Reciprocal Tariffs and the Supreme Court: What Schools Need to Know

Input

Modified

Reciprocal tariffs face a Supreme Court test over presidential authority They raise import prices, squeezing school budgets and families Targeted trade tools and smarter procurement beat blanket tariffs

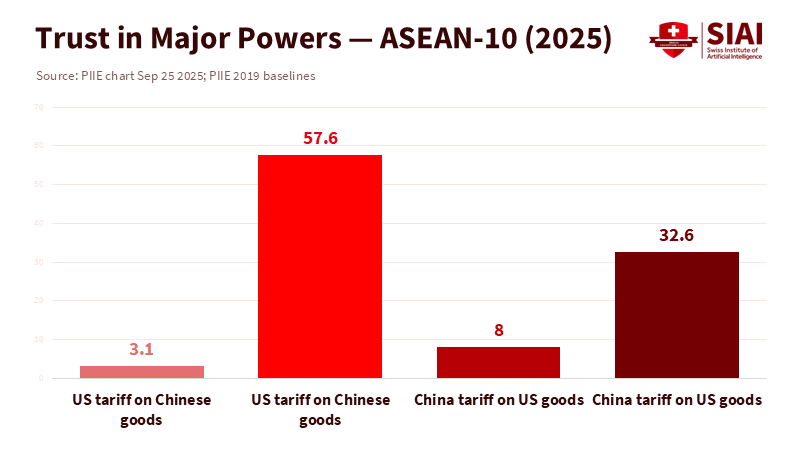

The stakes are clear and significant. By late September 2025, the United States was charging an average tariff of 57.6% on imports from China and 19.5% on goods from the rest of the world. These rates affected nearly all products and were much higher than the norm before 2018. They impact every device, lab supply, book component, and bus part that schools purchase. Analysts estimate the tariffs amount to about $1,300 in taxes per U.S. household this year. This cost does not disappear at the school door. It appears in district bids, affects campus budgets, and shows up in families' tuition bills. The legal case currently in the U.S. Supreme Court will determine whether this tariff system can remain in place. However, the impact on education is already evident, stemming from one policy idea: reciprocal tariffs.

Reciprocal tariffs and the two core requirements

The legal question centers on two rules governing the president's use of emergency economic powers. First, there must be an "unusual and extraordinary threat" coming from outside the United States. Second, the actions taken must directly address that threat in a concrete way. The reciprocal tariffs announced in 2025 were justified as a response to trade deficits and perceived unfairness in trade relations. Lower courts reviewed this rationale and found it lacking, ruling that the tariffs exceeded the authority granted to Congress. The case is moving quickly through the courts, with arguments set for early November. The outcome will clarify the boundary between Congress and the White House on trade. The Supreme Court will likely consider not only the wording of the emergency statute but also the historical practice of Congress setting tariffs. At the same time, the President implements laws within precise limits.

The most relevant precedent is United States v. Yoshida International (1971), where a temporary import surcharge was upheld because it was based on wartime emergency law and remained within earlier tariff ceilings. That case shows the Court's caution: specific, time-limited measures can be approved; broad, indefinite tariff changes usually cannot. Recent appellate decisions highlight the same point. The Federal Circuit's August 29 ruling outlined how the 2025 reciprocal tariffs were introduced by declaration. It was then repeatedly altered by executive order, which contradicted the claim that they were narrowly focused on a defined foreign threat. The ruling also noted the constitutional principle that Congress holds the tariff power and that any delegation must be explicit. The Court will assess whether reciprocal tariffs meet that standard.

Why reciprocal tariffs fail in court and in economics

Even if reciprocal tariffs fit the statute's language, they face an economic barrier. Evidence from the 2018–2019 trade war indicates that tariffs were mainly passed through to U.S. import prices. Importers and consumers bore the cost, with no significant price concessions from foreign sellers. Recent work from the Atlanta Fed confirms this finding: tariff increases led to higher prices at the border and in stores. When we consider average tariff rates above 50% for a major supplier and near 20% for the rest of the world, we should expect significant price pressure. This aligns with private-sector and policy models that translate tariff schedules into household costs. The recent estimate of approximately $1,300 per household in 2025 reflects this pressure.

The legal basis for reciprocal tariffs also misinterprets trade realities. Trade deficits do not prove unfair barriers; they reflect savings and investment patterns across various partners. Demanding "reciprocity" through broad tariffs overlooks how past agreements have reduced average tariffs while balancing benefits among sectors and countries. This approach also invites retaliation. The current tariff situation illustrates how quickly and broadly retaliatory measures can escalate. By late September, the average U.S. tariff on Chinese goods was 57.6%, while Chinese tariffs on U.S. exports reached 32.6%. These levels affected all products. Such extensive taxes are ineffective for addressing specific supply issues, and they do not align with the emergency law's expectations for clear connections between cause and solution.

What reciprocal tariffs mean for education systems

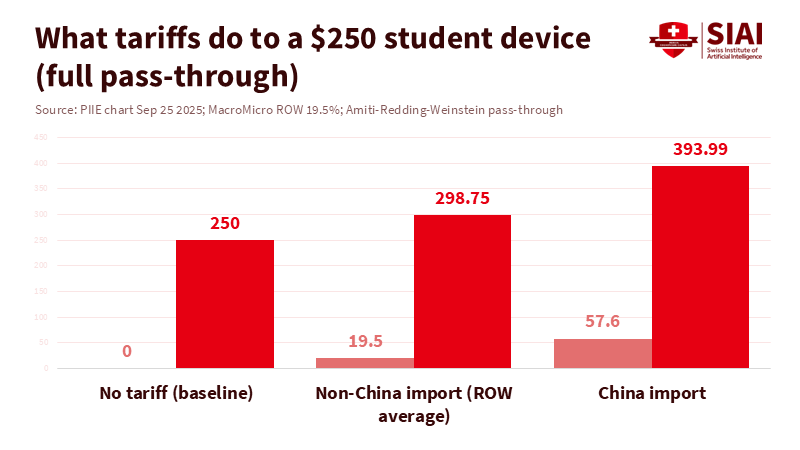

The education sector is affected by tariffs in three main ways: procurement, payroll, and learning conditions. Procurement is the most direct impact. Districts continue to buy large numbers of devices, many of which are low-cost laptops priced around $250 in regular times, with tablets costing more. A nearly 20% average tariff on non-China imports, along with much higher rates on Chinese goods, causes bids to rise quickly when suppliers source parts from abroad. Evidence shows that these price increases generally appear in quotes. Device refresh cycles are extended, leading to aging fleets that raise maintenance costs. These challenges arise alongside tight post-COVID budgets. Census data indicate that per-student spending increased by 5.7% in 2023, with many states catching up on deferred needs. Still, those gains must cover salaries, transportation, food, and maintenance. Tariff-driven price hikes limit funding for these fundamental needs.

The second impact relates to payroll. In K–12 finance, salaries and benefits consume most current spending. When imported goods, ranging from bus tires to lab supplies, become more expensive, districts are forced to make tough choices: delay hiring and raises or delay purchases. Either choice compromises services. Studies of previous tariff rounds found that price increases were widespread and significant. There is no rational basis to expect different results now, given the much higher average rates. If reciprocal tariffs remain, districts will face higher baseline costs for everyday items. This situation is especially challenging for Title I schools that depend on low-cost devices and supplies. State equalization formulas do not adapt quickly enough to keep pace with vendor price changes.

The third impact affects learning conditions and equity. When device fleets age, software goes unpatched, and parts become scarce. A 2023 analysis warned that shorter device lifespans could cost schools billions over time. Tariff-driven price spikes complicate replacement plans and lead districts to ration resources unevenly. Students facing various challenges, such as new arrivals, rural learners, and low-income families, receive fewer working machines and experience longer repair wait times. High schools with advanced career and technical programs also feel the pressure since many of the tools and supplies for these programs are sourced globally. Reciprocal tariffs convert those inputs into unpredictable taxes. This volatility complicates planning and discourages new initiatives.

A better path beyond reciprocal tariffs

There is a constructive alternative to reciprocal tariffs that preserves supply chains without burdening schools. First, use existing trade laws as Congress intended: focused, rule-based, and evidence-based. Section 301 allows for action against unfair practices after a thorough investigation. Section 232 permits measures to tackle specific risks to national security within defined sectors. These tools require findings from expert agencies and create incentives for trading partners to reach agreements. Courts tend to show more deference when the executive branch follows this approach rather than when it claims broad emergency powers to overhaul the entire tariff system.

Second, bolster resilience through procurement and standards instead of blanket taxes. Federal and state buyers can combine demand for devices and lab equipment under clear security and transparency guidelines. They can require multiple sourcing and repairability to lower lifecycle costs. Schools and universities can ask vendors to disclose the origins of critical parts. These strategies lessen reliance on a single country without imposing burdens on all imports. In the short term, public consortia can secure prices before tariff fluctuations, giving schools a stable time frame for replacement cycles. Over the long term, standards for durability and the right to repair can lower total ownership costs more effectively than widespread tariffs ever could.

Third, invest in skilled workers rather than imposing trade barriers to revitalize manufacturing. A larger pool of qualified workers in chips, power electronics, and advanced assembly is the quickest way to enhance supply chains. Education leaders can collaborate with local employers to align career and technical education pathways, apprenticeships, and short-term training to meet the demands of modern manufacturing. These programs are not theoretical; they focus on the machines that districts purchase for classrooms and makerspaces. Making those machines more expensive through reciprocal tariffs undermines the goal of rebuilding. It is more cost-effective and sensible to subsidize training materials than to impose taxes on them, and this approach is legal in ways that broad emergency tariffs are not.

Addressing the critique. Some argue that tariffs generate revenue for public services, including schools. Revenue forecasts for 2025 and beyond are indeed substantial. However, this revenue isn't explicitly earmarked for classrooms, and its legal status is uncertain. If courts invalidate reciprocal tariffs, refunds and supply disruptions could follow. More critically, every dollar collected this way takes at least a dollar from households and institutions that must purchase the taxed goods. Evidence shows that consumers ultimately pay. Education budgets suffer twice when higher procurement costs collide with stagnant wage growth and weaker local tax revenues. In summary, the idea of "funding via tariffs" is an illusion for schools.

Addressing the other critique. Some claim that reciprocal tariffs are necessary to compel partners to play fair. However, the 2025 situation demonstrates that when one side imposes broad taxes, the other can respond in kind, with widespread consequences. By September, both countries had tariffs impacting 100% of bilateral trade at high average rates. This scenario offers no leverage; instead, it creates a deadlock that affects every supply chain, including the education sector. Targeted agreements, along with enforcement actions following legal procedures, have a better historical record of producing results.

The significant tariff rates—57.6% on Chinese goods and 19.5% on imports from the rest of the world—are not abstract figures. They explain why a district delays updating its device inventory, why a university lab waits months for parts, and why families see fees rise throughout the year. The Supreme Court now faces a crucial question: do reciprocal tariffs meet the statute's two core requirements, and does the executive branch have unchecked authority to tax everything under the pretense of an emergency? The legal answer matters, but education leaders shouldn't delay. They can focus on pooled purchasing, durability standards, and skills development to reduce costs and build resilience. Policymakers can revert to targeted trade enforcement that addresses real issues without straining schools. That route leads to lower prices, better tools, and enhanced learning. It starts with acknowledging an uncomfortable truth: reciprocal tariffs create barriers that classrooms ultimately pay for.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Amiti, M., Redding, S., & Weinstein, D. (2019). The Impact of the 2018 Trade War on U.S. Prices and Welfare (NBER Working Paper 25672).

Amiti, M., Redding, S., & Weinstein, D. (2020). Who's Paying for the U.S. Tariffs? A Longer-Term Perspective (NBER Working Paper 26610).

Atlanta Fed Policy Hub (2025). Tariffs and Consumer Prices (Policy Hub 2025-01).

Bown, C. P. (2025, September 25). US-China Trade War Tariffs: An Up-to-Date Chart. Peterson Institute for International Economics.

Census Bureau (2025, May 1). 2023 Annual Survey of School System Finances (Press Release CB25-TPS.30).

CEPR VoxEU (Grossman, G. M., & Sykes, A. O.). (2025, October 27). The flawed rationale behind America's "reciprocal tariffs".

EdWeek (2025, May 6). Schools Brace for Tariff-Related Price Increases of Chromebooks and iPads.

EdWeek (2023, April 26). Chromebooks' "Short" Lifespans Cost Schools Billions, Report Finds.

EY (2025, September 9). U.S. Supreme Court will hear oral arguments in tariff case in early November 2025.

NCES (2024, May). Public School Expenditures. Condition of Education Indicator CMB.

Tax Foundation (2025). Tariffs and Trade Policy. (Tariffs ≈ $1,300 per household in 2025).

U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (2025, August 29). V.O.S. Selections, Inc. v. Trump (No. 25-1812) (Opinion).

Wolff, A. W. (2025, October 7). What should guide the Supreme Court's decision on Trump's tariffs? PIIE RealTime Economics.

Wolff, A. W. (2025, July 31). Trump tariffs and the courts: Round 2. PIIE RealTime Economics.