Deposit Rate Elasticity Is the Weakest Link in Monetary Transmission

Input

Modified

Mortgage rates move fast; deposit rate elasticity stays weak Most households ignore higher yields; wealthy react more but leave money Clear benchmarks, auto-sweeps, and education can raise responsiveness safely

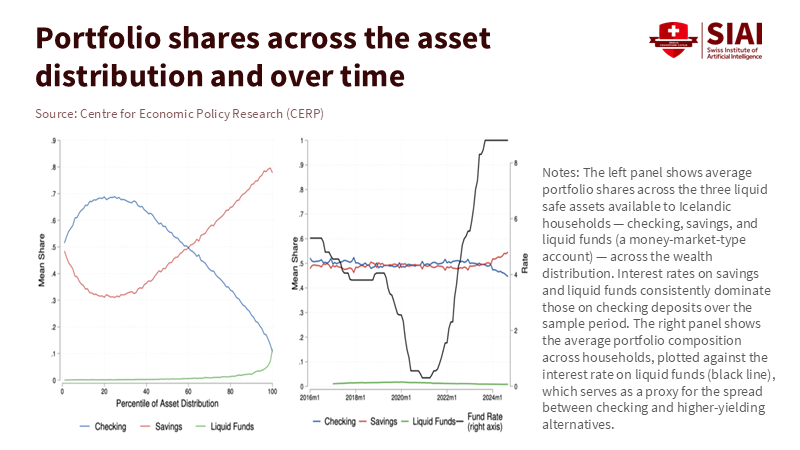

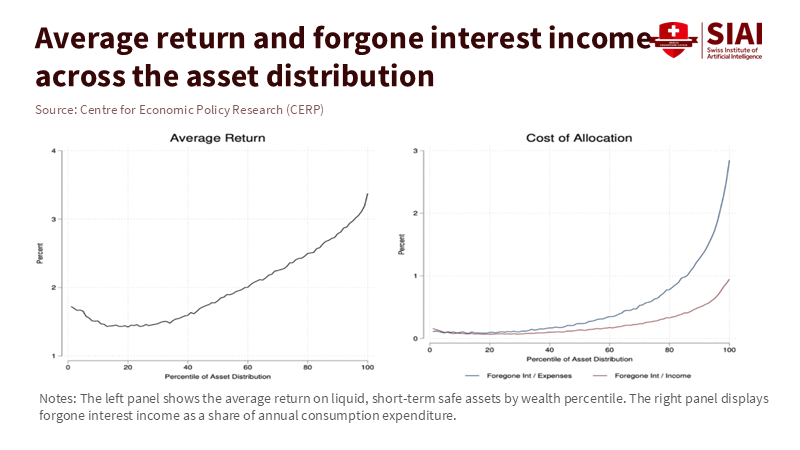

A single figure reveals a hidden flaw in the monetary transmission mechanism. In Iceland, when the difference between low-yield checking accounts and higher-yield liquid accounts increases by one percentage point, the average household cuts its low-yield deposits by only 0.1 percentage points. The wealthiest 10% do respond, but they still miss out on interest income that amounts to about 2.5% of their annual spending. These deposits are not unusual assets; they are safe, insured, and transferable by phone within seconds. Yet cash remains stagnant. If monetary policy depends on savers to seek higher yields, this is inadequate. In contrast, mortgages in the United States adjust almost instantly with the 10-year Treasury and respond quickly to economic changes. Mortgages adjust; deposits do not. The key takeaway is clear: deposit rate elasticity is the weak link, and the gap between what policy intends and what households do is widest where it should be narrowest.

From fast mortgages to slow money: the missing pass-through

Mortgage rates in the U.S. closely follow market yields. Lenders adjust their rates daily based on the 10-year Treasury; the weekly Freddie Mac survey captures these near-instant changes. From 2023 to 2025, the spread between mortgage and Treasury rates fluctuated with market stress. Still, the trend was consistent: long rates shift, mortgage quotes follow. That is why news about yields appears almost immediately on rate sheets. It also explains why consumers can lock in a rate in the morning only to find a different one by the afternoon. The main point is not that the Fed "sets" mortgage rates; instead, mortgage funding costs align with market benchmarks that change constantly, allowing lenders to pass these costs on quickly.

Deposits act differently. Banks pay what they must, not what they can, because retail funding is sticky. Evidence shows that when the policy rate rises by 100 basis points, banks widen deposit spreads and total deposits decrease—the “deposits channel.” Recent industry studies suggest a steady gap between fed funds and the average deposit rate, along with a partial monthly pass-through pattern. In practice, this means households feel much less impact from tightening than bond traders do. Even after the disruptions of 2023, when depositors briefly shifted funds and interest expenses surged, bank reports indicate that outflows stabilized. Deposits later increased, even with significant rate differences still in place. Monetary policy has a strong effect in markets where prices reset frequently, but a minor impact in markets where prices adjust due to habit. This asymmetry defines the overall issue of deposit rate elasticity.

Deposit rate elasticity

Recent data from Iceland support a familiar observation: most households do not respond to differences in rates across insured, liquid accounts. The typical reaction to a one-point spread increase is a 0.1-point shift away from low-yield balances. Wealthy households shift nearly ten times as much, but even they leave substantial sums untouched. Since deposits are concentrated among the rich, overall flows reflect the decisions of a small group rather than the average saver. Models based on typical “adjustment frictions” overestimate reality; they expect larger shifts than the actual data show. Consequently, the path of monetary transmission is weaker and more uneven than textbooks suggest. Simply put, measured deposit rate elasticity is low for most and high for the wealthy, and this difference is essential for banks and policymakers.

Elasticity also varies over time due to technological changes and balance sheets. The New York Fed indicates that “flightiness”—the speed at which deposits can leave—surged during the era of ample reserves and social media-enhanced runs. Greater flightiness makes banks more sensitive to policy changes, even if posted deposit rates lag. However, flightiness is not the same as sensitivity to offered yields. A crowd may flee on rumor but might ignore a gradual increase in advertised APYs. Banks study the economics of pass-through: each month, deposit rates move by about half the change in the fed funds rate, only closing a small part of the gap to their long-term levels. This explains why total deposit costs adjust, but not as swiftly as market rates, and why spreads widen during tightening cycles.

Why Iceland’s lesson travels—and where it doesn’t

Iceland is a great place to study deposit behavior. Digital banking is everyday; instant payments have been the norm for 20 years; transfers between similar risk accounts are just a tap away. If people still do not switch in such an easy environment, then inertia isn't solely about technology. It also involves attention, social norms, and the perception of small stakes by many households. Iceland’s income distribution and social safety net help clarify this trend. The country has a high GDP per capita in PPP terms, a low Gini coefficient near 0.25, and a low relative poverty rate. Incomes are higher and buffers thicker, making small yield gaps feel less pressing. This can lessen the perceived benefit of pursuing an additional percentage point on a few months’ cash. The same factors would apply in other high-income, high-coverage scenarios. Elasticity partly reflects a sense of need.

However, we must tread carefully. Social insurance policies, deposit protection, and market structures vary across countries. In the EU and EEA, standardized deposit insurance of €100,000 per depositor per bank lowers perceived risk and may dampen urgency to diversify. Meanwhile, 2023 showed that uninsured portions and balance-sheet losses can still prompt outflows. U.S. banks accessed emergency facilities; outflows slowed; insured deposits increased while high-risk funding diminished. This combination of stability and selective sensitivity warns against simple assumptions. Iceland demonstrates that, even in a small, digitized market, the average saver's deposit rate elasticity is low. In larger systems with more competition and marketing, elasticity may be higher at the margins. Yet the main behavior—inaction by many and action by the wealthy and financially savvy—continues to appear.

Policy for educators, administrators, and regulators

Education should come first. Suppose low deposit rate elasticity stems from scarce attention and complex mental math. In that case, basic, classroom-ready tools can influence behavior without being paternalistic. Show students how a one-point spread compounds on a simple emergency fund. Use real national averages from official surveys to ground the calculations. Then teach a two-step method: keep three months of spending in an insured, easy-access account that offers a competitive rate; transfer the rest to a term product with no withdrawal penalties or to a regulated money market fund. Evidence from mortgage markets suggests that people grasp rate changes when price tags adjust daily. We can apply that clarity in financial education by making deposit trade-offs concrete in terms of time and money rather than in basis points. The goal is not just to chase yield but to focus on defaults.

Administrators in higher education and school systems can help shape the market. Many already help staff set up retirement defaults. They should do the same for liquid savings: team up with banks or credit unions to automatically transfer payroll funds above a certain amount into insured, high-yield accounts, with an opt-out option available at any time. Require clear quarterly statements that compare the account’s APY with a simple national index. Display the benchmark on intranets so staff can quickly see if they are missing out on interest. Presented as a consumer-protection measure rather than product promotion, such defaults honor individual choice while increasing the perceived cost of ignoring good options. Since elasticity is highest among the wealthier and more financially informed staff, transparency can also promote equity by closing the information gap, hurting everyone else.

Regulators can take additional steps. First, standardize and publish a national “Retail Deposit Index,” similar to the mortgage PMMS, for banks to use in their disclosures. Second, mandate a single-screen comparison in mobile apps showing “Your APY vs. market index; estimated euros lost this quarter with no change.” Third, encourage or require automatic “rate parity” transfers within the same bank, moving idle balances from non-interest checking accounts to an interest-bearing savings account unless the customer opts out. The Iceland case illustrates that switching frictions within the same institution are already nearly nonexistent; the real issue is making the benefits clear. Where safety nets are strong and incomes high, clarity is essential. A slight nudge can convert stagnant balances into active ones, increasing the measured deposit rate elasticity without sacrificing stability.

Bank supervisors should monitor both flightiness and price pass-through. In 2023, deposit runs increased due to technological and social media developments; the Fed’s Bank Term Funding Program maintained credit flow; outflows slowed; and insured deposits grew. But none of this guaranteed that households received a fair share of the higher rates. Tracking liquidity risk is not the same as ensuring consumer pass-through. A system may be liquid, yet the average saver still under-earns by hundreds each year. Building on industry research, examiners can include deposit beta measurements by product and customer group in routine assessments. The goal is not to limit spreads but to make elasticity visible, comparable, and more responsive to competition over time.

Anticipating the critiques

One common critique argues that low deposit rate elasticity makes sense. Time is scarce, spreads are small, and switching costs exist. All true, but the Iceland data come from a context where switching is immediate, products are equivalent, and balances are significant. The wealthiest 10% still leave substantial sums unclaimed. This suggests that attention, not just costs, is the dominant factor. Another critique suggests that increasing elasticity could destabilize funding. The events of 2023 show both sides: flightiness rose, but policy measures and lender resources contained the effects. We can design nudges that increase price responsiveness without causing runs, especially for transfers within banks and insured balances. A third critique states that deposit markets are competitive; the best rates are easy to find. Yet the same data reveals that most savers do not search, and banks price accordingly. Disclosures that highlight the gap on each statement can shift the balance towards fairer pass-through.

A final concern is that Iceland is too small and unique. While it is indeed small, it has a distinctive social model. But that emphasizes the point: if even there—where frictions are minimal and trust is high—the average household does not respond to price incentives for safe, liquid deposits, sluggish pass-through is a general behavioral reality, not an anomaly. Differences in income, welfare coverage, and market concentration will affect the level of deposit rate elasticity. However, they will not change the pattern where wealthy and financially literate individuals drive the total, while most others remain passive. Policy should engage with people as they are: inattentive, busy, and risk-averse. Build reminders into products. Make the default option smart. Treat elasticity as an outcome that the system can improve, rather than a fixed trait of savers.

We began with one statistic: a one-point spread results in only a 0.1-point shift for the average household. This fact changes how we view the flow of higher policy rates to household cash. Mortgages and markets adjust rapidly; deposits wait for attention, which is scarce. The outcome is an unnoticed burden on savers and a failure in macro policy. Increasing deposit rate elasticity does not require massive changes. It requires making the cost of inattention clear and making switching easier. Educators can instill these habits with straightforward classroom principles. Administrators can create fair defaults. Regulators can ensure transparency and support intra-bank transfers. Banks can compete on clear benchmarks rather than flashy offers. If we align the system with actual human behavior rather than model assumptions, we can improve the weakest link in monetary transmission. When the next rate cycle arrives, households won’t have to chase the market. The market will come to them.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Bank Policy Institute. (2024, January 29). Deposit and interest rate risk: Some simple but surprising results.

Brookings Institution. (2024, October 3). Why have mortgage rates fallen, and where are they headed?

Drechsler, I., Savov, A., & Schnabl, P. (2017). The deposits channel of monetary policy. NBER Working Paper (revised).

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). (2023, Q2). Quarterly Banking Profile.

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). (2025, Q1). Quarterly Banking Profile — Data tables.

FREDDIE MAC. Primary Mortgage Market Survey (PMMS). Accessed 2025.

Glancy, D., et al. (2024). The 2023 banking turmoil and the Bank Term Funding Program. FEDS Working Paper.

Liberty Street Economics (New York Fed). (2025, July 10). The rise in deposit flightiness and its implications for financial stability.

OECD. (2025). Government at a Glance 2025: Iceland — Basic statistics of Iceland (2024).

RMA Journal. (2024, Jan–Feb). The increasing importance of understanding deposit betas.

VoxEU/CEPR — Cirelli, F., & Ólafsson, A. (2025, October 24). Households’ inaction in the deposit market.