Jobs, Not Productivity: How urban over-centralization broke the geography of work

Input

Modified

Capitals dominate because jobs concentrate, not because productivity lags elsewhere Move demand and decision rights to secondary cities to thicken labor markets Align education pipelines and public procurement to reward distributed hiring and retention

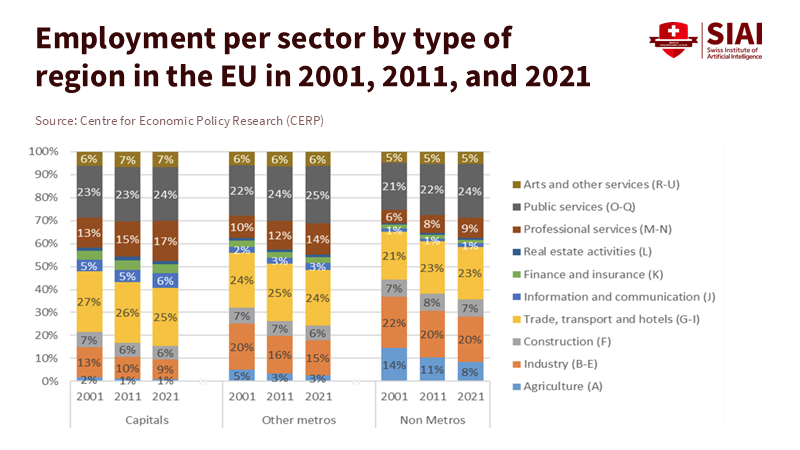

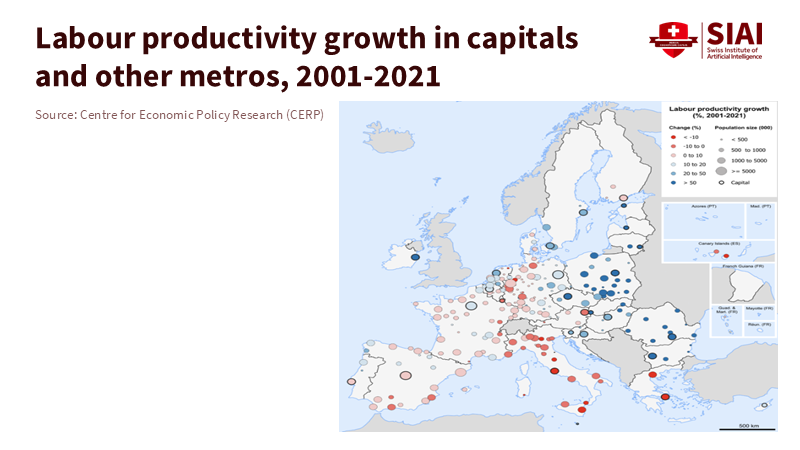

A single number illustrates the problem. In 2023, the Seoul Capital Area, which includes Seoul, Incheon, and Gyeonggi, was home to 50.7% of South Korea’s population and generated about 53% of its GDP. This means that more than half the nation’s jobs and output came from roughly an eighth of its land. The Lima metro area alone accounts for about 44% of Peru’s GDP. A recent 20-year study in the European Union shows that capital metro areas have outpaced other cities in productivity growth. Meanwhile, non-metro areas improved productivity but lost population and jobs. These trends are not isolated; they represent a pattern. Urban over-centralization gathers jobs and institutions in capital cities, not because suburbs and smaller towns have stopped producing, but because jobs, resources, and networks have shifted and continue to grow in these areas. If the output gap is not a productivity gap, we need to change our focus. The goal should be to spread sustainable, high-quality job opportunities rather than pushing generic productivity messages into areas that have already lost jobs.

Reframing urban over-centralization: the jobs engine, not a productivity myth

The main point is straightforward. Places that lag do not inherently lack productivity; instead, they offer fewer jobs. A recent analysis of metropolitan regions across the EU demonstrates that capital metro areas recorded the highest productivity growth from 2001 to 2021 and also posted significant job and population growth. Other metro areas trailed in both categories. Non-metro areas managed to increase productivity nearly as quickly as capitals, but their populations and job numbers stagnated or declined. When fewer workers participate, and payrolls shrink, per-capita income suffers regardless of how efficiently firms operate. In other words, the geography of urban over-centralization maps jobs, not talent. Policies aimed at fixing provinces’ so-called "efficiency deficits" ignore the real issue: too few career-track positions, too few anchor institutions, and too little market demand.

This pattern exists beyond Europe. In Korea, the capital region accounts for nearly 53% of GDP and similarly dominates population figures. Japan’s urban areas account for about three-quarters of the national GDP, with Tokyo alone accounting for more than a third of metropolitan growth in the 2000s. Latin American primary cities show even greater concentration: Mexico City generates around 18% of national GDP, and, as mentioned, Lima is close to 44%. These statistics do not suggest that residents in cities like Córdoba or Arequipa cannot contribute; they highlight that headquarters, high-level services, universities, government agencies, and supply-chain coordinators cluster together and drive the rest of the economy. When anchors move, jobs follow; when hiring increases, skills develop; and where skills gather, new firms emerge—again in the same location.

Evidence across regions: urban over-centralization from Brussels to Tokyo to Lima

New evidence from Europe is crucial because it shifts our understanding of the problem. If non-metropolitan areas can increase productivity almost as quickly as capitals but still lose ground, then the issue is a lack of job demand, not workers' or firms' abilities. The EU's analysis breaks down growth and shows that most productivity gains happened within sectors rather than through moving to better-performing sectors. Capitals paired those gains with more significant job expansions—even in less productive services that thrive near affluent urban centers. That’s why a capital’s growth can occur alongside stagnant performance in other metro areas: demand often radiates locally, not nationally. When policy directs grants and resources to a single metro area, it amplifies these effects. When procurement, flagship projects, and research budgets are in place, the employment cycle speeds up. The result is urban over-centralization that is planned, not accidental.

Japan serves as a high-stakes example. For a decade, governments have sought to reduce Tokyo’s dominance through "regional revitalization" efforts, tax incentives, and the relocation of agencies, most notably the relocation of the Cultural Affairs Agency to Kyoto. Still, Tokyo’s networks, finance, and universities have proven to be more potent than these one-time moves. Even the recent rise in remote and hybrid work has centered on Tokyo, not smaller cities, and has not diminished the metro’s importance for knowledge-based tasks. In essence, efforts to decentralize merely shift agencies without creating lasting jobs, budgets, or admissions slots, and rarely have a significant impact. The capital continues to grow because the job market there is robust, mentors are available, and new contracts are easily accessible.

Latin America reveals the politics and economics behind the numbers. Classic agglomeration theory says high-value services, suppliers, and protected markets coalesce in big cities. Mexico City’s GDP share is more than its size; it reflects decision-making—where ministries function, banks lend, and media operate. Lima is now closely tied to national logistics and services, so job creation in outlying areas is unstable. Brazil shows that concentration can fall when states like São Paulo decentralize industries. Yet, finance and elite services usually remain concentrated even as manufacturing spreads. This does not mean workers in smaller cities are less productive. Instead, it is about who sets priorities, hires large numbers of people, and issues labor-recognized certifications.

What a jobs-first deconcentration of urban over-centralization would actually do

First, create job demand—instead of just moving offices. Moving an agency is symbolic. Shifting its procurement, grant-making, and internship processes changes local job markets. EU findings show jobs in related services follow sectoral anchors in capitals. The answer: establish new anchors elsewhere. Direct whole-program budgets—not just small offices—to second cities and university regions, requiring hiring and spending targets for those areas. Set these goals for multiple years in partnership with locals. Assign clean-tech to Cork and Porto, defense AI pilots to Ostrava, and maritime tech to Split. Each should provide scholarships, apprenticeships, and local decision-making power. If so, “less productive services” serving high-income clients will develop on their own.

Second, support talent development where jobs are expected to grow. Capitals thrive because their educational institutions and research facilities are located near recruiters. When students can study, intern, and be hired without relocating, regional retention improves. The policy approach is straightforward: establish co-located applied programs with guaranteed paid job placements. For educators, this means updating curricula in collaboration with employers to offer short, stackable credentials focused on local needs—such as green maintenance for social housing in Wrocław, bioprocess technician training in Thessaloniki, and data operations for supply chains in Katowice. For administrators, alignment of class schedules, micro-credential offerings, and credit recognition is essential to help working students balance campus and employment. For policymakers, it’s necessary to institute “placement-to-budget” rules. If a funded program fails to place 70% of its graduates locally within 12 months, its budget is transferred to a region that can set them. The aim is to ensure that demand aligns with local supply, not just in the capital.

Third, adjust the early-career risk calculation. Graduates gravitate toward dense job markets because they reduce the risk associated with job searching. The government can provide similar support. Offer transferable income insurance for two years to graduates who begin their careers in specific regional hubs. Combine this with relocation vouchers and child-care credits. Require public contracts to utilize dispersed teams: bids should earn higher scores if at least 30% of labor hours are completed outside capitals, verified through payroll data. Importantly, mandate that public companies disclose their headcounts and wage expenditures at the city level. Transparency allows local investors and mayors to negotiate for jobs based on reliable data, rather than assumptions.

Finally, improve transportation and digital infrastructure that currently reinforce urban over-centralization. Capitals benefit from dense job markets partly because connecting workers is straightforward. To replicate this density, we need to minimize time, not just distance. High-frequency, two-way rail service within an hour can connect smaller cities and unite multiple thin job markets into a single strong market without requiring mass migration. The same principle applies online: invest in regional computing resources and regulated data management housed in local universities to allow cloud-based companies to conduct time-sensitive tasks outside capital cities. When data hubs are in towns like Bologna or Brno, jobs will follow.

Some argue that people follow lifestyle choices rather than jobs. If that were the case, the Alps would be a tech hub. In reality, graduates move where job searches are efficient and trustworthy, mentors are readily available, and there are opportunities for second chances if their first job does not work out. This explains why Mexico City’s GDP share remains steady, why Lima holds its ground, and why Tokyo continues to grow. Build strong job markets in the next ring of cities, and the "lifestyle" narrative will thrive there too.

The governance test for urban over-centralization in education and beyond

Educators play a crucial role. Degrees leading to job fairs in capital cities widen the divide between urban and rural areas. Programs that redirect the internship pipeline can help close this gap. University leaders can start with three key actions. First, set aside a specific portion of capstone projects for businesses in designated hubs and mandate on-site weeks for students. Second, collaborate with local companies to co-develop curricula focused on projects funded by national or EU grants, such as retrofitting public buildings or modernizing supply chains for regional small and medium-sized enterprises. Third, publish results at the program level: track where graduates live and work at 12 and 36 months, including their cities, salary ranges, and sectors. When these results improve, regional mayors will have the leverage to push for more cohorts and resources.

Administrators can adjust academic schedules to suit working adults in smaller areas. Organize classes in two- or three-day blocks to allow commuting students to hold jobs. Normalize stackable micro-credentials to enable working learners in smaller cities to build their records without relocating. Treat research grants as tools for job creation by mandating that funded projects hire locally at living wages. Capital-focused systems often do not need to question whether there is a connection between education and employment; they depend on it. In less central areas, that bridge needs to be constructed.

Policymakers should create rules that influence job numbers. They should attach local placement requirements to funded groups in teaching, nursing, and engineering. These fields are essential for every region. Fund regional fellowship years with income support and housing vouchers to lower early-career risks. Establish a “metro choice” in procurement scoring so that bids earn points for spreading labor hours across specific hubs. Require large, publicly funded projects to base their leadership and data infrastructure in those hubs. Additionally, give compacts control over parts of admissions to match talent with the jobs being funded.

Bring the jobs, and productivity will follow

When one metro area contains half of the nation’s population and half its GDP, it shows more than just “natural efficiency.” The EU evidence supports this: productivity in non-metro areas is not declining; what is lacking is headcount and hiring. Japan’s experience indicates that symbols do not achieve much; relocating resources and budgets is crucial. Latin America’s major metro areas remind us that decision-making powers and key institutions are the real driving force. Urban over-centralization is a governance decision we can change. Move demand, not just offices. Build strong labor markets in the next ring of cities by shifting missions, funding, and admissions to places where we want families to settle. Educators can support this shift by aligning curricula and placements with those missions. Administrators can publish local results that ensure accountability. Policymakers can establish rules that encourage distributed hiring. Do all three, and the jobs will come, along with the productivity that capital cities have long claimed as their exclusive advantage.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Capello, R., & Rodríguez-Pose, A. (2025). Europe’s quest for global economic relevance: On the productivity paradox and the Draghi report. Scienze Regionali.

Combes, P.-P., Duranton, G., & Gobillon, H. (2015). The economics of agglomeration.

Dijkstra, L., Kompil, M., & Proietti, P. (2025). Capital cities lead, while other cities lag in the EU. VoxEU/CEPR, 7 Dec 2025.

IBGE (2023). GDP of municipalities shows lower concentration of national economy in 2021. News release, 15 Dec 2023.

INEI / PerúCámaras (2024–2025). Lima’s share of Peru’s GDP (approx. 43–44%). PerúCámaras Informe Económico, citing INEI departmental GDP.

Japan Forward (2023). Cultural Affairs Agency move revitalizes Kyoto. 30 Mar 2023.

KOSIS / Ministry of the Interior & Safety (2024). 2023 Census highlights: Capital Area population 50.7%.

Mexico City Government (2023). Mexico City Economic Review: 17.7% of national GDP (INEGI).

OECD (2018). Regions and Cities at a Glance – Japan: Metropolitan areas produce 74% of GDP; Tokyo’s outsized growth contribution.

OECD (2024). EU regional Social Progress Index 2.0 (capital regions outperform on opportunity). Working paper.

OECD (2025). Shrinking Smartly and Sustainably in Korea (over half of population and ~53% of GDP in capital region).

Republic of Korea (2024). Preliminary results of regional income in 2023 (Seoul Capital Area GRDP = 52.3% of national). Ministry of the Interior & Safety.

RIETI (2023). What to do about rural economies: correcting Tokyo overconcentration. 13 Sep 2023.

World Bank (Krugman, 1993). Urban concentration. Policy Research Working Paper.

Comment