Japan’s Second Act and Southeast Asia’s First Choice

Input

Modified

Japan rearms as Russia–China aligns ASEAN trusts Tokyo yet wants guardrails Education builds consent via maritime literacy

The key number is 66.8. This is the percentage of Southeast Asian opinion leaders who trust Japan to "do the right thing" regarding peace and stability, according to ISEAS’s 2025 regional survey. It is the highest level of trust toward any significant power in the area. Contrast this with the reality that Japan is rearming at a rate not seen in its post-war history, moving toward a defense budget of 2 percent of GDP and purchasing 400 U.S. Tomahawk missiles. Trust and military strength are both increasing, creating a paradox we need to address. Japan's rearmament and Southeast Asia's response will determine whether the next decade promotes stability through rules or plunges into a continuous arms race. The opportunity to establish regulations is now, while trust is still strong and before military hardware creates habits. The region can influence this rearmament if it takes an active rather than a passive role.

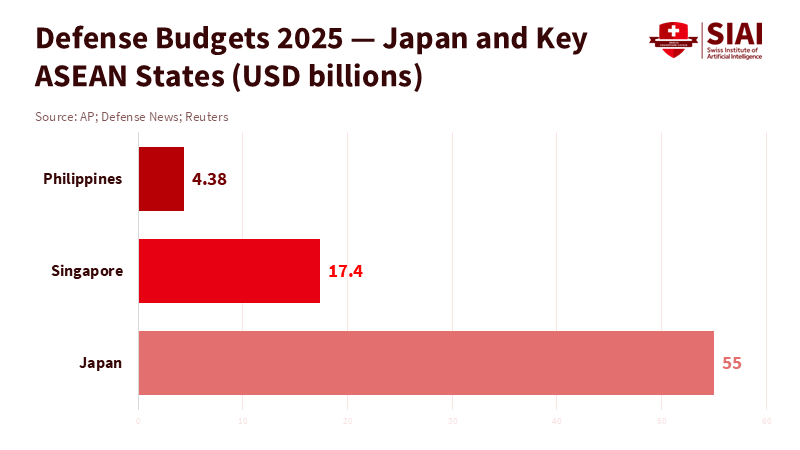

Global military spending rose 9.4 percent in 2024, marking the most significant annual increase since at least 1988 and reaching $2.718 trillion. Japan’s decision to boost defense spending does not happen in isolation; it is part of a broader security crisis affecting the South China Sea, Taiwan, and the Russia–Ukraine war. In Southeast Asia, defense budgets are increasing in response to actual risks: Singapore’s 2025 defense plan rose to S$23.4 billion (about 3.2 percent of GDP), and the Philippines increased its 2025 allocation to 256.1 billion pesos to strengthen external defense following conflicts over the Second Thomas Shoal. These reflect genuine concerns, not mere rhetoric. The current challenge is to turn increased spending and Japan’s rearming into a stable order that the region recognizes as its own.

The motivation for this rearmament is not just China's rise, but also the Russia–China "no-limits" partnership. In 2024 and 2025, Beijing and Moscow enhanced military cooperation, including joint naval and submarine drills in the Sea of Japan and the Pacific. Their leaders announced a "new era" of collaboration that explicitly rejects U.S.-led alliances. This closer alignment forces U.S. allies and partners to unite, as evidenced by Germany’s renewed defense efforts in Europe and Japan's counterstrike strategy in Asia. Memories of the 1930s and 1940s remain significant in Korea and Southeast Asia. These memories influence the political climate. The region must come to terms with historical trauma while also focusing on current deterrence. This means establishing legal, political, and educational frameworks around Japan’s return to military power, especially while trust in Tokyo is high.

Japan's rearmament and its effect on Southeast Asia: the trust paradox

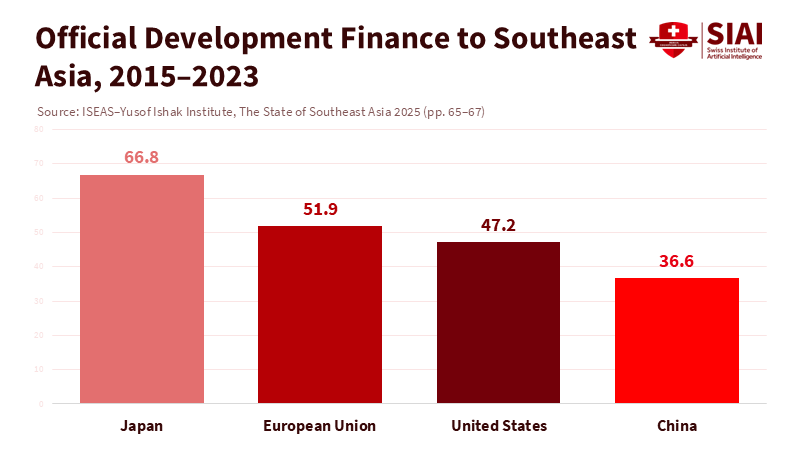

Here’s the central point: Japan is Southeast Asia’s most trusted outside partner—66.8 percent trust on average across ASEAN in 2025, with levels above 80 percent in the Philippines. This trust developed over decades through aid, industrial investment, and responsive actions during crises. It has persisted even as tensions with China have increased and U.S. policies have become less reliable. However, trust is not unlimited. It requires careful management. Tokyo has already adjusted its security policy in ways that impact Southeast Asia: easing export rules to permit Patriot missile transfers to the U.S., approving potential exports of the UK-Italy-Japan GCAP fighter to select partners, and launching Official Security Assistance (OSA) that supplies non-lethal equipment—from coastal radars to rescue boats—to early recipients such as the Philippines and Malaysia. Each adjustment broadens Japan’s role and increases interdependence. The region's task is to determine how this entanglement can enhance its own security and benefit its citizens.

Trust is tested in real situations. In 2024, Chinese coast guard ships repeatedly used water cannons against Philippine vessels near Second Thomas Shoal, causing injuries to sailors and damaging boats. Vietnam monitored incursions near Vanguard Bank. These incidents are real and push Southeast Asia toward partners willing to share risks, information, and resources. Japan’s Reciprocal Access Agreement with the Philippines, signed in July 2024 and effective since September 2025, legally supports training, logistics, and access.

Meanwhile, Tokyo's Tomahawk purchase and counterstrike policies adjust the balance of power around the First and Second Island Chains. If these capabilities are viewed as unwelcome interference, trust will fade. However, if they align with regional needs—like maritime security, law enforcement, and crisis communication—trust can develop into lasting approval.

From Germany to Japan: rearmament with safeguards

Europe provides both a warning and a model. Germany reached NATO’s 2 percent defense spending target in 2024 for the first time in 30 years and has continued to increase spending since. Yet its leaders still emphasize sustainability and democratic oversight following the disruptions of war in Europe. The point here is not about historical guilt; it’s about creating safeguards. Southeast Asia should advocate for three safeguards as Japan's rearmament progresses. First, ensure OSA is driven by demand and transparency by publishing project criteria, conditions of use, and independent audits. Second, link export reforms to clear rules: no transfers to ongoing conflicts, strict re-export agreements, and public reporting of co-production processes. Third, integrate new access agreements—like the Japan-Philippines RAA—into an ASEAN-plus code of conduct for exercises, logistics, and incident response, in line with the 2016 arbitration ruling on the South China Sea. These safeguards won’t hinder deterrence; they will legitimize it.

Now a word about the larger strategic context. The Russia–China partnership is not a formal alliance. Still, its effects resemble those of one at sea and in the air: joint submarine patrols, coordinated drills, and statements that portray U.S. alliances as destabilizing. This dynamic is drawing Germany and Japan closer to the United States and to each other, not a longing for pre-1945 dominance. The lesson for policymakers is clear: if the region wants rearmament to promote stability rather than escalate tensions, regulations must go hand in hand with military strength, and community support must accompany military capability. Europe learned this the hard way; the Indo-Pacific can proactively incorporate these lessons.

Educators and administrators: what to do now

Education systems play a crucial role in security. They are the frontline for building trust. First, revise curricula and teacher training to include a realistic view of Japan’s 20th-century occupation alongside post-war reconciliation, Official Development Assistance, and today’s rules-based maritime order. This approach does not aim to downplay the past but to equip students to recognize two truths: the trauma was real, and the trustworthy partner of today is also real. Second, develop regional student exchanges, collaborative STEM labs, and maritime vocational programs that support OSA initiatives. When a coastal radar is installed, invest in local technical college training and create a school-to-service pipeline for maintenance and data analysis. Third, enhance public knowledge of maritime law basics, AIS data, and how to understand Coast Guard statements, so that public discussions are informed rather than driven by sensational social media moments during maritime confrontations. These efforts may seem small each year, but their impact will compound over time.

Administrators can act even more quickly. Universities and teacher colleges should create "trust and security" projects with Japanese and Korean partners that combine historical perspectives with current policy simulations. Education ministries can test school-based alert systems in coastal areas that connect with civil defense and coast guard communications, ensuring facts are conveyed during incidents rather than rumors. Educational technology providers can adapt open satellite and AIS feeds for classroom engagement, making maritime domain awareness a civic habit. These initiatives require comparatively little investment relative to new ships and missiles. Still, they cultivate support in the communities that will endure increased tensions even if deterrence succeeds. Japan’s rearmament in Southeast Asia should translate into student skills, not just military might.

Addressing the toughest critiques

One critique claims that rearmament will inevitably revive militarism. Current evidence suggests otherwise. Japan's export policies are limited—providing finished products to treaty partners, confining GCAP sales to approved countries, and banning transfers into active conflicts. OSA focuses on non-lethal equipment that enhances maritime law enforcement rather than military aggression. Japan is also establishing legal ties, not military bases, in Southeast Asia. While this does not eliminate risk, it offers a path that avoids both inaction and provocation. The essential question remains: Are Southeast Asian priorities—protection of infrastructure, coastal livelihoods, and fisheries enforcement—guiding military acquisitions and training? If not, push for more accountability.

Another critique posits that trauma never fades, suggesting public support will weaken under pressure. Surveys present a more complex reality. Korean attitudes toward Japan have reached historic highs in 2024–2025, even amid political tensions. In Southeast Asia, trust in Japan has increased for two straight years, surpassing that of all other foreign powers. This doesn’t erase past pain, but it opens the way for constructive policies. The goal should be to use this moment to establish conditions—transparency, end-use monitoring, and educational initiatives—that help maintain trust during future crises. If the region allows this opportunity to slip away, the narrative of "a return to 1940" will fill the void. There is still a chance to steer things in a better direction.

The notable figure—66.8 percent trust—has dual implications. It reflects the reward of years of consistent Japanese engagement and serves as a commitment to a more uncertain future. Japan's rearmament and its impact on Southeast Asia are not just slogans; they require ongoing effort to translate increased budgets and improved tools into a security framework that people find. The Russia–China partnership will continue to challenge the region. Incidents at sea will repeatedly test resolve. However, trust is a form of power, and Southeast Asia has greater trust in Tokyo than in any other significant power. Suppose policymakers and educators harness this trust to implement safeguards, build capabilities, and insist on transparency. In that case, the region can achieve the best outcome: a Japan that deters without dominating, and a Southeast Asia that writes its own security rules rather than following them after the fact. The time to solidify this is now—before military hardware influences behavior.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Associated Press. (2024, March 23). Chinese coast guard hits Philippine boat with water cannons in disputed sea, causing injuries.

Associated Press. (2025, October 24). Japan’s new leader vows to further boost defense spending as regional tensions rise.

Defense News. (2025, March 7). Singapore raises defense budget, readies new military acquisitions.

International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS). (2024, August 19). New opportunities and old constraints for Japan’s defence industry.

ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute. (2025, April 3). The State of Southeast Asia 2025 Survey Report.

Japan Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA). (2025, October 7). Joint Committee Meeting under the Japan–Philippines Reciprocal Access Agreement.

Japan Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA). (n.d.). Official Security Assistance (OSA) programme in Malaysia.

Nippon.com. (2024, March 27). Japan’s New Arms Export Policy: An Unfinished Agenda. Reuters. (2023, December 22). Japan prepares for missile shipments after easing arms export restrictions.

Reuters. (2024, March 26). Japan relaxes military export curbs for planned jet fighter.

Reuters. (2024, July 29). Philippines seeks increase in defence spending in 2025.

Reuters. (2024, May 17). Putin and Xi pledge a ‘new era’ and condemn the United States.

Reuters. (2024, March 23). China coast guard uses water cannons against Philippine ships in South China Sea.

Reuters. (2025, January 20). Germany met NATO’s 2% defence spending target in 2024, defence ministry says.

Reuters. (2025, September 18). Germany approves 2025 budget, ushering in new era of defence spending.

RSIS Policy Report. (2025, January). Japan’s Official Security Assistance to Southeast Asia.

SIPRI. (2025, April 28). Trends in World Military Expenditure, 2024.

The Diplomat. (2025, July 8). Japan steps up new security assistance to countries caught between the U.S. and China.

USNI News. (2025, September 17). Japan Destroyer Chokai will be Tomahawk missile-capable by March.