From Capital to Classrooms: The Demand Case for Southeast Asia Sovereign Wealth Funds

Input

Modified

The bottleneck is investable projects, not capital Build regulated grids and education contracts that generate steady, social returns With clear rules, Southeast Asia sovereign wealth funds can turn savings into national progress

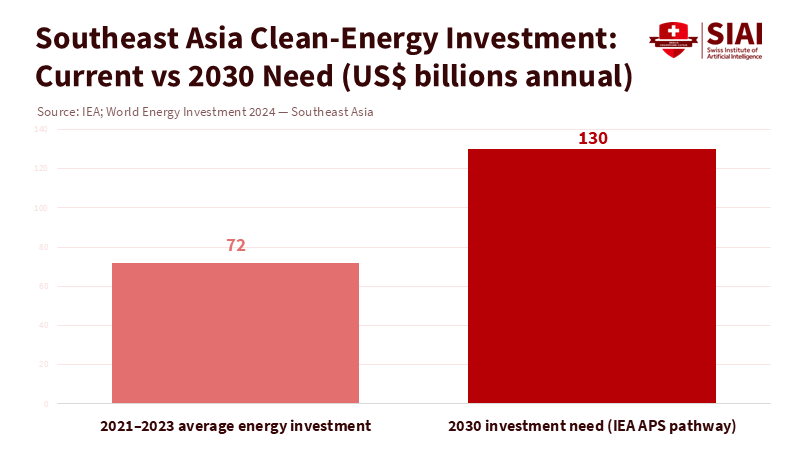

Southeast Asia's investment situation now hinges on a significant disconnect. The region's clean-energy spending averaged about USD 72 billion a year over the past three years. However, it needs to exceed USD 130 billion by the end of this decade to stay on a credible transition path. At the same time, 18 million children and teenagers in Southeast Asia are out of school. Climate shocks are forcing even more learners out of classrooms for weeks at a time. Capital isn’t the only constraint; the real issue is a shortage of investable projects that can turn money into public value on a large scale. This is why the conversation about Southeast Asia's sovereign wealth funds should shift from “who has the cash” to “where can that cash go.” The demand side, rather than the supply side, now drives the pace for the coming decade.

The demand case for Southeast Asia sovereign wealth funds

Debate often centers around which governments have surplus savings. The more relevant question is where those savings can be used effectively. Indonesia has created a two-track system. The Indonesia Investment Authority (INA) serves as a co-investment platform that brings in partners. Danantara, launched in 2025, is a larger investment holding fund supported by state assets to advance national priorities. The Philippines moved forward with the Maharlika Investment Corporation (MIC), which completed its first major deal in the critical grid infrastructure sector. This institutional redesign shows intention: make the state a long-term partner that can influence markets rather than follow them.

The mechanics are already apparent. Danantara began with an investment program of around USD 20 billion and has consolidated holdings in banks, energy, and telecoms. INA reports it has secured USD 25 billion in partner commitments since its inception and is expanding into digital infrastructure as demand rises. In January 2025, MIC acquired a 20% stake in the National Grid Corporation of the Philippines, securing its position in a regulated asset that supports resilience. These steps outline a demand-side thesis: create credible, cash-flowing projects first, then match them with patient capital.

The supply of capital is increasing more rapidly than the availability of investable projects. Gulf investors are shifting toward green assets and seeking partners across emerging Asia. This presents an opportunity, but only if local sponsors have standardized contracts, clear regulations, and reliable counterparties ready to proceed. Otherwise, new funds may pursue a limited number of high-profile assets, driving prices up and risking politicization. The current focus should be on building a pipeline, not launching new funds.

Green investment as the anchor demand

Power and grids should lead the way because they reduce emissions and provide stable, regulated cash flows. The International Energy Agency estimates that the region needs to increase clean-energy investment to roughly USD 190 billion per year by 2035—about five times the current amount. Grid spending alone must double to nearly USD 30 billion annually to keep up with demand and integrate renewables. That is a typical area for patient capital. When Southeast Asia's sovereign wealth funds co-invest with utilities and independent producers under transparent tariff rules, they finance public goods and secure bond-like returns.

The model is already evolving. In June 2025, Singapore’s DBS and UOB arranged a record 6.7 trillion rupiah loan for a DayOne-INA data center campus in Batam, marking INA’s first entry into digital infrastructure. The project's logic is straightforward: reliable power, efficient cooling, and secure connectivity in an industrial park with cross-border links. This same framework can be adapted to utility-scale solar, grid-support batteries, and port electrification—places where clear rules can convert engineering into investable cash flows.

A second growth avenue is cross-regional partnerships. Gulf and Southeast Asian funds are starting to coordinate on green platforms, with opportunities to blend concessional and commercial money for early-stage projects. By combining Gulf liquidity with ASEAN project initiation, the first movers can reduce risks for others. Local banks can then understand the asset class and reinvest in follow-on deals. This approach transforms isolated headlines into a consistent stream of projects.

Social infrastructure is investable when cash flows are clear

Education has often been seen as a cost center rather than an asset class. That perception is changing. Eighteen million young people in Southeast Asia are still out of school. At the same time, climate-related events disrupted the education of at least 242 million students worldwide in 2024. In the Philippines, UNICEF now advocates for climate-resilient schools and flexible teaching models following heatwaves, floods, and typhoons that interrupted learning. The need is vast and pressing, and the investment rationale is simple: turn school maintenance, resilience upgrades, and learning recovery services into predictable contracts that large investors can support.

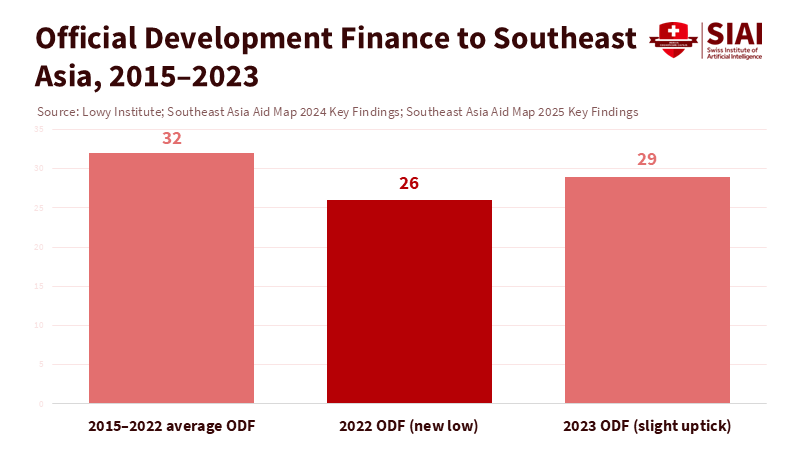

Public budgets are tight, and concessional aid isn't filling the gap. Official development finance to the region fell to a record low of USD 26 billion in 2022 after a brief surge during the pandemic. However, this does not mean social investment should wait. It means projects must be structured to attract domestic savings and institutional capital under public oversight. Energy service agreements that install solar panels on school rooftops and clinics can be repaid through lower utility bills, supported by government guarantees and provincial budgets. When well-structured, these contracts present low risk for investors and high value for communities.

Outcome-based education contracts can also connect funding with measurable learning improvements. Governments can fund tutoring or curriculum acceleration and pay based on independently verified reading outcomes, similar to those used in World Bank learning-poverty diagnostics. Southeast Asia's sovereign wealth funds could provide working capital to scale service providers, with repayments linked to results and capped to protect public value. The principle is straightforward: channel patient capital into reliable services and pay for outcomes that matter.

Governance that builds demand, not just balance sheets

Critics argue that state funds should focus on maximizing returns and leave social policy to public budgets. The response is that rules govern returns. Regulated grids, energy upgrades for schools, and outcome-based services have produced steady, bond-like profiles in many markets for years. Governance risk is a valid concern, but the solutions are practical. Publish standardized procurement templates. Protect green and social initiatives within fund charters. Create investment committees that operate independently and are publicly transparent. Use independent administrators to confirm outcomes. Clarify co-investment and exit rules so politics does not overshadow sound decision-making.

Multilateral banks are moving to support this transition. The Asian Development Bank aims to dedicate 50% of its annual lending to climate finance by 2030 while mobilizing more private capital. This public support can reduce risks for early deals and speed up learning across the ecosystem. National funds also show financial promise. INA reports growth in assets and partner commitments. At the same time, the Philippines' MIC announced first-year earnings and invested capital in the grid, a priority for resilience with regulated revenues. Maintaining a disciplined pipeline rather than focusing on large headlines will determine whether this momentum continues.

A practical mandate for a decisive decade

This is an opportunity, not a certainty. The transition is challenging, and the learning crisis is urgent. The region must shift from isolated announcements to a consistent, project-focused approach that enhances daily life while meeting climate goals. Begin with standardized contracts for school energy and maintenance. Expand grid concessions with clear tariffs and local currency protections. Tie sovereign co-investment to reported social outcomes. Then share performance data so successes can be replicated across borders and failures can be addressed early.

The current figures highlight the challenge. Clean-energy investment in Southeast Asia needs to double by the end of the decade, and millions of young people still lack access to education. Money is abundant. What is missing is the system that transforms capital into lasting public value. That system is a pipeline of viable projects with clear rules, prudent risks, and measurable outcomes. Build that pipeline, and Southeast Asia's sovereign wealth funds can transition from simple balance sheets to tools for nation-building. Failing to do so will mean the decade passes with funds sidelined and classrooms still waiting.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Asian Development Bank. “Capital Utilization Plan Expands Operations by 50% Over Next Decade.” Feb. 18, 2025.

Asian Development Bank Data Library. “Climate Change Financing at ADB.” 2024–2025.

BusinessWorld. “Maharlika wraps up first full year of operations with earnings of nearly P2.7B.” Oct. 26, 2025.

International Energy Agency (IEA). Southeast Asia Energy Outlook 2024 (Executive Summary and full report). Oct. 21, 2024.

International Energy Agency (IEA). “Southeast Asia – World Energy Investment 2024.” 2024.

International Energy Agency (IEA). “High cost of capital and limited project pipeline hinder clean energy investment in Southeast Asia.” Oct. 8, 2025.

International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS). “Could Gulf and Southeast Asian sovereign wealth funds lead global green investment?” Oct. 1, 2025.

Indonesia Investment Authority (INA). “INA has secured USD25 billion in investment commitments since its establishment.” Aug. 1, 2025.

Reuters. “DBS, UOB provide $411 million loan to DayOne-INA data centre project in Indonesia.” June 5, 2025.

Reuters. “Indonesia’s Prabowo officially establishes new sovereign wealth fund.” Feb. 24, 2025.

Reuters. “Philippines wealth fund buys into China-backed national grid operator.” Jan. 27–28, 2025.

UNESCO. “18 million children and teenagers are out of school in South-East Asia.” July 10, 2025.

UNICEF. “Nearly a quarter of a billion children’s schooling was disrupted by climate crises in 2024.” Jan. 24, 2025.

The Financial Times. “The rise of the trophy SWF.” April 2025.

The Lowy Institute. Southeast Asia Aid Map — 2024 Key Findings. June 17, 2024; and 2025 Key Findings. July 22, 2025.