AI Labor Displacement and Productivity: Why the Jobs Apocalypse Isn't Here

Published

Modified

AI boosts task productivity, especially for novices AI labor displacement is real but small and uneven so far Protect entry-level pathways and buy for augmentation, not replacement

Let's start with a straightforward fact. U.S. labor productivity increased by 2.3% in 2024. This improvement comes after several years of weakness, with retail rising by 4.6% and wholesale by 1.8%. However, the feared rise in unemployment linked to generative AI has not materialized. Recent evidence supports this. A joint analysis by the Yale Budget Lab and Brookings, released this week, finds no significant overall impact of AI on jobs since the debut of ChatGPT in 2022. The labor market appears stable rather than in crisis. AI is spreading, but the so-called "AI jobs apocalypse" has not arrived. This doesn't mean there is no risk. Exposure is high in wealthy economies, and AI labor displacement will likely increase as adoption continues. Currently, we are witnessing modest productivity gains in some sectors, a slow spread in others, and localized displacement. This pattern is familiar; we experienced it with computers. We must develop policies based on this pattern: prepare rather than panic, emphasizing the urgency of preparing for the potential labor displacement that AI may cause.

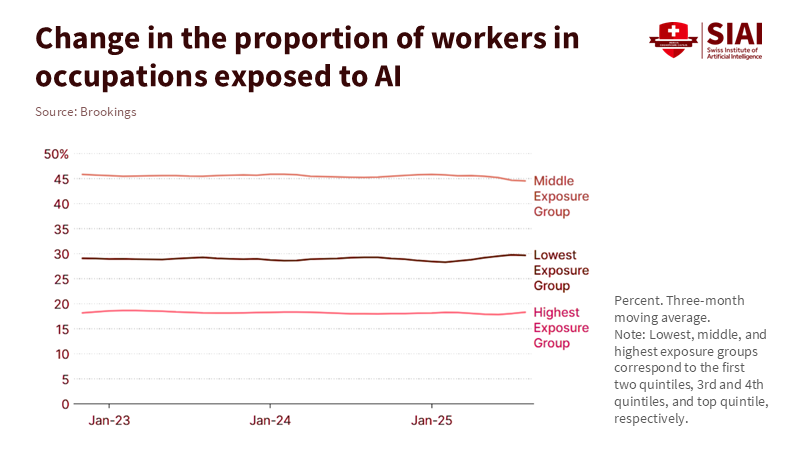

AI labor displacement is a real issue, but it is slow, uneven, and concentrated in specific areas

Let's look at adoption. Businesses are rapidly using AI, but from a low starting point and with clear divisions. In 2024, only 13.5% of EU companies had adopted AI, whereas the rate was 44% in the information and communication services sector. More than two-thirds of ICT firms in Nordic countries were already using it. Larger companies utilize AI much more than smaller ones. Areas like Brussels and Vienna progress rapidly, while others lag. This suggests we will first see AI labor displacement in knowledge-intensive services and large organizations with strong digital capabilities. Most smaller companies are still testing AI rather than transforming their operations. This diffusion explains why the overall job effects remain limited, even as specific teams adjust their workflows. It also indicates that displacement risk will come in waves, not all at once. Tracking these differences by sector, company size, and region is more important than monitoring a single national unemployment rate.

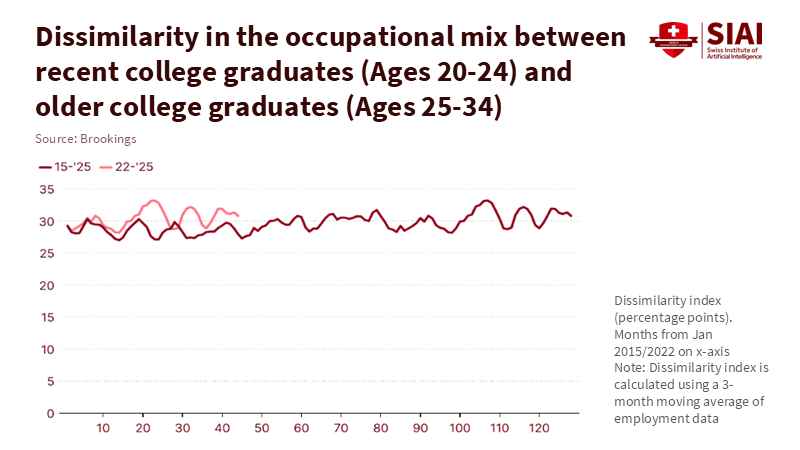

Evidence regarding jobs supports this narrative. The new Yale-Brookings report indicates that no widespread employment disruption has been linked to generative AI so far. This aligns with recent private reports indicating increased layoffs and weak hiring plans for 2025, with only a small portion explicitly tied to AI. Challenger, Gray & Christmas reported 17,375 job cuts attributed to AI through September. While significant for those affected, this figure is small compared to the nearly one million planned reductions for the year. The key takeaway is that while AI does have some impact on labor, the job loss directly caused by AI remains a small fraction of total turnover. Meanwhile, some companies report "technological updates" as a reason to slow or freeze entry-level hiring, which serves as an early warning for junior positions. For educators and policymakers, this means creating pathways for entry-level jobs before these roles become too scarce.

Studies on productivity provide additional context. Evidence shows gains at the task level, especially for less experienced workers. In a study involving 5,000 customer support agents, generative AI assistance increased the number of issues resolved per hour by approximately 14% on average, and by more than 30% for agents with less experience. In randomized trials involving professional writing, ChatGPT reduced the time spent by approximately 40% and improved the quality of the output. These increases are not yet observable across the entire economy, but they are real. They highlight how AI labor displacement can occur alongside skill improvement. The same tools that threaten entry-level roles can help junior workers advance, creating both opportunities and challenges. Companies may hire fewer inexperienced employees if software narrows the skills gap while raising the baseline for those they do hire. Education systems must address this intersection where entry-level tasks, learning, and tools now overlap, fostering a sense of optimism about the potential for skill improvement in the workforce.

History offers valuable lessons: computers, worker groups, and gradual changes

We have seen this story before. Computerization changed tasks over decades, rather than months. It replaced routine work while enhancing problem-solving and interpersonal tasks. This led to job polarization, with growth at the high and low ends while pressure built in the middle. Older workers in routine jobs faced shorter careers and wage cuts if they were unable to retrain quickly. This is the pattern to watch with generative AI. The range of tasks at risk is wider than with spreadsheets, but the timeline is similar. Occupations change first, worker groups adapt next, and overall employment rates adjust last. This is why AI labor displacement today involves task reassignments, hiring freezes, and role redesigns, rather than mass layoffs across the economy. The impact will be felt personally well before it appears in national data.

This analogy also helps clarify a common misunderstanding. Many jobs involve a variety of tasks. Chatbots can handle translation, summarization, or produce first drafts. However, they cannot carry equipment, supervise children, calm distressed patients, or fix a boiler. The IMF estimates that about 40% of jobs worldwide are vulnerable to AI, with around 60% at risk in advanced economies, mainly due to the prevalence of white-collar cognitive work. Exposure does not equal replacement. For manual or in-person service jobs, exposure is lower. In cognitively demanding office roles, exposure is higher, but the potential for complementarity is also greater. As with computers, the long-term concern is not a jobless future but a more unequal one if we do not manage the transition effectively.

From hype to policy: focus on productivity while avoiding exclusion in AI labor displacement

A realistic approach begins with careful measurement. We should track AI adoption by sector and company size, rather than relying solely on total unemployment figures. Business surveys and procurement reports can help map tool usage and track changes in tasks. Education ministries and universities should publish annual reports on "entry tasks" in fields at risk, such as translation, routine legal drafting, and customer support, so that curricula can be adjusted in advance to meet these needs. Governments can encourage progress by funding pilot programs that combine AI with redesigned workflows, collecting results, and expanding only where productivity and quality improve. At each step, document what tools changed, what tasks shifted, and which skills proved most important. This approach connects adoption to outcomes rather than following trends or vague promises, providing reassurance about the potential solutions to AI labor displacement.

Next, we must protect the entry path. A clear sign is the pressure on internships and junior jobs in roles that are highly exposed to AI. Policies should aim to make entry-level positions easier to fill and more enriching in terms of learning opportunities. Wage subsidies tied to verified training plans can encourage firms to replace novice roles with AI. Public funding for "first rung" apprenticeships in marketing, support, and operations can combine tool training with essential human skills, such as client interaction, defining problems, and troubleshooting. Universities can reduce traditional teaching time in favor of hands-on labs that utilize AI to simulate real-world processes, while ensuring that human feedback remains essential and integral to the learning process. The goal is straightforward: help beginners advance faster than the job market shifts away from them.

Third, focus on enhancing AI implementations. Procurement can require benchmarks that prioritize human involvement, not just cost reductions. A school district using AI tutors should evaluate whether teachers spend less time grading and more time coaching. A hospital using ambient scribing should check for reduced burnout and fewer documentation errors. A city hall employing co-pilots should monitor processing times and appeal rates. If a use case adds capability and reduces mistakes, keep it. If it only takes away learning opportunities for early-career workers, redesign it. Link public funding and approvals to these evaluations. This way, we can steer AI labor displacement toward creating better jobs instead of weaker ones.

A five-year plan to turn displacement into better work

Start with educational institutions. Teach task-related skills—what AI does well, its limitations, and how to connect tasks effectively. Teach students to critique their own work rather than produce it. In writing courses, students are required to submit drafts that include the original prompt, the edited output, and a revised version with notes explaining changes in structure, evidence, and tone. In data courses, evaluate error detection and data sourcing. Highlight "AI labor displacement" in clear terms for learners: tools can take over tasks, but people must remain accountable.

Shift teachers' roles toward coaching. Utilize co-pilots to create rubrics and updates for parents; redirect freed-up time to provide small-group feedback and support for social-emotional needs. Track the allocation of this time. If a school saves ten teacher hours a week, report on how that time is used and any changes in outcomes. Pair these adjustments with micro-internships that give students supervised experience in prompt design, quality assurance, and workflow development. This creates a pathway from the classroom to the first job as novice tasks become less secure.

For administrators, revise procurement processes. Start with four steps: define the baseline for tasks, establish two main metrics (quality and time), conduct a limited trial with human quality assurance, and only scale up if both metrics are met for low-income or novice users. Require suppliers to provide records that can be audited to demonstrate where human value was added. Publish concise reports, similar to clinical trial results, so other districts or organizations can replicate successful methods. This governance process is intentionally tedious. It's essential for protecting livelihoods and public funds.

For policymakers, consider combining portable benefits with wage insurance for mid-career shifts and expedited certification for those who can learn new tools but lack formal degrees. Increase public investment in high-performance computing for universities and vocational centers, allowing learners to engage with real models instead of mere demonstrations. Support an AI work observatory to identify and monitor the initial tasks changing within companies. Use this data to update training subsidies each year. Connect these updates to areas where AI labor displacement is evident and where complementary human skills—like client care, safety monitoring, and frontline problem-solving—create value.

Finally, be honest about the risks. People today are losing jobs to AI in specific areas. Journalists, illustrators, editors, and voice actors have experiences to share and bills to pay. These individuals deserve focused assistance, including legal protection for training data and voices, transition grants, and public buyer standards that prevent a decline in quality. An equitable transition acknowledges the pain and builds pathways forward rather than dismissing concerns with averages.

The most substantial evidence points in two directions at once. On the one hand, there is no visible macro jobs crisis in the data. Productivity is gradually improving in expected sectors, such as retail and wholesale, as well as certain parts of the services industry. AI is also producing measurable gains in real-world workplaces, particularly for newcomers. On the other hand, adoption gaps are widening across sectors, company sizes, and regions, and AI labor displacement is altering entry-level tasks. This situation should guide our actions. Use this calm period to prepare. Keep newcomers engaged with redesigned pathways into the job market. Prioritize acquisitions and regulations that focus on enhancement and quality, rather than just cost. Carefully measure changes and make that information public. If we do this, we can manage the feared shift and create a smoother transition. While we cannot prevent every job loss, we can help avoid a weakened middle class and damage to entry-level positions. The productivity increase discussed at the beginning—a steady yet modest rise—can illustrate a labor market that adapts, learns, and becomes more capable, rather than more fragile. That is the type of progress we should work to protect.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Acemoglu, D., & Autor, D. (2011). Skills, Tasks and Technologies: Implications for Employment and Earnings. (Working paper). Retrieved October 3, 2025.

Autor, D. H., Levy, F., & Murnane, R. J. (2003). The Skill Content of Recent Technological Change: An Empirical Exploration. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118(4), 1279–1333.

Autor, D. H., & Dorn, D. (2013). The Growth of Low-Skill Service Jobs and the Polarization of the U.S. Labor Market. American Economic Review, 103(5), 1553–1597.

BLS (2025, Feb 12). Productivity up 2.3 percent in 2024. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Retrieved October 3, 2025.

Brynjolfsson, E., Li, D., & Raymond, L. (2023). Generative AI at Work. NBER Working Paper No. 31161. Retrieved October 3, 2025.

Challenger, Gray & Christmas (2025, Oct 2). September Job Cuts Fall 37% From August; YTD Total Highest Since 2020, Lowest YTD Hiring Since 2009 (and September 2025 PDF). Retrieved October 3, 2025.

Georgieva, K. (2024, Jan 14). AI Will Transform the Global Economy. Let's Make Sure It Benefits Humanity. IMFBlog. Retrieved October 3, 2025.

IMF Staff (Cazzaniga et al.) (2024). Gen-AI: Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Work (SDN/2024/001). International Monetary Fund. Retrieved October 3, 2025.

Noy, S., & Zhang, W. (2023). Experimental Evidence on the Productivity Effects of Generative Artificial Intelligence. Science, 381(6654), eadh2586 and working paper versions. Retrieved October 3, 2025.

OECD (2025). Emerging divides in the transition to artificial intelligence (Report). Paris: OECD Publishing. Retrieved October 3, 2025.

Yale Budget Lab & Brookings (2025, Oct 1–2). Evaluating the Impact of AI on the Labor Market: Current State of Affairs; Brookings article New data show no AI jobs apocalypse—for now. Retrieved October 3, 2025.

The Guardian (2025, May 31). 'One day I overheard my boss saying: just put it in ChatGPT': the workers who lost their jobs to AI. Retrieved October 3, 2025.

Comment