Names, Signals, and Fairness: Designing Blindness That Actually Works

Input

Modified

Treat blind hiring policy as a targeted tool, not a cure-all Recent pilots show anonymity widens access while quality holds steady Use a tiered process—Stage-1 blind scoring, controlled unblinding, and outcome audits—to balance equity and excellence

A single change influenced opportunities: in Helsinki’s public-sector pilot, anonymous applications increased interview callbacks for foreign-sounding names by about 5% and boosted hires, without affecting job tenure or wages. This isn't a significant revolution. However, in large systems, a five-point increase can reshape who gets training, who joins labs, and who moves up the ladder. The takeaway isn’t that a blind hiring policy automatically eliminates bias. It’s that design choices determine if anonymity opens doors or shuts them. In higher education, where name recognition and institutional prestige still sway opinions, anonymity should be seen as a focused tool rather than an absolute principle. When used effectively, it reduces noise and status-related biases. When misused, it can eliminate valuable signals and may even have adverse effects. The challenge now is to create anonymity that maintains quality signals while removing misleading proxies.

Why the debate on blind hiring policy needs reframing

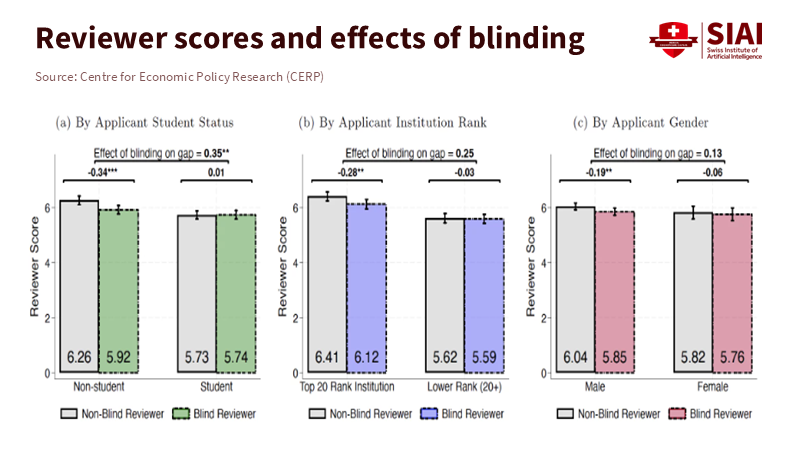

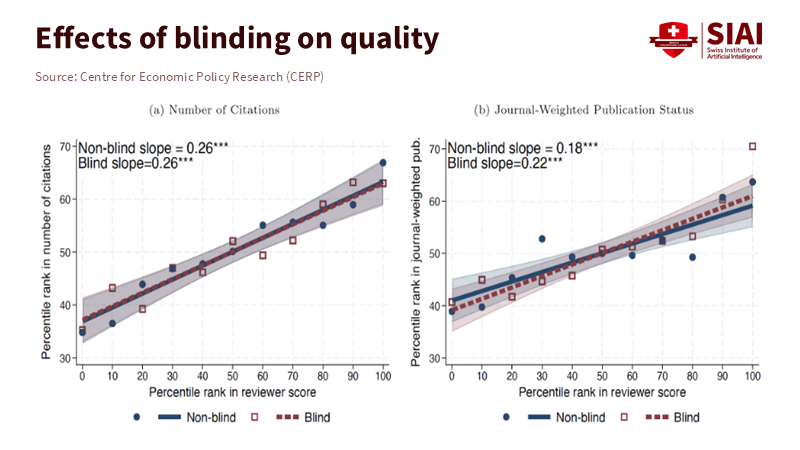

The traditional debate is simple: hide names to prevent bias or keep them because names contain valuable information. Both positions have merit, but they are incomplete. Academic reviews provide clear evidence: a recent randomized study presented at a major international conference found that concealing authors' names reduced the acceptance gap between students and senior researchers. It also reduced disparities in institutional rank without losing predictive power for later citations and publications. This means that the content was strong enough on its own. However, the same research shows mixed results in different settings. In some cases, anonymity can dampen unfair status indicators. In others, it can silence real signals we still need. The key question is no longer “blind or not.” It is “what to blind, when, and for whom,” based on the specific problem we want to address.

This new perspective is essential because educational selection methods are evolving rapidly. Digital platforms, pooled reviews, and AI-assisted screening speed up evaluations. As the process accelerates, shortcuts become more common. Prestige can serve as an easy option. Anonymity can disrupt that shortcut, but only if it’s combined with better, structured indicators of quality. The Finnish pilot shows this clearly: anonymity improved interview chances and hires for foreign-named applicants. Importantly, downstream metrics such as wages and job duration remained stable, indicating that quality was maintained. Yet there are also cautionary examples. A field trial in France by the public employment service found that anonymized résumés in a voluntary program led to fewer interviews and hires for minority candidates—likely because the firms that agreed to participate were already trying to hire fairly and lost valuable tools that helped them do so. The design and context—not simply the label “blind”—shaped the results.

What does the latest evidence actually say about blind hiring policy

Between 2023 and 2025, three key research trends will guide policy. First, in hiring, recent pilots demonstrate that anonymity can improve access for minority groups in early stages without sacrificing quality. Helsinki’s randomized rollout increased the chances of interviews for applicants with foreign names and led to more hires; the city then made anonymity an optional tool for managers. A significant Dutch pilot from 2016 to 2017, examined in a 2024 peer-reviewed study, also revealed that minority applicants were more likely to receive interview invitations after the introduction of anonymity. These effects are not universal. They depend on the presence of prestige and name-based shortcuts, as well as on the structure of the evaluation criteria.

Second, in academic evaluation, evidence shows double-anonymized processes may improve inclusion by gender or affiliation, but their effects vary by context. Reviews and studies from 2022 onward found that double-blind peer review closed some gaps, such as gender ratios, but left other disparities. An editorial analysis in 2024 noted that double-anonymization alone did not enhance geographic diversity, whereas triple-anonymization showed greater promise. A 2025 experiment confirmed that blinding preserved quality assessment while shifting representation toward students and non-top-20 institutions. In summary, anonymity can alter selection patterns without diminishing quality, but its field-specific impact depends on which information is hidden or revealed.

Third, in education assessment, anonymized grading can produce small yet significant advantages for underrepresented groups. A 2025 study in Economics Letters found that a university-wide switch to anonymous grading improved female students’ grades by around 0.035 standard deviations compared to their male counterparts. The effects were more pronounced in smaller classes and male-dominated departments. Supporting work from 2024 shows that objective rubrics can reduce biases related to migration among pre-service teachers in experimental contexts. Although these results are modest, they reinforce an essential design principle: anonymity is most effective when combined with clear, performance-based criteria. The question for universities and research organizations now is how to design blind-hiring policies that reflect these lessons.

A tiered blind hiring policy for universities and research

To move beyond the outdated 'blind versus not' discussion, higher education should adopt a tiered model. Start by concealing names and affiliations, using structured assessments focused on content, skills, and outputs. Rubrics should be based on demonstrable evidence—like coding samples or teaching videos—to limit prestige shortcuts and reward performance. This tiered approach leverages equity gains already proven in Helsinki and Dutch pilots: anonymity lifts underrepresented applicants at initial stages. The central argument is to use targeted, staged anonymity to maximize fairness without undermining quality.

Stage 2 should involve controlled “unblinding” after a shortlist has been created. At this stage, evaluators will see affiliations and credentials, but within precise limits. Panels must provide written justifications for any changes from Stage 1 rankings, citing relevant reasons related to the role (e.g., supervisory needs that weren’t evident in the blind materials). Here, brand and network information can be helpful to but must be documented and managed. Where appropriate, pair unblinding with structured reference checks that request concrete evidence linked to the rubrics rather than general praise. Universities should also conduct straightforward quarterly audits to determine if reversals from Stage 1 disproportionately affect candidates from non-elite institutions. If they do, adjust the rubric or require additional oversight. This feedback loop ensures that quality signals remain while minimizing the influence of status.

Stage 3 should focus on the outcomes after selection. If anonymity is practical, cohorts selected under the new system should perform at least as well regarding job-relevant outputs, such as course evaluations adjusted for response bias, completion of research milestones, grant productivity for faculty hires, and retention. In the Helsinki study, anonymity did not negatively impact wages or job duration; in the conference experiment, blind evaluations predicted subsequent citations and publications similarly to non-blind scores. Universities can adopt this approach through their own long-term assessments. The goal isn’t to achieve identical outcomes across groups but to ensure that performance does not decline when prestige cues are reduced.

Guardrails, counterarguments, and how to measure success

Critics raise two valid concerns. First, names and school brands provide essential information. In places like South Korea, school names reflect years of competitive exams and intense ranking. Employers often argue that this information correlates with workplace success. However, blind hiring there did not eliminate information; the 2019 law restricted unrelated questions, minimized nepotism, and encouraged companies to focus on job-relevant criteria. A 2023 survey reported by Korean media indicated that many applicants still view blind hiring as the fairest approach, and one well-known company noted a drop in nepotistic hires from hundreds to single digits after the reforms. These are rough indicators, not definitive proof, but they illustrate how policy can reshape norms. The better response to the argument that “brands signal information” is not to abandon anonymity; it's to replace brands with direct, job-relevant signals and then reintroduce personal identity later, within clear boundaries.

Second, some studies show adverse results. The French trial is an example where minority candidates performed worse with anonymized résumés. Policymakers should not ignore this but should strive to understand it. Two design choices likely contributed to this outcome: self-selection by companies already inclined toward fair hiring and the loss of resources those firms used to support minority candidates once identities were hidden. The solution is institutional: make Stage 1 anonymity the default in public institutions to reduce selection bias. Pair this with targeted prompts that capture strengths often overlooked due to anonymity—such as community leadership or non-linear career paths—without relying on identity cues. Allow job-relevant context statements within the blind materials. Then audit the results. If reversals in Stage 2 decrease representation without improving performance, change the rules. Quality should uphold equity, and equity should ensure that false signals do not go unchecked.

Measurement needs to be straightforward and effective. For each round, track three metrics: shortlisting rates, offers made, and performance benchmarks for the first year. Compare these metrics for cohorts evaluated under the new method to those from previous processes. Where possible, use randomized rollouts across departments and difference-in-differences analysis to isolate the effects. Support this with smaller, targeted studies: in grading, anonymous marking has improved outcomes for women in some university settings; in teacher education trials, objective rubrics have reduced judgment bias linked to migration background. None of these are silver bullets, but they are small, meaningful achievements that add up. When they do, we observe the same trend as in Helsinki and in the conference study: increased representation, with quality remaining constant.

From prestige shortcuts to performance signals

The way forward is neither naive blindness nor a surrender to brand power. It requires careful design. Start with Stage 1, an anonymity-focused stage focused on content and skills; progress to Stage 2, an unblinding stage with documented justifications; and conclude with Stage 3 audits assessing outcomes relevant to the job. In teaching and learning, parallel steps should be taken: pair anonymous grading with clear rubrics, and use moderation to standardize expectations across sections. In research selection, employ double-anonymized reviews where status cues are most prevalent, but also consider triple-anonymized processes or structured author-contribution forms if geographic or affiliation biases are evident. Avoid token fixes; instead, invest in the gradual efforts of rubric design, reviewer training, and feedback.

A five-point increase in interview chances may not seem significant at first glance. Yet, among thousands of candidates each year, it means hundreds more individuals from non-dominant groups will receive attention, and some will be hired—without compromising quality. Academic conferences reflect the same trends: blinding can expand who is given a platform while maintaining our ability to predict future impact. That is the balance we should strive for. Let’s incorporate it into policy. Universities, funding organizations, and school systems can test a tiered, blind-hiring policy during the upcoming admissions and hiring cycle, publish the results, and make improvements twice a year. The goal is straightforward: reduce reliance on prestige shortcuts, increase focus on performance signals, and promote fairer opportunities without forcing a choice between equity and excellence.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Behaghel, L., Crépon, B., & Le Barbanchon, T. (2014). Unintended effects of anonymous résumés (IZA DP 8517). IZA Institute of Labor Economics.

Blommaert, L., Coenders, M., & van Tubergen, F. (2024). The effects of and support for anonymous job application procedures: Evidence from a large-scale, multi-faceted study in the Netherlands. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies.

Gayet-Ageron, A., et al. (2024). Gender and geographical bias in the editorial decision process. PLOS ONE.

Ius Laboris / Yulchon LLC. (2019). South Korea – “Blind Hiring Act” now in force.

Jansson, J., & Tyrefors, B. (2025). The effect of an anonymous grading reform for male and female university students. Economics Letters, 248, 112241.

KoreajoongAng Daily. (2023, January 3). Turns out knowing little about a job applicant is less than ideal.

Lippens, L., et al. (2023). The state of hiring discrimination: A meta-analysis of correspondence experiments. European Economic Review.

Rinne, U. (2025). Anonymous job applications and hiring discrimination. IZA World of Labor.

Uchida, H. (2025, December 10). What hiding applicant names reveals about discrimination in evaluations. VoxEU/CEPR.

European Commission, DG Home. (n.d.). Helsinki pilot project: Anonymous recruitment—results summary.

Kanninen, O., Kiviholma, S., & Virkola, T. (2023/2025). Equity and efficiency in anti-discrimination policy: Evidence from an anonymous hiring pilot (SSRN Working Paper).

The World. (2019, July 17). South Korea’s new “blind hiring” law bans personal interview questions.

Cássia-Silva, C., et al. (2023). Overcoming the gender bias in ecology and evolution: Is double-anonymized peer review an effective pathway over time? PeerJ, 11, e15186.

Peter, S., et al. (2024). Objective criteria reduce judgmental bias on grading. Frontiers in Education.

Comment