When Families Become a Nation’s Shock Absorber: Intergenerational Risk-Sharing in an Aging World

Input

Modified

Families insure children’s income shocks—cash for short hits, saving for long ones In ageing, low-growth countries, this scales nationally: Japan’s seniors work longer to steady households Policy fix: public “reinsurance” via income-linked tuition, midlife upskilling, and flexible senior roles in education

In 2024, a momentous shift took place in Japan's workforce: 25.2% of the population aged 65 and over were employed, marking the highest rate among major economies outside Korea. For the 65–69 age group, the figure was 52.0%, and for those aged 70–74, it was 34.0%. These substantial changes reflect a structural response to ongoing income risk in families and a declining workforce. Families, traditionally a source of support for their children during financial downturns, are now adapting to prepare for long-lasting financial shocks. They are saving more, working longer, and delaying retirement. Intergenerational risk-sharing, once a private family matter, has evolved into a national strategy aimed at sustaining the economy. While this approach has proven effective for temporary shocks, the question remains: will it withstand permanent changes?

Intergenerational risk-sharing begins at home

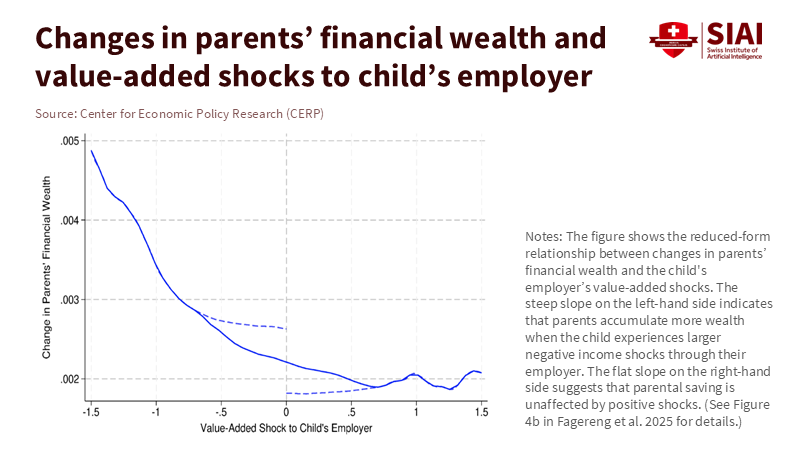

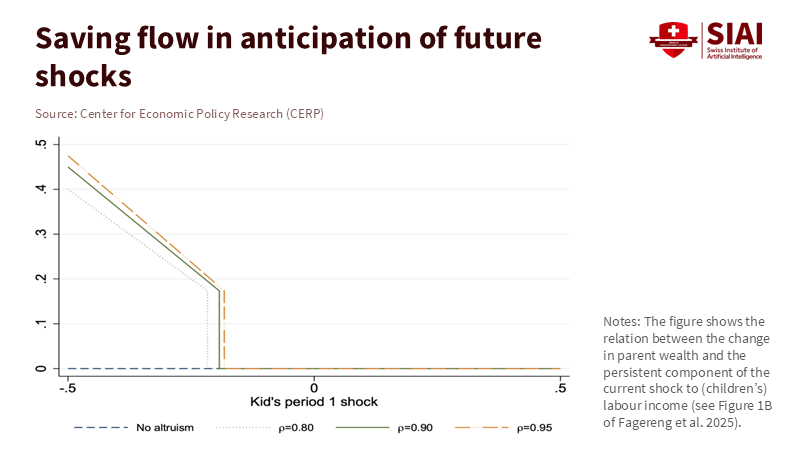

The system of intergenerational risk-sharing is straightforward in principle. Families step in to support each other when markets and public programs fail. New data from Scandinavian administrative records demonstrate this in action. When adult children face temporary income loss, parents use their savings to provide cash transfers. However, if the losses persist, parents adjust their strategy. They increase their savings to create a buffer for future support. These transfers from parents cover about 43% of temporary losses and 27% of ongoing losses. Notably, parents do not provide assistance when their children’s income rises, indicating that this is truly insurance rather than a gift tied to success. The system is nuanced. Parents provide direct help where other support systems are lacking. If a spouse can increase work hours or if unemployment benefits are adequate, families contribute less. This trend suggests that private and public insurance can work in tandem. In areas where state support is weak, family support grows. Where public policy is solid, families can conserve their resources for risks beyond the state’s reach. However, this division of responsibilities is effective but also fragile. It relies heavily on parents’ financial stability and work capacity to endure when their children’s financial challenges shift from temporary to lasting.

This logic is also relevant for educators and administrators. Parents who experience income or hour losses during economic downturns often rely on grandparents for childcare and financial support. College and school staff recognize this from case notes and financial aid records. When tuition gets paid or a laptop appears after a family setback, the hidden supporter is often a parent’s savings. The takeaway is clear: intergenerational risk-sharing helps students stay enrolled, supports trainees in completing programs, and assists early-career teachers and researchers during tough years. The risk is equally evident. If financial shocks persist for months or years, parents may start to conserve resources. The funds that stabilized one semester may not cover a full degree.

Intergenerational risk-sharing at the national level: Japan’s Type C shift

Japan illustrates the impact of a widespread belief that economic shocks are prolonged. Low fertility rates, rapid aging, and constrained job markets have turned millions of families into permanent safety nets. The national statistics reveal a stark reality. One in four people aged 65 and older is working; for those aged 65–69, the share exceeds 50%. Businesses report severe labor shortages. In 2024, labor-related bankruptcies rose by 32%, the highest ever recorded. Companies are responding by increasing wages, automating, and, importantly, retaining older workers. Beginning in April 2025, employers must provide continued employment up to age 65, including for smaller firms. Surveys indicate a strong willingness among seniors to work longer, often beyond age 70, motivated by financial needs, health, and a sense of purpose. This is intergenerational risk-sharing embedded within labor laws and business practices. Parents and grandparents work not just to support their own retirement but also to stabilize their extended families as inflation, caregiving costs, and unstable youth jobs strain younger budgets.

The education sector is feeling the effects. Schools and universities are hiring more late-career professionals for part-time teaching and advisory roles. Lifelong learning is becoming an essential workforce strategy rather than an enrichment program. Companies are reallocating training budgets to retrain older workers for digital competencies and crucial safety roles. Community colleges and local education centers in Japan report rising demand for brief, modular courses designed to fit around part-time work. This trend is not merely superficial; it serves as a funding source. When seniors increase their earning potential, families are better equipped to help younger generations manage tuition increases, unpaid internships, and career transitions. But there is a downside: older workers may need more flexible hours for caregiving, and businesses must redesign jobs to maintain productivity as the average age of employees rises. Without planning, intergenerational risk-sharing could turn into an unfair burden on older workers.

The decisions driving intergenerational risk-sharing in Japan are primarily economic, not cultural. Japan’s demographic situation is critical: fewer births, longer lifespans, smaller cohorts entering the job market, and a pension system under pressure. In this context, keeping seniors engaged in the workforce is not a choice; it is a means of financial stability that families rely on and that educational institutions and employers need to reinforce.

Intergenerational risk-sharing across Europe: the Greece challenge

Europe faces a less severe but similar situation. The EU loses about one million workers each year as the population ages. The old-age dependency ratio hit 33.9% on January 1, 2024. In Greece, the proportion of the population aged 65 and older was 23.3% in 2024, with fertility rates around 1.3–1.4, well below replacement levels. Policymakers are now presenting demographic changes as a national risk. In 2024, Greece introduced a multi-year plan to invest up to €20 billion by 2035 to increase the birth rate. They announced €1.6 billion in relief measures in 2025 to combat population decline. These are clear indicators that the state aims to shoulder more responsibility. However, high rates of youth emigration following the debt crisis and a still-weak wage structure mean families continue to bear the brunt of support—parents fund courses to keep their children job-ready. Grandparents take on childcare responsibilities so their daughters can work. Adult children are moving back home to save money. This is again intergenerational risk-sharing, but in a low-growth environment where families have less financial flexibility than in northern Europe, leading to stricter trade-offs.

Education leaders in Greece and similar economies cannot afford to wait for demographic changes. However, they can transform how financial risk is distributed across generations. Micro-credentials that accumulate toward degrees make it easier to manage costs when money is tight. Income-share agreements with set minimums turn tuition into a contingent claim on future earnings, mirroring the private risk-sharing families already practice. Vouchers for high-quality childcare during exam periods improve course completion rates. These measures do more than assist a handful of students; they lighten the load on older relatives, reducing the need for them to work longer or sell assets to make ends meet. The objective is clear: to restore intergenerational risk-sharing to institutions that are designed to manage it.

The alternative is evident during economic downturns. In the Asian financial crisis of 1997–1998, Korean families sold their assets to help their children weather temporary job losses. Unemployment tripled at its peak, consumption declined, and saving patterns fluctuated as families tried to recover their financial stability. That was a Type B dynamic: emergency assistance for temporary hardships. Many countries still rely on this approach. Today’s challenges—climate change, automation, slow economic growth, aging—appear more like seasonal shifts than isolated storms. Households recognize this reality. They plan for a Type C future and take action before policymakers react.

A policy framework for intergenerational risk-sharing

If families serve as the primary insurers, the public sector should act as the backup. The aim is not to replace family support but to enhance it responsibly. This requires three key steps. First, align education financing with income risk. Flexible, income-linked repayment options for higher education can reduce the fear of default and allow families to save for genuine emergencies. These programs should be straightforward, automatic, and limited, with clear forgiveness policies. Second, strengthen midlife training for parents. When parents can improve their income at 55 or 60 through focused short courses, they can share financial risks with their children without jeopardizing their retirement. This is not merely an advantage; it is the foundation for sustainable intergenerational risk-sharing. Third, incorporate migration and later-life work into schools' and colleges' staffing strategies. The EU’s annual shortfall of one million workers cannot be solved by higher birth rates alone. Legal migration pathways and structured second careers for retirees can help stabilize the education workforce across various roles, from classroom aides to IT support to specialized teachers.

These are systemic choices that have real implications in classrooms. School leaders can design schedules that accommodate caregivers’ needs. Universities can develop curricula in partnership with employers who hire older workers. Teacher training can include courses focused on multigenerational learning environments, as more classrooms will consist of older students. Procurement can prioritize technologies that enhance safety and reduce physical demands on older employees, ensuring they remain productive. All of these initiatives maximize the benefits of intergenerational risk-sharing by strengthening the family’s financial support network—parents and grandparents who choose to stay in the workforce.

Concerns about these strategies are understandable. One objection is that relying on older workers deprives younger individuals of opportunities. Data from Japan suggests the opposite in tight labor markets. Employers hire older workers because they cannot find enough young talent. Another concern is that family support might exacerbate inequality, as wealthier parents can provide more assistance. This is a valid issue, which is precisely why public backup is essential: progressive educational financing, generous childcare and disability support, and minimum income protections can help reduce disparities in private family support. A third worry is burnout among older workers. However, this is a design issue, not an unavoidable outcome. Flexible working hours, ergonomic improvements, and thoughtful role redesign can sustain productivity without overburdening older employees. When these conditions are met, the macro and micro aspects align: families provide insurance, the state acts as a backup, and educational systems channel both into human capital rather than temporary fixes.

Evidence from Norway highlights the potential for effective alignment. Families respond strongly to the income losses their children face, and they do so intelligently based on the nature of the challenge. They provide less support when other options are available and more when their child's situation is precarious. Policymakers should take this as guidance. By building robust alternatives—better employment opportunities for spouses, fair unemployment benefits, and predictable, income-linked tuition—families can avoid depleting their savings or delaying retirement as often. In essence, sound policy can enhance private support by reducing the pressures on it. Poor policy increases strain.

The challenge ahead is whether educational systems can view intergenerational risk-sharing as an essential element of their design rather than a mere background issue. This means collecting data on where family support is most crucial—whether for fees or basic needs, digital access or transportation—and sharing it in ways that are valuable to local leaders. It also means setting clear goals: reducing dropouts related to income shocks by a third within three years, increasing course completion rates for older learners by ten percentage points, and doubling the number of schools that offer flexible schedules for caregivers. These targets are attainable and represent the institutional equivalent of the quiet efforts families are already making.

We started with a simple observation: seniors in Japan are working at record levels, and this decision is part of how families help younger generations survive long-term financial shocks. This situation is crucial in shaping the decade ahead. Intergenerational risk-sharing has evolved from individual family practice to a national policy. The risk is that we take this for granted without implementing safety measures. If we do nothing, parents will continue to save more, work longer, and postpone their own rest to support their children. Such a system will eventually buckle under the pressure. The better approach is to meet families halfway. Create education financing that adjusts to earnings, provide midlife training to boost parents' incomes, and expand legal immigration to alleviate workforce shortages. Keep older workers in the job market by choice and with respect, not out of necessity and stress. If we act now, families can remain what they have always been—a primary line of support against income risk—while schools, colleges, and the government offer the enduring backup that only institutions can deliver. This is how we transform private sacrifices into collective resilience.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

AP News. (2024). The EU loses about a million workers per year due to aging. Migration official urges legal options.

Carneiro, P., et al. (2024). Insurance against Income Shocks, Parental Investments, and Child Outcomes: Evidence from Norway.

CEPR (2025). DP20632: Insuring Labor Income Shocks: The Role of the Dynasty.

Eurostat. (2024). Population structure and ageing.

Hellenic Statistical Authority (ELSTAT). (2025). Greece in Figures, Q2 2025.

HR Asia. (2023). Majority of Japanese still want to keep working after retirement age.

Japan Times. (2025). More older people choosing to work for social connection and purpose.

Leglobal. (2025). Japan: Looking ahead 2025.

Nippon.com. (2024). Number of seniors in employment continues to rise in Japan.

Reuters. (2024). Greece to spend €20 billion to lift low birth rate.

Reuters. (2025). Japan firms face serious labour crunch from aging population, survey shows.

SSRN. (2025). Insuring Labor Income Shocks: The Role of the Dynasty. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5487078

Trading Economics (Eurostat feed). (2024). Greece – Proportion of population aged 65 and over.

World Economic Forum. (2024). Senior employment in Japan could help solve worker shortages.