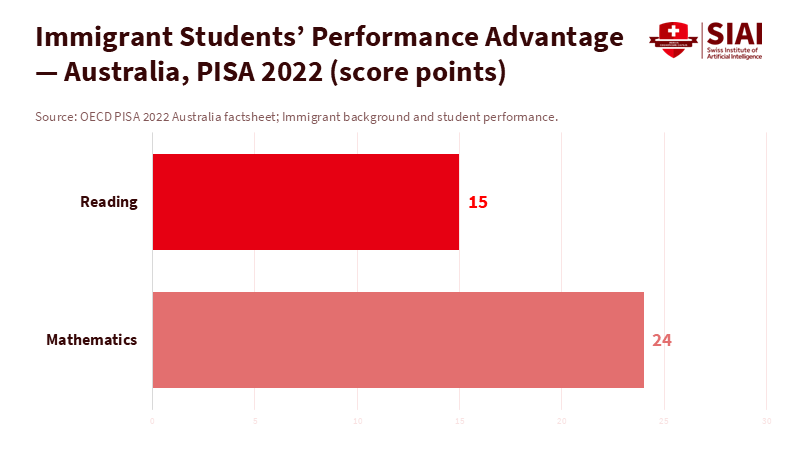

The old debate framed multiculturalism as a clash of cultures. The real challenge is institutional: can schools and universities quickly provide newcomers and established families with a common civic foundation? Australia has strong foundations. PISA 2022 shows that students with immigrant backgrounds perform at or above their non-immigrant peers when accounting for language and socioeconomic status. In simple terms, when schools recognize and support students early, their origins become less important in predicting success. This result is rare and valuable among OECD countries, but also fragile. Trends in classroom climate and bullying are not improving, which erodes trust for everyone involved. Multicultural education policy is not just an add-on; it is crucial in a world where demographics and geopolitics are shifting.

Australia also faces long-term aging. Treasury’s Intergenerational Report is clear: younger migrants help balance population aging and strengthen the workforce. We will continue to need them, even as the government tightens the student visa system to manage housing pressure and integrity issues. This policy choice comes with trade-offs. It makes what happens in classrooms even more crucial. If the intake is smaller and more selective, every year of lost learning for a newcomer becomes more costly. Every failure to support language skills and a sense of belonging hinders productivity, cohesion, and public confidence. Thus, a robust multicultural education policy is not just an educational issue; it is also an economic policy. It is as essential as housing supply and skills development for national resilience.

Europe’s parallel stress test and what classrooms can learn

Europe is experiencing a similar situation. On January 1, 2024, 44.7 million people born outside the EU lived in the region, just under 10% of the population, with higher percentages in several Western and Northern countries. Labor migration to wealthy nations fell in 2024 as rules became stricter, but numbers remain above pre-pandemic levels. The political debate is intense, while policy work requires patience. The EU’s Action Plan on Integration and Inclusion emphasizes early access to education, teacher development, language support, and recognition of qualifications. The message is clear. When education systems create structured pathways for newcomers, social tensions decrease. When they fail to do so, divisions fill the gap. This is not just a "European problem" or an "Australian problem." It is an issue of institutional capacity, with classrooms at the center and multicultural education policy as a critical tool.

What can Australia learn from Europe's experience? First, the size and origin of populations matter less than the speed and effectiveness of integration services. Second, teacher shortages and inconsistent training can undermine good intentions. Third, feelings of belonging and safety are as important as test scores. These are not abstract ideas. They address a common concern among principals and parents: Will my child learn in a calm environment, feel acknowledged, and make progress? When the answer is yes, communities remain united amid change. When the answer is no, fear increases, and politics become divided. The EU's policy tools may not serve as a direct model for Canberra. Still, their approach—providing earlier support, improving data, and enhancing teacher development— is appropriate for any country that wants to transform diversity into collective benefits. This is the essence of multicultural education policy.

Measuring what matters in 2025

If we want to build trust, we need to track the right metrics. Begin with language proficiency. Proficiency by the end of a student’s second full school year predicts long-term success. Countries that assess early and provide targeted support can reduce achievement gaps. Recent cross-national research shows that participation in high-quality early childhood education can decrease immigrant-native gaps in later PISA scores by more than a whole school year. Practically, this means ensuring funded access and not long wait-lists, as well as qualified staff who can integrate language learning into play and early literacy. For Australia, where early childhood education is already a priority, this is a wise investment with clear benefits in equity and productivity. It should be central to multicultural education policy.

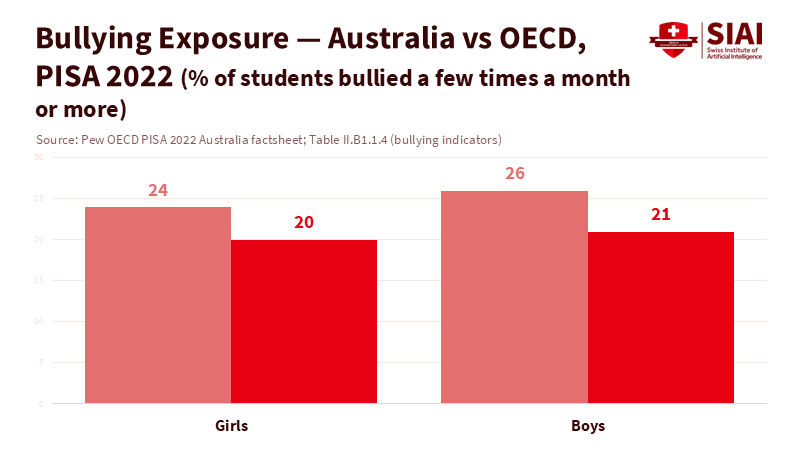

Next, track safety and feelings of belonging with the same seriousness as numeracy. PISA 2022 data for Australia reveal that bullying rates are above OECD averages, with about a quarter of students reporting victimization regularly. Bullying harms learning for all students, not just newcomers. It also creates resentment that politics can exploit. Schools should publish simple, comparable indicators at the school level, back evidence-based anti-bullying programs, and train staff to address digital bullying from social media. While there is no quick solution, schools can make progress by combining consistent rules with student input. A safer environment is the most cost-effective way to improve overall results and make multicultural education policy effective.

Finally, report achievement and progression by cohort instead of broad "background" categories. Australia often tells stories about groups; families experience schooling year by year. Transparent cohort dashboards that track language milestones, attendance, subject progression, and post-school pathways allow leaders to monitor real-time successes. They also contribute to more honest public discussions. When data show that immigrant-background students match or exceed their peers' performance, confidence increases. When gaps persist, the solutions become clear and specific: enhance early-years access, strengthen literacy support, or provide additional teacher coaching. This disciplined approach to measurement helps maintain the strength of our educational system as visa rules shift. It also safeguards the promise of multicultural education policy from the chaos of sensational headlines.

From culture wars to classroom design

Policy effectiveness hinges on design. The first design principle is speed. New arrivals should receive language assessments and a placement plan within two weeks. That plan must include intensive language instruction linked to mainstream classes, rather than years spent on a parallel track that hinders social interaction. The second principle is contact. Schools succeed when they create meaningful interactions through mixed-ability projects, peer tutoring, and extracurricular activities that bridge language and income divides. This approach embodies contact theory, which fosters dignity rather than mere compliance. The third principle is teacher capability. We cannot expect teachers to handle integration without the right tools. Funding for micro-credentials in second-language teaching, trauma-informed practices, and classroom management should be linked to career advancement. The OECD’s Education Policy Outlook emphasizes that, amid teacher shortages, boosting quality and capacity is essential.

Financing matters. The federal government has tightened international student visas and raised fees to address integrity and housing challenges. This decision affects university budgets and the support pipeline for EAL/D staffing in schools. Suppose we reduce the total number of students. In that case, we should reinvest part of those savings into integration efforts that support social agreement: early-years access, school-based language assistants, and community language initiatives. This is not a call for bigger government. It is a plea for smarter spending that recognizes where benefits multiply. In a financially tight decade, the most cost-effective approach to maintaining social cohesion is to fund the educational components that transform diversity into learning and belonging. This is a practical multicultural education policy.

Critiques deserve thoughtful responses. One argument is that rapid diversity harms learning and disrupts social order. Australia’s own results challenge this narrative. When we account for language and socioeconomic status, immigrant-background students perform as well as or better than their peers in PISA assessments. The actual barrier to learning is not the presence of newcomers but the lack of organized support and calm classrooms. Another argument is that stricter migration policies will resolve the issue. Evidence suggests otherwise. Even with reduced intakes, Australia remains one of the world’s most diverse educational systems. Falling migration rates make integration for each student more critical, since each lost learner stands out more in a smaller group. The best response to these critiques is straightforward: design better schools and demonstrate the results. That is the mission of multicultural education policy.

Concerns about costs are valid. Early childhood places and teacher training incur expenses. However, delaying action is far more costly. Early childhood education narrows achievement gaps. Students who feel secure learn better and disrupt less. Communities that witness fair progress are less likely to support radical politics. These benefits accumulate over time, resulting in higher incomes, lower remedial education needs, and a more peaceful public life. Some funding has already been allocated to skills and immigration budgets. Additional funds can be identified by eliminating ineffective programs: long, isolated reception tracks, paperwork that delays enrollment, and fragmented tutoring that fails to link to the curriculum. The goal is a system that operates quickly, teaches effectively, and focuses on what truly matters. That epitomizes a lasting multicultural education policy.

The overall statistics will continue to change. Visa fees will increase. Caps and quotas will fluctuate. Net migration will rise and fall. Yet, one reality remains. A third of Australians were born overseas, and our classrooms already reflect the future. Through our multicultural education policy, we can choose whether that future is strong or fragile. This choice is practical rather than ideological. Assess language early and teach it well. Ensure classrooms are calm and safe. Invest in teachers and monitor progress by cohorts. Learn from successful models and adapt them to our context. If we do this, the opening statistic—one in three—will represent an asset rather than a challenge. If we don’t, that same number will be a source of division. The center will hold if we build it. Australia has successfully attracted people. Now we must smartly design schools that convert arrivals into opportunities, both rapidly and broadly. That is how a diverse democracy remains strong and vibrant, and that is how we make the numbers work for us.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

ACER. (2023). PISA 2022: Australian student performance stabilises while OECD average falls.

ACER. (2024). PISA reveals student experiences that help – and derail – maths performance.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2023). Overseas Migration, 2022–23 financial year.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2024). Australia’s population by country of birth, June 2023.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2022). Cultural diversity: Census, 2021.

Department of Education (Australia). (2023). Migration Strategy—International education.

Department of Home Affairs (Australia). (2023). Migration Strategy.

European Commission. (2025). Action Plan on Integration and Inclusion 2021–2027: Education and training progress tracker.

Eurostat. (2024). EU population diversity by citizenship and country of birth.

KPMG. (2025). Immigration-Related Measures in Federal Budget 2025–26.

OECD. (2023). PISA 2022 Results (Volume I): The State of Learning and Equity in Education. OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2023). PISA 2022 country note: Australia.

OECD. (2024). Education Policy Outlook 2024. OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2024). International Migration Outlook 2024. OECD Publishing.

Reuters. (2024, July 1). Australia doubles foreign student visa fee in migration crackdown. https://www.reuters.com

Treasury (Australia). (2023). Intergenerational Report 2023. Commonwealth of Australia.

Alieva, A. (2024). The progression of achievement gap between immigrant and native students and the role of ECEC. Economics of Education Review.

Comment