Pecking Order Financing Beats Rate Tweaks: Why Cash Buffers, Not 25 bps, Move Investment

Input

Modified

Small rate tweaks rarely change investment Firms follow pecking order financing—cash first, then debt, equity last Targeted credit tools and skills policy move capex more than blanket cuts

Euro-area firms sent a clear message this autumn. Only 17% applied for a bank loan in the third quarter of 2025. Among those that did not apply, 55% said they had enough internal funds to cover their plans. This fact should change how we discuss monetary policy and business investment. Small, marginal rate changes make headlines, but they are not what most firms consider when they approve a project. They first look at their available cash, then at trusted lines of credit. This is the crucial concept of pecking order financing in action. That’s why a 25-basis-point cut rarely spurs investment unless a firm is already seeking new funds. If we want to see more real investment—like machines, software, and training—we should move away from focusing solely on the policy rate. Instead, we should design policy around how firms actually finance their operations.

The rate-cut fallacy and pecking order financing

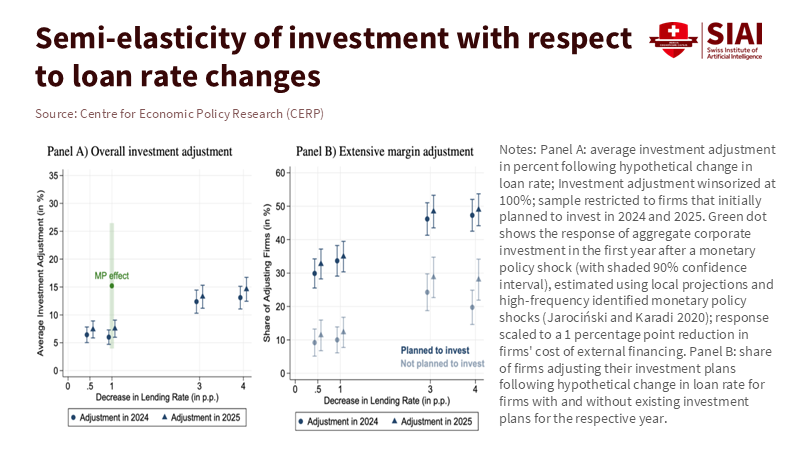

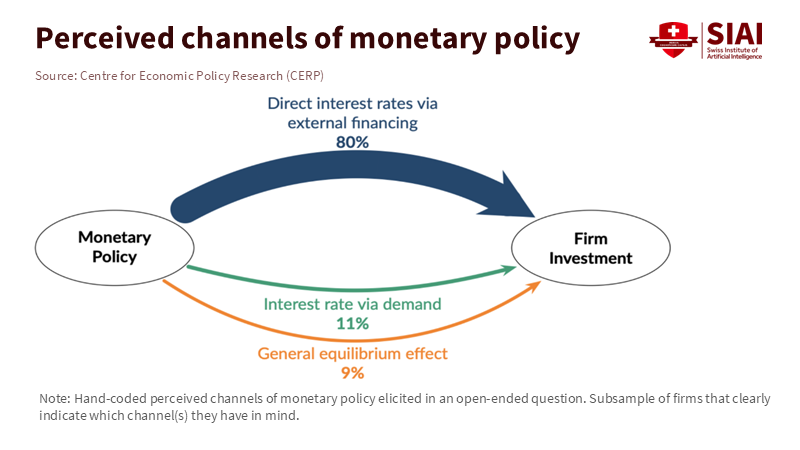

The current debate still treats investment as if a firm’s capital budget only responds to the policy rate. However, recent firm-level evidence shows that investment has a semi-elasticity of about 7 with respect to loan rates. This means that a full percentage-point increase in borrowing costs reduces planned investment by roughly 7%. A 25-basis-point move implies a decrease of about 1–2%. For many managers, this small percentage falls within the normal range of forecasting error and project risk. The same study reveals that when managers are asked why they do not adjust their plans, they cite cash buffers and a lack of projects that meet their internal standards, rather than recent rate changes. This should challenge the idea that small, frequent changes in policy rates have significant power. It's the internal thresholds and liquidity that firms base their investment decisions on, not the latest headline rate.

Another factor limiting rate changes is “sticky” hurdle rates. In thousands of corporate discussions, nominal discount rates used in capital budgeting change slowly and often do not adjust in line with expected inflation or the cost of capital. This rigidity weakens the impact of small policy changes. New survey research also finds that CFOs raise their hurdle rates by an average of 6–7 percentage points above the firm’s weighted average cost of capital—so they can gain bargaining power and filter out noise. A project that meets this high standard is unlikely to change in response to a quarter-point shift in the policy rate. Simply put, firms base their investment decisions on internal thresholds and liquidity, not on the latest headline rate.

Cash buffers beat cheap credit in pecking order financing

Understanding the pecking order financing hierarchy is crucial. Firms prefer to use internal funds first, then debt, and only then equity. This intuition—where external money is seen as costly—remains a powerful guide to real behavior. Two current data points illustrate this. First, euro-area firms have been bypassing the loan desk because they have enough internal liquidity; in Q3 2025, “sufficient internal funds” was the main reason for not applying for a loan. Second, U.S. nonfinancial corporations held around $2.19 trillion in cash and checkable deposits in Q2 2025 alone. Such large cash reserves make small changes in loan pricing seem minor for everyday capital expenditures. When liquidity covers most of the following year’s program, a firm won’t rush to borrow just because credit is 25 basis points cheaper. They will invest when projects meet their internal standards and their cash buffer remains safe. This understanding of the pecking order financing hierarchy can guide policymakers in designing more effective policies.

Significantly, recent rate cuts in Europe have affected average corporate loan rates, but the effects are slow and uneven. In August 2025, average rates on new corporate loans in the euro area were just over 3%, down from earlier peaks. Even so, many firms rely on cash flow and retained earnings because internal funds are faster, simpler, and under their control. The pecking order explains this choice. Internal funds avoid disclosure costs, renegotiation risks, and lender covenants. Firms choose debt next because it dilutes control less than equity. They view equity as a last resort due to ongoing concerns about adverse selection. Monetary policy can influence the price of debt, but it does not affect the availability of internal funds.

While loan pricing matters, it is most relevant when a firm is ready to enter the market, such as refinancing, funding a big project, or rolling debt. In the typical quarter, the average firm funds its projects from the top of the ladder. That is why changes in internal liquidity—from cash flow shocks, tax changes, late receivables, or fiscal investment incentives—often impact investment more than small, frequent rate changes. Policymakers who overlook this hierarchy will pursue outcomes with the wrong tools and may question why capital expenditures remain stagnant.

Heterogeneous credit supply and why targeted tools beat blunt cuts

Loan availability varies widely by firm age, leverage, sector, and country. Large, rated firms can issue bonds or access revolving credit easily. In contrast, younger and highly leveraged firms face tighter constraints and more volatile pricing. Manufacturing and durable goods producers usually respond more to policy shocks than service industries, and their reactions last longer. This variation means that the exact 25-basis-point change sends different signals across different balance sheets. Averages mask the real situation. This results in a transmission mechanism whose effectiveness depends on who needs external funding today and the banks that serve them.

The past few years have also highlighted the importance of the specific tools used. The ECB's targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTROs) significantly lowered bank funding costs—sometimes to as low as −1%—and linked that relief to lending volumes. When these operations ended and banks repaid over €2 trillion, the structure of liabilities changed, as did the incentives to extend loans. New research on “dual-rate” designs shows how targeted rates can influence bank risk-taking and lending to firms more effectively than broad rate cuts. The policy lesson is clear: if the goal is to direct bank credit to businesses that genuinely need it, targeted approaches through banks are more effective than minor changes to a headline rate.

Cross-country data reinforce this point. The transmission from policy rates to loan rates varied across the euro area from 2022 to 2024, with a slower rate of pass-through compared to the mid-2000s cycle. Countries with more variable-rate corporate loans transmit changes faster, while those with different banking structures see slower responses. Add in weak demand and cautious banks, and you get low net lending to firms even as the policy stance eases. In such circumstances, a broad rate cut is an inefficient tool. A targeted mix—credit operations with conditions, sector-specific guarantees, and public co-investment in hard-to-collateralize projects—will reach constrained firms more swiftly.

Policy for the fundamental constraint: liquidity, skills, and selective credit

If pecking-order financing is the norm, the real investment bottleneck often lies in the firm's liquidity, not the interest rate on a bank loan. This shifts the focus for finance ministries. The primary lever is to stabilize internal cash flow at decision-making moments. Faster settlement of public invoices, upfront investment allowances, and accelerated depreciation for equipment and software can all strengthen cash buffers at the top of the hierarchy. For development banks, bridging the unsecured middle means offering guarantees and revenue-based finance for firms with solid growth potential but insufficient collateral. For central banks, the takeaway is to move away from minor, frequent rate adjustments and focus on contingent credit tools. This includes keeping targeted operations ready to activate when market risks tighten, funding certain firms while leaving others with plenty of cash.

Education policy plays a vital role in this macro-financial narrative because firms now cite the availability of skilled labor as their most significant constraint, not interest costs. In a recent euro-area survey, 63% of firms pointed to skill shortages as a substantial limitation on production. This far exceeds the share that mentions loan costs, highlighting where additional funding should go to encourage private investment. When skilled workers are scarce, projects often stall at internal hurdles, even when money is affordable. This dynamic complements pecking order financing: the internal standard drops when teams have the skills to execute. For education ministries and universities, the message is to focus on short, modular programs tied to clear job roles in areas like energy retrofits, AI adoption, cybersecurity, and advanced manufacturing.

School leaders and training providers should now prioritize co-designing micro-credentials with local firms and tracking job placement within a quarter of program completion. For those managing tertiary education systems, the goal should be to simplify credit transfer and recognition across institutions so working learners can quickly build up their skills. For policymakers, any intervention should be evaluated based on whether it increases internal liquidity or reduces the non-price barriers that prevent viable projects from moving forward. Following the pecking order financing framework can help: enhance retained earnings capacity through steady cash flow, streamline debt with guarantees, and reserve equity for the few cases where speed and scale justify dilution. This approach aligns how firms actually finance operations with how policy aims to assist, making it the most likely path to spur investment now.

The headline rate will always attract attention. However, firms usually make investments quietly—by checking their internal funds, assessing projects against sticky benchmarks, and only then approaching banks. In Q3 2025, a majority of euro-area firms didn’t even apply for a loan because their own cash was sufficient. This indicates what truly matters in the economy. To boost private investment, we should prioritize building cash buffers, targeting credit where constraints exist, and developing the skills needed to get projects underway. This leads to a more genuine transmission mechanism and a faster impact. Monetary policy should maintain its targeted tools, fiscal policy should support internal liquidity at crucial times, and education policy should enhance the supply of essential skills. By working together on these fronts, pecking-order financing can shift from an obstacle to a pathway that facilitates investment in the real economy.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Bank of Finland. (2024). Impact of ECB’s policy rate changes on corporate loan rates varies strongly across countries. Bof Bulletin, 11/2024.

Bank of Finland. (2025). Variable rate corporate loans strengthen transmission of monetary policy. Bof Bulletin, 10/01/2025.

Banque de France / ECB. (2025). Euro area bank interest rate statistics: April 2025. Press release PDF.

Bundesbank. (2025). Monetary policy and banking business—Monthly Report, August 2025.

ECB. (2024, updated 2024-09-13). What are targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTROs)? Explainer.

ECB. (2025). Economic Bulletin box: TLTRO III phase-out and bank lending conditions.

ECB. (2025). Survey on the Access to Finance of Enterprises in the euro area—Third quarter of 2025.

IMF. (2024). ECB Monetary Policy Passthrough to Bank Interest Rates—Selected Issues.

Myers, S. C. (2001). Capital Structure. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 15(2), 81–102.

Myers, S. C., & Majluf, N. S. (1984). Corporate financing and investment decisions when firms have information that investors do not have. NBER Working Paper 1396.

St. Louis Fed (FRED). (2025). Nonfinancial Corporate Business; Checkable Deposits and Currency; Asset, Level (BOGZ1FL103020005Q). Q2 2025.

Vilerts, K., Anyfantaki, S., Benkovskis, K., et al. (2025). Details matter: How loan pricing affects monetary policy transmission in the euro area. VoxEU/CEPR Column.

Best, L., Born, B., & Menkhoff, M. (2025). The Impact of Interest: Firms’ Investment Sensitivity to Interest Rates. CESifo Working Paper 12167 (SSRN).

Durante, E., Ferrando, A., & Vermeulen, P. (2022). Monetary policy, investment and firm heterogeneity. European Economic Review, 148.

Fukui, M., Huber, K., et al. (2024). Sticky Discount Rates. NBER Working Paper 32238.

Hurdle Rate Buffers and Bargaining Power in Asset Development. (2025). SSRN Working Paper.

European Central Bank. (2025). Press release: SAFE—Lending conditions tightened marginally, needs and availability broadly unchanged (27 Oct 2025).